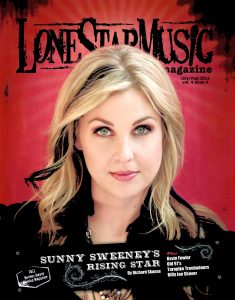

By Richard Skanse

(LSM July/Aug 2011/vol. 4 – Issue 4)

Sometimes, she forgets …

Not, of course, when she’s on — as in onstage, on tour, on the radio promoting a single, onsite for a video or photo shoot, or anywhere else she’s expected to be the center of attention. That, after all, is her job, and Sunny Sweeney, with the pride of a stubborn scrapper who can testify to the satisfaction of busting ass to prove oneself, does not phone things in on the clock.

But find her in the domestic wild — say, at the grocery store, or enjoying a casual dinner with her boyfriend at a chain restaurant — and Sweeney is still enough of a rookie to be caught off guard.

“The other day we were eating at Chili’s, and I was like, ‘Why is that guy staring at me?’ Just to myself, you know?” Sweeney says. “But I kept noticing him, and finally I said to my boyfriend, ‘Why is that guy staring at me?’ And he goes, ‘He’s probably a fan.’ And I went, ‘Oh.’ Like, that didn’t even dawn on me. All I could think was, ‘Am I eating weird or something?’”

It’s not that Sweeney is naïve, or in any way a reluctant rising star. She’s just still in the process of getting fully acclimated to the big picture of it all, having managed thus far in her country music career to focus primarily on only the most tangible aspects of success — namely, keeping her performing and songwriting chops in good enough shape to make a decent enough living to stave off a desk job. She knows, of course, that such success as a public entertainer invariably brings with it a certain degree of celebrity, and she likes to think that she’s level-headed and grounded enough to deal with all that in stride when the time comes. But the telltale signs that it’s already started to creep up on her are still novel enough to just seem, well, weird. She admits that she gets a kick out of hearing gradeschool kids in her neighborhood charmingly calling her “Miss Sweeney!” and serenading her with her song “From a Table Away,” but hearing two dudes talking about her from a table away in Chipotle can make for one very awkward burrito experience.

In theory, maybe fame is easier to process when it hits all at once, in the flick-of-the-switch, overnight fashion engineered for American Idols and Nashville Stars. Doubtless that fast track comes with its own bag of peculiar neurosis, but there’s something’s to be said for jumping (or even being pushed) right into the deep end, just to get that initial shock to the system over and done with all at once. By contrast, Sweeney’s taken a more cautious, wade-in-from-the-shallow-end approach. It’s been seven long years since she first got her toes wet, playing in some of the most gloriously inglorious dive bars to ever cling to the underbelly of the Live Music Capital of the World, and five since she self-released her debut album, Heartbreaker’s Hall of Fame. She landed on Nashville’s radar soon after, eventually finding her way to both the Grand Ole Opry and, with the fall 2010 release of her first national single, “From a Table Away,” the country music mainstream. The song would spend a marathon 36 weeks on the Billboard country chart, peaking at No. 10 in March to give Sweeney the highest-charting debut single by a female country artist since Taylor Swift in 2007. The follow-up, “Staying’s Worse Than Leaving,” debuted at No. 48 in late May, a week before she hit the road on a summer tour opening for superstar Brad Paisley. That puts her in the pool about up to waist deep, but come Aug. 23, when Republic Nashville releases Concrete, her sophomore album and first national release on a major label, Sweeney will be all in — with a better-than-average shot at bona fide country music stardom.

Right now, though, she’s still slowly adjusting to the bizarro-world reality of being kinda-sorta-almost famous. Maybe not quite hounded-by-paparazzi famous, but enough so not to fall out of her chair or freak out in the check-out line every time she sees her name in Country Weekly or even her picture in People magazine. Likewise, she’s learned to accept the fact that along with having her photo taken at award shows, when she’s all dolled-up for the red carpet, there’s going to be more than a few bleary-eyed candid snapshots of her by fans that, given her druthers, would never escape the camera-phone delete button. She figured out a while back that it’s best to check her guitar at the airport, rather than draw extra attention to her sweatpants-and-glasses-wearing self by lugging it through the terminal when she’s got a 5 a.m. flight — but the bold black stripes she wears in her blonde hair still invariably give her away. Even when she’s at her grubbiest and most unprepared, though, she doesn’t have the heart to decline when people request a photo with her. “I just feel like it’d be rude to say no, because it is flattering,” she concedes. “Plus, I signed up for that. But still … I mean, I’ve got my glasses on and no makeup, you know?”

She rolls her eyes a little and shakes her head, but the truth is, Sweeney knows full well why she obliges every fan in such moments, and even why she still feels so genuinely taken aback any time a young girl gushingly tells her after a show that she’s her new favorite artist. That’s because Sweeney knows firsthand what it’s like to be one of those fans, to be that girl trying to keep her cool in the presence of a star. Hell, she already had a few Grand Ole Opry appearances under her belt the first time she met Vince Gill, and she still nearly hyperventilated. “I can meet anybody and at least be able to talk to them, but I could not say anything to him except, heh heh heh,” she says. “I was like, ‘I have a heartbeat in my throat.’ I said that to him. I was so stupid. And the whole time my manager was standing there watching me with his mouth open, aghast.”

She calls that her worst personal “gherm” (geeky fan) moment — well, maybe her worst after the Natalie Maines Incident. About 10 years ago, a few years before the notion of pursuing her own music career had even crossed her mind, Sweeney chanced upon the Austin address of Maines and, on a whim, sent the singer an invitation to her upcoming wedding. Not that Sweeney (who has since divorced) actually knew Maines, or had ever even met her, but she was, you know, a “huge Dixie Chicks fan.” Maines ended up being a no-show, but she did return the RSVP card with the note, “Mr. and Mrs. Adrian Pasdar will not be at your wedding.”

“I still have it,” Sweeney admits a little sheepishly. About a year later, she mustered the courage to approach the Dixie Chick in person when she spotted her at a Terri Hendrix concert featuring Natalie’s father, Lloyd Maines. Sweeney had only barely squeaked her own name out in introduction when Maines looked her over, cocked an eyebrow and nodded in recognition. “How was the wedding?” she asked.

Today, Sweeney can only shake her head and laugh. “I actually don’t ever want to meet her again, because she probably thinks I’m psycho,” she groans. “I am so embarrassed I did that. But it is really funny. And that’s why, anytime someone comes up to me after a show and goes, ‘Oh my God I’m so nervous to meet you,’ I’m like, ‘Nervous? To meet me? Why? I should be nervous to meet you!’ And after I say that, they’re cool and relax. But I still really can’t grasp the fact that people actually think of me like that. It just doesn’t register with me. I’m like, are they bullshitting me? Because I mean, all I can think is … little old me?”

***

The day before our interview, originally scheduled for around noon at an Austin taco joint, Sweeney texts and asks if we can instead do it at her house a little south of town, which will be easier for both of us. Coming off an exceptionally long weekend on the road, the last thing she wants to do is brave Monday morning and lunch hour traffic on I-35. And though she’s cleared her day for our meeting and promises as much time as needed, would it be OK to start at 10 a.m.? She promises loads of coffee. “I’ll be up by 8 or 9,” she insists.

That sounds awfully early for a musician, and seems even more dubious when, later that Sunday night, her name pops up in a Twitter post by Kevin Fowler: “Doing beer bongs with Sunny Sweeney aka @gettingsweenered at my bday party. I’m too old for this.” The linked photo of Fowler and Sweeney doing just that suggests another bad Hangover sequel in the making. But by the time I show up the next morning with breakfast Taquitos from Whataburger, Sweeney appears bright-eyed and none the worse for wear. As promised, there’s fresh coffee on, but she’s already had her own fill of caffeine for the morning and in fact seems to have been up for hours — perhaps having even already knocked out her dreaded daily treadmill session. It’s a discipline she sticks to even on her busiest, sometimes 21-hour work days on the road, when squeezing in even the quickest of workouts can make a world of difference in her energy level come show time. Or even the morning after a little good-old-fashion hell raising with Mr. Beer, Bait and Ammo.

“When me and Kevin get together, we let our redneck flags fly,” she admits with a mischievous cackle. “So last night, they busted out that thing, and Kevin goes, ‘Get over here and do this beer bong with me!’ I said, ‘Hell no, I’m not doing a beer bong — I’m not 16.’ He goes, ‘Well, how old are you?’ I said, ‘18,’ and he’s like, ‘You can still do it at 18!’”

Go ahead and make that 34 — but who’s counting? Truth be told, the guzzling of beer out of a rubber house is a patently ridiculous activity at any age; but on the big-picture scale of seemingly insensible and possibly alarming decisions that Sweeney’s made in her adult life, beer bonging with Fowler is nothing compared to the time she decided, out of the blue at 25, to find herself a living playing country music. Never mind the fact that she had never played guitar, fronted a band or written a song — she could figure all that stuff out on the go. The idea didn’t make a whole lot of sense to her concerned friends and family at the time, but Sweeney’s determination, after working through her own wishy-washy period of second doubts, was ultimately as unshakable as humorist Kinky Friedman’s own famously long-shot bid for Texas governor. Indeed, “why the hell not?”

In answer, Friedman’s gambit proved a bust. Sweeney’s fared rather better, her story thus far seeming to have played out right in sync with the manifest-your-dreams-into-reality-through-the-power-of-positive-thought teachings of The Secret. Of course the real “secret” to Sweeney’s success has had a lot more to do with elbow grease and effort than new-agey wish fulfillment, but she still marvels at the fact that she’s actually pulling it off. Scrolling through the hundreds of gig photos archived in her iPhoto library, most of them from long before she ever made the charts, her mind reels. In 9 out of 10 shots she’s wearing a different Merle Haggard T-shirt; at last count, the certifiable Hagg-fan had 41 of them — though most are now in storage because they’re too big for her. “I’m not going to complain about that,” she says. Clicking on photo after photo, she groans everytime she thinks she looks fat, sighs with nostalgic affection when she sees her trusty old bedazzled tip jar, and laughs at every marquee with her name spelled wrong (her favorite’s from Ginny’s Little Longhorn, on the night of her Heartbreaker’s Hall of Fame CD release).

“I’m glad that I have all this stuff, because it keeps me grounded,” she says. “But it’s hard for me to believe that it’s all fit into the last few years. In September, it will be seven years that I’ve been doing this full time. Sometimes it seems like the days have just flown by. And other days I’m like, ‘Seven years? There’s no way it’s only been seven years.’”

It’s a bit of a stretch, perhaps, but Sweeney’s very first experience singing a country song onstage was actually way back in high school, in the small East Texas city of Longview. By her senior year, Sweeney had participated in theater, speech, yearbook and the soccer team — “everything,” she says, except for choir. But she wanted to be in the senior talent show, which required singing, so she marched into the choir teacher’s room and basically told her to make room. “I auditioned for her without her asking me to,” Sweeney says. “And she was like, ‘Where have you been? Why are you not in choir?’ I said, ‘I don’t have time to be in choir, but I’m going to be in the talent show.’ And she went, ‘OK.’ I sang ‘9 to 5’ by Dolly Parton, and dressed up like her: stuffed my bra, wore a red dress with a belt and put a big wig on.’”

The summer after graduation, Sweeney took a few hours of classes at junior college, but was soon bound for New York, aiming for an acting career but landing in improv comedy. She was a natural, and it scratched her itch to perform onstage, but funny wasn’t covering the rent so she high tailed it back to Texas to reluctantly give school another try. She moved to Austin, but enrolled at Southwest Texas State (now Texas State) 30 miles south in San Marcos. The five-days-a-week commute for her 8-a.m. classes was brutal, as was her masochistic course-load. One semester found her taking 24 hours. “I had to get a special allowance from the dean to take that many hours,” she says. “I’m not a school person, and I wanted to get out as soon as possible. But it’s actually an awesome school, and I ended up with a really good GPA because I actually went and learned as opposed to just partied.”

She graduated in 2001 with a degree in public relations. That skill set would come in handy down the line, but her real musical education at the time came outside of class. One of her closest friends all through college was a fellow P.R. major named Randy Rogers, who moonlighted as an up-and-coming songwriter at San Marcos’ storied Cheatham Street Warehouse.

“I remember my second day at school, Randy — who was known as Randall at the time — walked up and literally, like, smooth-moved in next to me and went, ‘Hey, I’ve got a show tonight,’” Sweeney says. “And I was like, ‘OK.’ He was like, ‘You want to come?’ ‘Not really.’ He goes, ‘C’mon, I’m playing at Cheatham Street …’ Finally I went, ‘OK.’ So my friend and I went to that show, and I remember thinking, ‘Damn, he’s country! Really country — and so good.’ After that we became really good friends, and got the same exact degree, and I started going to all of his shows. We were just friends over music. All I knew back then, and still know, really, is old country, because my parents would teach me about it. But Randy told me about Chris Knight and Guy Clark and Townes Van Zandt and all the other kind of older Texas guys that I had either never heard of or had never really listened to.”

In return, Rogers would mooch rides. “Instead of riding a bus, I would beg her everyday after class to take me home,” Rogers admits with a laugh. “But we both really dug Merle Haggard, and we always talked about and listened to music on the way home. And I was already pimping my band at that point in time, just begging all of my friends to come to Cheatham Street, so I probably drug her out there more times than she wanted to go, but she was always supportive.”

Later, when Rogers was interning at the San Marcos-based music publicity company Propoganda Media, Sweeney landed her own internship (and for a short spell after graduation, a job) in the back of the same office with entrepreneur Chad Raney’s newly launched LoneStarMusic.com, the online Texas music store that would later spawn a physical store in Gruene (along with this magazine). Raney paid cover or arranged guest list credentials for Sweeney to hit the clubs every night so she could promote the website and talk artists into adding their merch to the store. He also had her write the intro to an interview he did with Guy Clark for the website’s first artist Q&A.

“She was really into the music — I remember her just getting so excited,” recalls Raney, who sold his stake in LoneStarMusic in 2009 and now helps small businesses promote themselves via social media buzz as the president of Social Life Marketing of Texas. “But what I remember most about those days working with Sunny is her constant laughing. I can still hear her cackling! At the time, I had no idea and she had no idea that she could or would ever write songs. But I knew she’d been doing some comedy and I knew she was performer, just because of her personality. You know her for five minutes, and you know she’s definitely got the entertainer personality type.”

Sweeney still had a few ordinary jobs ahead of her, though. She got married and moved to College Station, where her husband was finishing up his own degree at A&M, and found work at a newspaper and a waitress gig at the Dixie Chicken. Upon moving back to Austin, she landed a desk job with a child support collection agency. She lasted less than a month before going stir crazy. “I just remember thinking, on my very first day, I can’t do this,” Sweeney says. “After three weeks, I seriously wanted to jump off a bridge.

“All I ever really wanted to be was something in the entertainment business,” she continues. “I didn’t care what I had to do. I thought, ‘Well, I could be an entertainment publicist, or maybe I could work at a booking agency.’ I honestly never really thought about the artist aspect of it, because I didn’t play an instrument, I didn’t know how to do any of that. I remember in seventh grade, my stepdad had tried to get me a guitar and wanted to teach it to me, but I just wanted nothing to do with it at the time. But then I saw this guy playing at a bar one night — this was actually when I was still working with Chad — and I thought, ‘This guy’s getting paid to do this? I could get paid to do that.’ That’s when I went back to my stepdad with my tail tucked between my legs and went, ‘Hey, remember when you asked me if I wanted to learn guitar in the seventh grade?’ He said, ‘Yeah.’ I went, ‘I’m ready!’”

She got her guitar, but the learning curve cooled her engines. When she eventually floated the notion of her playing in a band by a few trusted friends and family members, it was with the cautious hesitation of someone maybe looking to be talked out of it. Some tried to do just that, while others listened to her go back and forth on the matter for so long, they finally said: You can learn. Buckle down already, and just do it.

The latter camp won out. In 2002, she played a handful of quickie amateur spots on the small town Texas opry circuit, and her friend, performer Brigitte London, helped her put a band together in Austin. In January 2003, they played their first and only show together, at a dingy shell of a room in deep South Austin called the Chaparral Lounge.

“A lot of people came out, and it was kind of hilarious, but it was horrible,” she says. “I had every single song written down with all the lyrics on pages in front of me, and I would flip through them. It was all cover songs. I did probably 10 Tanya Tucker songs, a couple of Waylon songs and maybe three or four Merle songs. And it was four hours long. It was the worst gig I ever played in my life.”

It might have been even worse if not for London, who spent the whole night backing her on guitar while desperately trying to correct Sweeney’s rookie mistakes on the fly. Sweeney’s mother, Dee Strickland, remembers it vividly, because she and the rest of the audience could hear every word. “I don’t think Brigitte knew it, but she was on mic, so the audience could hear all of these very strong directions she was giving Sunny,” Strickland recalls. “She was yelling at Sunny the whole way through, just telling her what to do, and I thought, ‘Well, maybe Sunny will make it at this.’ Because Sunny doesn’t usually like for people to tell her directions, and she did every single thing that Brigitte told her throughout the whole show without turning around and griping at all.”

Nevertheless, it would be some time before Sweeney played out again. Her husband’s job necessitated a move to Memphis, and she didn’t play again until their return to Austin in 2004. “For two years I didn’t do anything,” she says. “Literally, not one thing.” Except practice, apparently, because the difference between her 2003 debut at the Chaparral and her return to the stage — at the Carousel Lounge in September 2004 — was night and day. Her set was still mostly covers — primarily classic country, honky-tonk and outlaw fare, with a smattering of Americana — but she’d already started to write, and week by week she got more confident in testing her originals. And there were a lot of shows to test them in, because once Sweeney started playing again, she never stopped.

***

For the better part of the next two years, Sweeney booked herself silly. To this day, it remains a point of pride for her that she hustled so hard, working her publicity skills by day as hard as her performing chops by night. “Nobody can ever say that I didn’t bust my ass, because I played sometimes seven nights a week,” she says. “If I didn’t have my own show, I would sit in with Brennen Leigh or Dale Watson or someone else. But I made myself available to see and meet people and try to get gigs every single day.”

She gives a fond shout-out to Nancy Coplin, who books acts for the Austin-Bergstrom International Airport, for giving her and her band their first paid gig. “We all got $72, plus tips, which was awesome,” she enthuses. “I thought, ‘Oh hell, I’ve made it now! This is the pinnacle!’”

Sweeney’s bread and butter, though, was earned mostly via tips at Austin bars like the Carousel, the Poodle Dog, Ginny’s Little Longhorn Saloon and Ego’s. Ego’s, a tiny, speakeasy-feeling cocktail bar tucked inside a parking garage a block south of downtown, was the closest of the bunch to the heart of Austin’s happening live music scene. The others are all a ways off the hipster-beaten path, neighborhood bars catering mostly to an older, rougher crowd. The first time her stepdad went with her to the Poodle Dog, he took stock of the people loitering in the parking lot and filtering in and out of the door, and told his daughter gravely, “I’m bringing my gun in this bar.”

“I went, ‘The hell you are! I play here all the time. It’s fun!’ And he said, ‘You’re not playing here tonight if I don’t have my gun in my pocket.’” Sweeney rolls her eyes, but admits she saw plenty of action. “I think a lot of the reason that I can control crowds now and keep their attention is because I had to force myself to do that in these bars with drunk old men, where there were fist and knife fights and people with guns. But I mean, I loved the Poodle Dog. I played there almost every single Sunday for two years, and those shows really truly made me part of who I am right now. Some of my most loyal fans are from there. And Ginny’s Little Longhorn, too. I still go to Ginny’s every time I’m home.”

She played outside of the Austin bar and honky-tonk circuit, too. There were hole-in-the-wall joints in other Texas cities and throughout the hill country, along with few trips to Europe and more than a smattering of regional and road shows with some of the bigger acts on the Texas music scene, most notably Fowler, the Randy Rogers Band, Jack Ingram and Jason Boland. “Those four were so freaking supportive of me,” she says. “They would let me open for them, talk me up during their shows, and afterwards they weren’t weird about me being a chick, because they know I can hang.”

Indeed, some of the guys in those bands have even been known to proudly wear their “Sunny Sweeney: Breaking up the Sausage Party” T-shirts onstage. But like just about every other woman artist in Texas, Sweeney’s run up against her unfair share of boys-club prejudice. “I remember Blaine, from Blaine’s Pub in San Angelo, saying, ‘What am I gonna do with a chick playing my bar?’” she says. “He wasn’t the only person that ever told me that, but I was so upset when I got off the phone, I started crying. And then it pissed me off. I called him back and said, ‘You know what you’re going to do with a girl? The same thing you’re gonna do with a guy. When are you giving me a date?” He relented and booked her for a Friday and Saturday night. She had him at “Delta Dawn.” “He said, ‘You can come back any time you by-God want.’

“But I mean, that’s how it’s been from day one,” she continues. “I’ve had to just get in front of people and prove myself. I’ve talked to other girl artists, and they’ve all said the same thing. It is so hard to break into a scene, it can be like beating a dead horse. Some guys assume like, ‘You’re a pretty girl, you should just be able to bat your eyelashes and get a gig.’ Hell no! You’ve got to be able to back it up!”

Sweeney’s debut, Heartbreaker’s Hall of Fame, which she began recording in the fall of 2005, would go a long ways toward doing just that. Produced by guitarist Tommy Dettamore and drummer Tom Lewis, with a co-production credit for Sweeney, the album plays through like 40 minutes of country jukebox heaven. Sweeney’s voice is equal parts honey and hard twang, and her three original songs (including the title track and the standout “Ten Years Pass”) stand tall next to choice cuts by some of Americana and contemporary honky-tonk’s finest: Jim Lauderdale, Iris DeMent, Libbi Bosworth, Keith Sykes, Audrey Auld and even Emily Robison of the Dixie Chicks.

Sweeney’s debut, Heartbreaker’s Hall of Fame, which she began recording in the fall of 2005, would go a long ways toward doing just that. Produced by guitarist Tommy Dettamore and drummer Tom Lewis, with a co-production credit for Sweeney, the album plays through like 40 minutes of country jukebox heaven. Sweeney’s voice is equal parts honey and hard twang, and her three original songs (including the title track and the standout “Ten Years Pass”) stand tall next to choice cuts by some of Americana and contemporary honky-tonk’s finest: Jim Lauderdale, Iris DeMent, Libbi Bosworth, Keith Sykes, Audrey Auld and even Emily Robison of the Dixie Chicks.

“I know a lot of people are like, ‘I would never let anybody hear my first record,’ but I’m proud of mine,” Sweeney says. “I don’t listen to it now because I don’t like hearing my own voice, because it sounds weird. I don’t think I had really found my voice yet at the time, because I didn’t know what the hell I was doing. Thank God Tommy Dettamore was there to coach me through the whole thing. But it’s still the biggest compliment when people, especially other artists, tell me they like it, because nobody told me what kind of record to make. It’s the record I wanted to make.”

Sweeney self released Heartbreaker’s Hall of Fame in March 2006, packing tiny Ginny’s to the rafters for her release party. “There were 300 people there,” she marvels. “My mom counted!” A few months later, a copy of the album, in a blank envelope, landed on the desk of Scott Borchetta, president of Nashville’s Big Machine Records.

“I still to this day don’t know how that original indie CD landed on my desk,” Borchetta says. “But I remember putting it on, and I just fell in love with her voice and her attitude. So I went on MySpace and found her, and sent her a message saying, ‘Hey, I have this little label in Nashville, and if you’re going to be in Nashville any time, let’s visit. I like your record.”

That “little label” happened to be having a very big year, scoring a No. 1 hit with Jack Ingram’s “Wherever You Are” and the smash debut by teenaged wunderkind Taylor Swift. But Borchetta’s name didn’t ring any bells with Sweeney when the message landed in her inbox. “She didn’t get back to me right away,” he chuckles, “but she finally did, and we talked on the phone and then she came to Nashville, and I met with her and her husband at the time and talked about where I thought she was in her career at the time, just from what I’d learned from looking online at the shows she was doing. I told her that more than anything else, she needed to go out and up her game, keep writing, keep working, and that if it would help, I would pick up distribution and she could go back to Texas and tell clubs that she was on Big Machine. Just to help her get leverage back in Texas and improve her situation.”

Big Machine re-released Heartbreaker’s in March of 2007, but only in and around Texas and the South. A few singles (“If I Could,” “Ten Years Pass”) were also serviced to stations in the same region. Conservative, yes, but by design. “Our goal was, let’s see if we can sell 10,000 of these, get her some distribution and exposure where we can, and just build this from the grassroots,” Borchetta explains. “I think that can still be done with an act that has the desire to get out there and do it.”

Meanwhile, Sweeney followed Borchetta’s directive: keep on keeping on, but harder. She began supplementing her regular Austin gigs with more and more touring, along with enough trips to Nashville for songwriting sessions to eventually merit finding an apartment there. It was very much a bittersweet period for her, rife with head-in-the-clouds, pinch-me moments (making her debut on the Grand Ole Opry; recording a cover of “Good Hearted Woman” with Jessi Colter for a Waylon Jennings tribute record) but also heavily weighted with the somber realization that her marriage was coming to an end. But through it all, she just kept on writing, fully aware that when her label was finally ready to release her second record, she was going to be expected to prove herself on a much bigger playing field than ever before. In June of 2009, Borchetta moved her from Big Machine over to Republic Nashville, his new joint venture with Universal Republic (which, in turn, is part of the largest music company in the world, Universal Music Group). Essentially, Sweeney was now a major-label artist; hit or miss, her next release was going nationwide.

It hit. Not overnight, no, but with a steady persistence and unshakable determination worthy of its maker. “I was talking to her the whole time that song was moving up, because they worked it for a long time,” recalls Rogers of Sweeney’s “From a Table Away,” which spent nine months on the charts. “Man, I’d call her every week or so to see where she was at, see where the single was at. And we joked about it, too, because you know I’ve never even had a Top 40 country Billboard song, and now she’s already run one up to No. 10. But I’m so happy for her. I think it’s amazing that somebody from Austin could have that chart success with a song doing their own sort of brand, because when you hear a Sunny song, you know it’s definitely got her stamp on it and it does sound like Texas. I was completely blown away and so happy for her. We all know very well that she deserves to be there.”

It hit. Not overnight, no, but with a steady persistence and unshakable determination worthy of its maker. “I was talking to her the whole time that song was moving up, because they worked it for a long time,” recalls Rogers of Sweeney’s “From a Table Away,” which spent nine months on the charts. “Man, I’d call her every week or so to see where she was at, see where the single was at. And we joked about it, too, because you know I’ve never even had a Top 40 country Billboard song, and now she’s already run one up to No. 10. But I’m so happy for her. I think it’s amazing that somebody from Austin could have that chart success with a song doing their own sort of brand, because when you hear a Sunny song, you know it’s definitely got her stamp on it and it does sound like Texas. I was completely blown away and so happy for her. We all know very well that she deserves to be there.”

Sweeney shares a co-writing credit on the song, a plaintive, lovelorn lament that casts its sympathies with the “other woman,” but says it’s not about her. She did see it happen, though. “A week before that writing session, I saw literally the exact situation in the song happen at a restaurant,” she says. “I mean, I could just tell. I’m very intuitive. That’s how I write a lot of songs. I have so many song ideas from people that don’t even know that they’re giving me a song idea.” Which isn’t to say she’s averse to writing about her own life as well. At least a couple of the songs on the new record were born out of firsthand experiences, including her divorce: “Worn Out Heart” and the second single, “Staying’s Worse Than Leaving.”

“Yes, that’s about me,” she admits. “But I think anybody can relate to it because it never says ‘we’ve been married for this long’ or anything; it’s just about a relationship ending.”

Sweeney co-wrote seven of the 10 songs on the new album, and hand-picked the other three with producer Brett Beavers. Though not without its share of straight-up honky-tonk (including the opening “Drink Myself Single,” which would have fit right in on Heartbreaker’s), it’s a slicker, more contemporary sounding record than her debut. But it’s a much darker and emotionally mature one, too: less twang, more pain. Sweeney named it Concrete to convey a sense of resiliency.

“I just wanted to name it something that was solid,” she says. “I didn’t want it to be called something like Dandelions and Butterflies, because the songs are all tough songs. Whether that means physically tough or emotionally tough, or whatever. Because quite honestly, I haven’t had a perfect life; at least personally, it’s been shitty for the last couple of years. But good songs came out of it. I listen to some of these songs, and I can literally still feel it in my stomach — just, you know, gulp. Going through divorce is the hardest thing I have ever done, and I would never wish it on my enemy. But knowing that I made it through to that other side emotionally — that’s why it’s called Concrete.”

“I just wanted to name it something that was solid,” she says. “I didn’t want it to be called something like Dandelions and Butterflies, because the songs are all tough songs. Whether that means physically tough or emotionally tough, or whatever. Because quite honestly, I haven’t had a perfect life; at least personally, it’s been shitty for the last couple of years. But good songs came out of it. I listen to some of these songs, and I can literally still feel it in my stomach — just, you know, gulp. Going through divorce is the hardest thing I have ever done, and I would never wish it on my enemy. But knowing that I made it through to that other side emotionally — that’s why it’s called Concrete.”

***

The title of her new album may be a metaphor, but the emotional “other side” that Sweeney speaks of is very much real. In the aftermath of her divorce, a longstanding friendship with an Austin police officer she met years ago at Ginny’s Little Longhorn bloomed into love, and she unreservedly calls the new relationship the one she’s been waiting for. “I can say that,” she says, “because I’ve been through enough in the past to know what I do and don’t want, and this is what I want.”

Plus, her mother loves the guy. “My mom told me the other day that she was talking to him on the phone, and she told him, ‘If y’all ever break up, it’s going to be the saddest song that Sunny ever wrote,’” Sweeney says. “And I’m like, ‘Dude, that’s a good song idea!’ She had no idea.”

Maybe not. Dee Strickland admits that she’s never fully understood “the entertainer’s mind.” But she’s as happy seeing her daughter happy in love as she is witnessing her successfully live out her dreams — however much her own maternal instincts worried in the beginning. “Truthfully, I think I thought she’d lost her mind,” Strickland says of her initial reaction to Sunny wanting to “get a band going and sing around town.” “But we supported her, and just thought, ‘That’s her thing, we’ll see how it works out.’ I knew she had talent and thought she would be a great performer of some kind, if she chose to do that, but I was just very surprised to see her select what I thought — correctly, I might add — would be a career that would require such enormous personal sacrifice. In the beginning, like when she was playing at the Carousel the first few times, it was fun. And I think there’s still that for her every time she goes onstage, because she’s always wanted to entertain and she’s always been good at it. But off the stage, it’s so much like a business now that she’s really had to concentrate on treating it like a real job. I don’t know if that’s really a change she’s gone through or not, it’s probably just growth, but she’s a lot more responsible now. Because it’s definitely not all fun and games.”

But Sweeney herself never really thought otherwise. She’s had plenty of fun, and still does, but from the very first time she set out her bedazzled tip jar — later supplemented with a credit card machine to accept tips as well as T-shirt sales from punters carrying only plastic — she’s always treated this as a real job. And it’s a mindset she’s maintained through everything that’s come since, chart hits and burgeoning fame included. “Some people do this to be famous,” she says, “but I’m doing this to be successful, so that I don’t have to ever go back to a desk job. I like doing it, because it’s something I know I’m good at — I’m not an idiot — but I don’t need or want to be the center of attention all the time. But onstage, yes, because as long as I have people’s attention and they’re responding to my music, I know I can sell records and keep doing this. That success is all I want.”

That said, hearing a thousand or more people sing “From a Table Away” back to her is always pretty all right, too. The first time that happened, Sweeney about fell off the stage. “Seriously, I was spazzing,” she says. “As soon as I was done, I went outside and called my boyfriend, crying hysterically, ‘Oh my God, the whole crowd was singing my song!’ It was nuts … and soooo gratifying.”

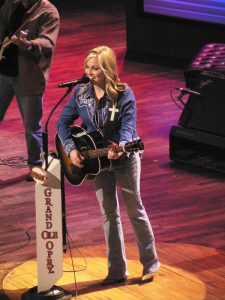

Success and resulting fame aside, moments like that will never get old for her. Nor will playing the Grand Ole Opry — the only show on earth that has ever really given her stage fright.

“Sunny can sing in front of 20,000 people and it doesn’t bother her at all, but she still gets nervous at the Opry,” says Strickland. “No other music venue has ever affected her that way, but she loves the Opry so much, I guess it’s just different. She gets shaky and nervous before and has to write her cheat sheets on her guitar. The first time [March 2007], she kind of couldn’t even sing, because she was mostly screaming, ‘I’m at the Opry! I can’t believe I’m at the Opry!’ between every phrase. Which was kind of embarrassing, because there were like 50 people in our family and friends that went that first time. But we were still proud of her.”

“I did ‘If I Could’ for my one song, and it was the stupidest choice I could have ever done, because it was so fast and I was so nervous, I sang one verse and then cried,” Sweeney says. “I was thinking, ‘Sunny, I hope you enjoyed this, because that’s the last time you’re ever getting invited here.’ So I walked off, still crying, and I saw Pete Fisher, the general manager, and I remember saying, ‘Thank you for letting me play at the Opry, it was so awesome, I can’t believe I cried, I’m so sorry …’ And he goes, ‘Next time, you’ll get more than one song.’ And I went, ‘There’s going to be a next time?!’”

There’s since been 23 more times, and counting. She even got to play at the Grand Ole Opry’s 85th anniversary, an honor in and of itself, for sure, but one that also came with a big honking gift basket. And Sweeney’s favorite prize out of her huge Opry swag bag? An $85 gift certificate to Dollar General. She couldn’t wait to tell her boyfriend.

“I came home the next day and went, ‘Baby, we got an $85 gift card to Dollar General!’” Sweeney says. “And he’s like, ‘Are you serious? Sweet! Let’s go!’ So we go to Dollar General, pushing the basket around and piling it up with laundry soap, toilet brushes, sponges, shampoo, coffee cups and all sorts of other stuff we use at the house. It was Christmas time, so he got a nutcracker dressed like a policeman, too. We got so much crap, the basket was full. And then ‘From a Table Away’ came on over the store music speakers. I’m like, ‘Oh my God, I can’t believe this is happening.’ I called my dad and went, ‘Daddy, we’re going through Dollar General, getting toilet paper and stuff with my gift card from the Opry, and my song just came on …’

“We were just dying laughing,” Sweeney says, laughing still. “It was like everything coming full circle.”

If that ain’t country …

[…] aside, though … the last time I interviewed you was back in 2011 when Concrete came out, so I had to do a little Wikipedia cramming last night to catch up on any news I might have missed […]