By Don McLeese

There are no losers here.

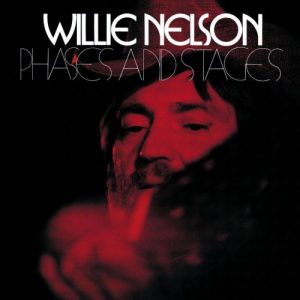

From the start, even before I knew who the 64 slotted contenders were, my critical pick to emerge atop Lone Star Music’s “’70s Texas Progressive Country/Honky-Tonk Heroes Shotgun Showdown” was Willie Nelson’s Phases & Stages. Seemed simple enough Willie was the rock upon whom this unholy congregation of ropers and dopers, rednecks and longhairs, was built. Phases and Stages is his best album. Case closed.

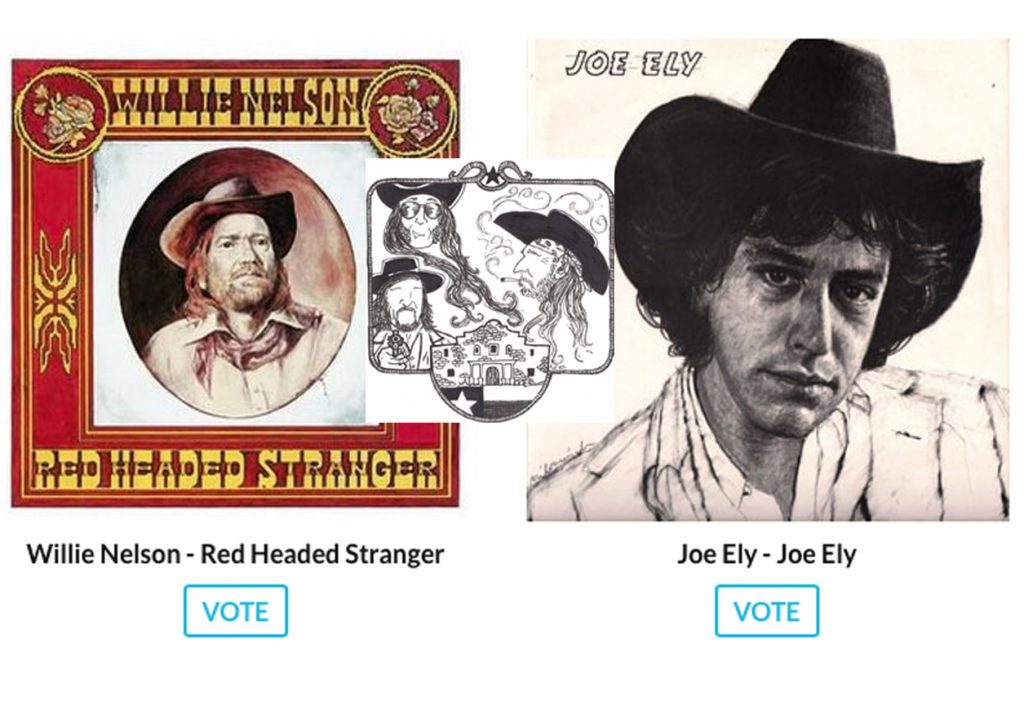

But a critical pick is not a popular prediction, and I figured the consensus would form around Willie’s next album, his mainstream breakthrough, Red Headed Stranger. For those of my generation who were not primarily country fans, that album’s “Blue Eyes Crying in the Rain” was the first Willie Nelson song we knew.

We didn’t know initially that it wasn’t a Willie Nelson song, but one written by Fred Rose and recorded by Roy Acuff almost 30 years before Willie reclaimed in in 1975. And we didn’t realize that we already knew some Nelson songs — “Hello Walls,” “Night Life,” “Crazy” — without knowing they were Nelson’s.

Readers picked Joe Ely’s 1977 self-titled debut over Willie Nelson’s “Red Headed Stranger” in the final round of voting during LSM’s “That ’70s Texas Progressive Country/Honky-Tonk Heroes Shotgun Showdown.”

So, Willie, sure; and Red Headed Stranger, fine. But my final vote actually went to Joe Ely, since I figured that Willie’s popular milestone wouldn’t need my support against what had been a little-heralded debut upon release. And now to see that debut win the whole shebang after beating the Guy Clark album that had just recently beaten Ely’s much stronger follow-up, Honky Tonk Masquerade — well, that defies analysis.

I’d suspect that the fix was in, but that would make the fixer the guy who I depend on to send me a check for this piece. So let’s presume that the elimination of the superior Ely album spurred a rallying of the faithful for his remaining contender, and maybe a little cyber-ballot-stuffing.

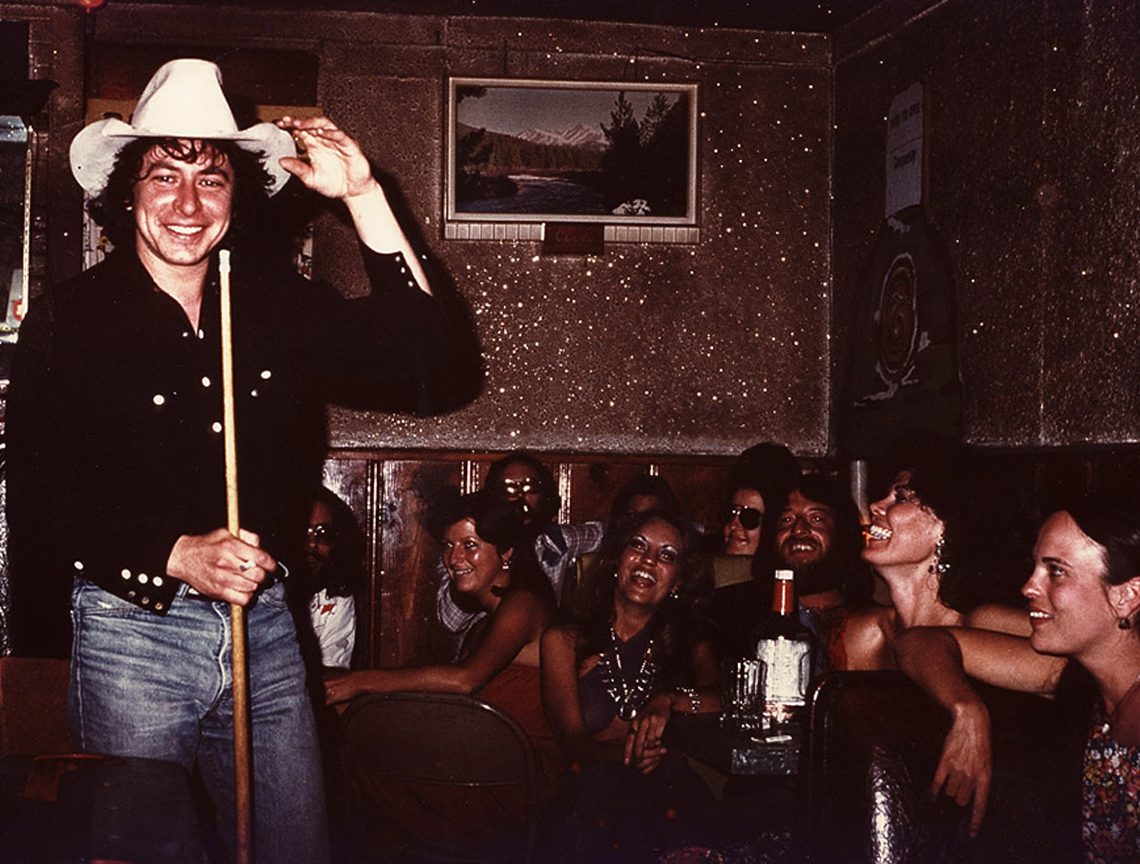

Again, fine by me. Joe Ely, his albums and his band (particularly his two great bands, the earlier Lubbock one and the later Austin one) encompass pretty much everything I love about Texas music, and about this era of Texas music in particular. It would be only a slight overstatement to claim that I moved from my native Chicago to Austin in 1990 because of Joe Ely’s music.

If I were to make this a holy trinity, I’d add Doug Sahm to the litany with Willie and Joe. And I would have been just as fine if a real long shot had won — The Return of Doug Saldana, Sahm’s homecoming release, his return from psychedelic San Francisco with the Quintet and his embrace of his Texas roots as a solo artist. That album, I think, is Doug’s Phases and Stages, his best, though others would generate more attention and sales.

Back to our winner: Joe Ely came out of nowhere (well, Lubbock) in 1977 to announce the arrival of not only a vital new artist but one who came with a fascinating back story that was far from the run of the Nashville mill. He’d brought with him songs from his days with the Flatlanders, written by Butch Hancock or Jimmie Dale Gilmore, and stalwart Hub City musicians such as guitarist Jesse Taylor and screaming steel virtuoso Lloyd Maines, who had honed their interplay at the Cotton Club and West Texas dancehalls.

So, yeah, it’s a really significant release, one that started drawing attention to the whole Lubbock dynamic in a way that nobody had since Buddy Holly, and which established a bond between what Buddy had done and what Joe was doing. That it was considered by MCA Records to be country music was as plain as the cowboy hat atop Joe’s cover shot. And the fact that the label had little hope of finding a slot for this music on the tightly-slotted country charts was also as plain as the album’s plain black-and-white packaging.

In the pivotal year of 1977, when punk, disco, outlaw and other competing strains were all clamoring for public attention, it’s little wonder that a barely promoted debut went all but unheard outside Texas. And when you revisit the album in light of what Joe would accomplish later, it’s easy to see it for what it is — an uneven rookie effort filled with some strong songs that suffered from studio over-arrangement (the mariachi horns and castanets on Butch’s “She Never Spoke Spanish to Me”) and a host of session musician credits.

If you look back to Joe’s days with the Flatlanders (who were unknown then, outside Lubbock and briefly Kerrville and Austin), his emergence as a major-label recording artist in itself was revelatory. In that folkie, hippie band that was never quite a band, Jimmie was plainly considered the best singer and Butch the best songwriter. Joe was the kid sidekick to those slightly older friends.

But Joe also proved to be the one with the most rock ’n’ roll drive, edge and ambition. He was the one with the electrified vision. He was bringing the songwriting of his friends with him, but he and his musicians were adding muscle to the music it had never possessed with the Flatlanders. His was music of the honky-tonk, the roadhouse, where the Flatlanders were more suitable for coffeehouses and folk festivals.

Where Joe Ely was the launching pad — for the artist, his songwriting buddies, his fellow Lubbock musicians — the following year’s Honky Tonk Masquerade was the rocket. The arrangements and musicians were pretty much pared down to Joe’s working band — with the critical addition of Ponty Bone on accordion — and the song selection was even stronger and more consistent than on the debut.

The difference between Joe and, say, the aforementioned Doug Sahm, was that the latter incorporated so many different indigenous strains into his music that he could never cover them all on a single album. Couldn’t, or didn’t. Joe’s achievement is that he did, and never better than on Honky Tonk Masquerade.

Here you can hear the common denominator for Bob Wills’ swing, T-Bone Walker blues, border conjunto, classic country honky-tonk (it just doesn’t get much much more classic than the closing cover of Hank Williams’ “Honky Tonkin’”), Buddy Holly’s seminal rock ’n’ roll and an unbridled energy that converged punk-rock and roots-rock. The showdown that Joe’s debut recently won puts all of this under the “progressive country” umbrella, but this music is hardly country in the way that country fans describe it, and however progressive it is, its musical roots are deep and wide.

On Ely’s second album, you can hear Maines and Jesse Taylor in particular develop that supercharged dynamism that would take, say, “Boxcars,” to a musical place that writer Butch Hancock had never visited. Joe also elevated his own songwriting, with “Because of the Wind” every bit as strong as the best of his Lubbock buddies, and the opening “Cornbread Moon,” shifting into and out of its shuffle time signature, as ebullient as Buddy Holly’s “Oh Boy.”

This was the album that turned heads and opened ears well beyond Texas, that started folks asking how a place as conservative as Lubbock could generate such a radically creative strain of music. And this was the band and the music that would lead both the Clash and Bruce Springsteen to embrace Ely as a kindred spirit. As a live act, the Joe Ely Band was right there with them. And if Joe never quite ascended to that next level of mainstream impact, he’s fully deserving of winning this little showdown, even if it’s with the wrong album.

Speaking of which, let’s switch to the runner-up, Red Headed Stranger, the multiplatinum popular breakthrough that showed that Willie Nelson no longer belonged just to Texas, or just to country music. Where Willie’s legacy from the Armadillo had long been the roper-doper convergence, this was the album that owed little to either the outlaw country favored by the one or the weed-smoking hippie country of the other. This was the album that grandparents and grandkids could embrace, the one that made Willie into an all-American icon, the one that led to his embrace of the Great American Songbook with Stardust.

It’s also the third great and revelatory concept album recorded by Nelson for three different labels over the space of four years. And therein lies a story. The first was 1971’s Yesterday’s Wine, which found him returning to a Nashville studio after returning to his native Texas, and it was the beginning of the end for him as an RCA Nashville recording artist.

Though often given short shrift in light of what was to come, it’s an ambitious and daring song cycle, one that has the initial recording of “Me and Paul” and a revival of “Family Bible” as well as the title track. The album failed to chart and Willie announced his retirement from music because what he considered some of his best work had received no label support. He slunk back to Texas to grow his hair even longer and smoke prodigious amounts of marijuana.

In light of what was happening in Austin, Jerry Wexler subsequently swooped down to reposition Willie for Atlantic Records as a Texas country artist, the flagship signing for the country division of a label better known for R&B and British arena-rock. The label put its big promotional push into 1973’s Shotgun Willie, recorded in New York with a cast of dozens (including Doug Sahm, another recent Atlantic signee), and some strong material, including live performance perennials “Whiskey River” and “Stay All Night (Stay a Little Longer)” and a couple tunes by Leon Russell.

Despite some rave reviews and a lot of promotion, the album was a commercial disappointment for Atlantic, which thus had lower expectations for his second and final album for the label. Producer Wexler and Nelson recorded Phases and Stages with the great Muscle Shoals rhythm section, and all songs written by Nelson — the account of a divorce (Willie’s recent one had been one of the deciding factors in his return from Nashville to Texas), with the first side illuminating the woman’s perspective and the second side the man’s.

It remains the best album Nelson has ever recorded and perhaps the best concept album ever recorded by anyone. Each of these sides has its own emotional arc, with the woman’s renewal away from the husband showing a profound empathy by the artist, complemented on side two by the man’s somewhat bitter acceptance. Though every song advances the narrative, each can stand on its own with Nelson’s best — with the second side’s progression from “Bloody Mary Morning” through “I Still Can’t Believe You’re Gone” and “It’s Not Supposed to Be That Way” particularly powerful, stunning, even devastating in the way Willie phrases his vocal performance. “But be careful what you’re dreamin’,” the estranged husband warns the wife in the last of these. “Soon your dreams will be dreamin’ you.” Has Willie ever written a better couplet? Has anyone?

The freedom that had been granted Nelson to make something this great had great repercussions. Atlantic closed its country division after the album stiffed, and Wexler quit Atlantic in protest. Willie moved to Columbia, where he made his debut with Red Headed Stranger the following year.

Right place, right time, right label? Hard to figure. Columbia succeeded with Willie where Atlantic had failed, at least commercially. Just as Atlantic and Wexler had so recently succeeded with Aretha Franklin — in that same Muscle Shoals studio with those same musicians as Phases and Stages — after Columbia had struggled with her.

As for Red Headed Stranger, this concept album was every bit as daring as its predecessors, and was feared to be as uncommercial by Nelson’s new label, which reportedly thought it was a demo when he brought it to Columbia. But the label had granted Nelson full artistic control, and he fully exercised it.

It remains a signature achievement, its skeletal arrangements highlighting Willie’s guitar, Mickey Raphael’s harmonica (what was he, 12, when they recorded this?) and sister Bobbie Nelson’s piano. It’s as timeless as a classic country waltz and as eternal as a classic murder ballad — the intertwined strains of conceptual ingenuity. And it had its calling card with a hit single, the revival of “Blue Eyes Crying in the Rain,” so spare and pure it sounded like nothing else on the country charts, which it conquered, and then crossed over to establish Willie in the popular mainstream.

With the first chart-topping, multiplatinum album of his veteran career, the image on the cover became his image, and the narrative formed the backbone at the time of his live performance, though most of it has long since been gone from the repertoire (except for the hit and Bobbie Nelson’s “Down Yonder” solo piano spotlight). Though Willie wrote little of the material, his achievement lies in connecting these disparate songs into a coherent narrative, with his “Time of the Preacher” an indelible cohesive. Yet compared with Phases and Stages, Nelson’s artistic achievement here seems a little thin, without nearly as much meat on its bones.

Not that it matters, but if anyone had asked me to rank these albums in order, this would be my ballot:

- Phases and Stages, Willie Nelson

- Honky Tonk Masquerade, Joe Ely

- Red Headed Stranger, Willie Nelson

- Joe Ely, Joe Ely

But the voters have cyber-spoken, and if there’s any worth at all to an exercise such as this, it’s turning listeners on to great albums they might not have heard before, or allowing us to revisit music that perhaps we haven’t heard in decades. And forcing some of us who reflect on these matters to think long and hard on what we most value. During the ’70s, in the state of Texas, music experienced a seismic change, one beyond category or conventional demographics. And we’re still experiencing the aftershocks.

Spot on. Phases is a masterpiece. Honey Tonkin masquerade is as well. I think Jerry Jeff belongs in this group.

Would you please write about Steve Young the “Renegade Picker”. He wasn’t fromTexas but he was one of the original “Outlaw” singer / songwriters who, unfortunately, died earlier this year.