By Slaid Cleaves

(LSM May/June 2013/vol. 6 – Issue 3)

I was 9 years old the day I first sat down next to Rod Picott on the school bus. We hit it off right away, two sensitive artist types in a little dairy farm and shoe factory town an hour north of Boston. I recall our first conversation being pretty exotic, considering our location: something about wanting to be actors when we grew up.

We were buddies for a few years, riding our Schwinns to each other’s houses, less than a mile away, playing Beatles records and spinning our Evil Knievel action figures down the driveway. But although we bonded over our shared interests and our low social status in school, we were quite different as well. I was the teacher’s pet and Rod was the rebel. I was precociously bright and eager to learn but not yet able to think critically. Rod was intimidatingly intelligent, small-town stifled, and way ahead of his time. I recall a few years later, as I started sixth grade, I was watching Happy Days and enjoying “Love Will Keep Us Together” on the radio while Rod was into Monty Python and “Born to Run.” This was in 1975 and he was in the fifth grade. He was not only way ahead of the other kids in our school, he was ahead of most of the adults in South Berwick, Maine.

When I moved up to junior high and then high school, we were separated for a time. Rod was just a few months younger than me and in the previous grade. We both struggled mightily during those years, trying to find a place to belong amid the frightening slow-motion storm of puberty. I became painfully shy and unconfident, uncomfortable in my skin. I had thick glasses and braces. I was trying to be “well-rounded” for college, where, my mom kept telling me, things would get better. I took classical piano lessons. I joined the yearbook committee. Math team? Check. But I didn’t feel I belonged anywhere. I didn’t have any close friends. I wasn’t even sure who I was.

When Rod entered Marshwood High School in 1979 I was a sophomore, and on the bleachers of gym class we re-established our friendship. Gangly and uncoordinated, we were invariably the last two picked for teams. We’d often end up on the sidelines together, talking about the mysterious and powerful world of rock ’n’ roll. While I had spent the past few tumultuous years obsessing about my grades, winning science fairs and going to astronomy camp, Rod had been hanging with an older crowd, driving to New York City to see the Clash, dating girls and drinking. He seemed so cool, above the silliness of high school, older and experienced. And yet we still shared this bond of music and childhood friendship.

Rod unknowingly became my mentor and guide into another world as I aspired to become a whole new person, with new interests, new friends, new priorities. I wanted to be respected. I wanted to belong to something I believed in. But mostly, I suppose, I wanted to be noticed by those mysterious, untouchable, tongue-twisting creatures. Within a year I got contact lenses, cut my hair, stopped wearing Toughskins, and traded in my telescope for an electric piano. Rod turned me on to the Ramones and got us tickets to see the Who in 1979, right after the Cincinnati tragedy. Our parents almost didn’t let us go. It was at the Boston Garden, an ironically named, dank, decrepit arena where only mildew would grow. But Pete and the boys poured gasoline on that crowd of disaffected youth and then threw a match that ignited a seething explosion of energy I haven’t felt since. We drove through a snowstorm to see Springsteen’s four-hour show there the next year. My transformation was in full swing. At a college prep summer school adventure I kissed a girl, fell in love. Even as it was happening I thought of 1980 as the year I left childhood and became a “person.”

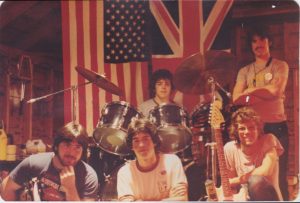

With a couple of other classmates Rod and I formed a band called the Magic Rats. In his father’s garage, much to the dismay of the neighbors, we banged out flat, rudimentary versions of Bob Seeger, J Geils, Tom Petty, and Bruce, our hero of heroes. Over the next year or so we developed a creed that put music ahead of all else in life. As people that age do, we focused in on something that gave meaning to our dull lives, trudging to school on dark frigid mornings, dozing through classes on subjects we thought we’d never need in our unfolding lives. The romance, the drama, the cause to believe in, we found in Springsteen’s and Petty’s songs and personas. Rod and I vowed we would never give up on our band. With naive grandiosity we told each other we would sleep in the street to preserve the dream, and we promised that we would never sell our songs to commercials — despite the fact that we hadn’t even written any of our own songs yet. We worked after school in a G.E. factory in gritty Somersworth, N.H., cleaning bathrooms for two years to raise funds for band equipment. We hung out at Daddy’s Junky Music Store, enthralled by road stories told by the washed-up musicians who worked there. We stole Hood Dairy milk crates from the greasy back alleys of Cumberland Farms convenience stores to make a drum riser. We tried to make stage lights out of old paint cans. I remember drawing stage designs and logos for the Magic Rats on the brown paper bag covers we were all required to make for our school books. Everything we did revolved around our band as we emulated our heroes. With its boardwalk and arcade, York Beach was our Asbury Park. Our matching, rusted-out, hand-me-down wrecks were our “Hemi-powered drones.” We longed to find our “barefoot girls sitting on the hood of a Dodge, drinking warm beer in the soft summer rain.”

Sometime in the winter of 1981, we heard that the Stompers were coming to Durham, N.H., a college town not far away. The Stompers were a popular bar band out of Boston at that time who seemed, to us anyway, poised to join our heroes on the national stage. They had local radio hits and played the kind of yearning, passionate and gritty rock ’n’ roll that thrilled us and promised us a way out of our weak, dull lives. We even played a couple of their songs in the Magic Rats. It doesn’t seem so dramatic now, but in 1981 in a small town in Maine, all we got on the local radio seemed to be Andy Gibb and Air Supply and Christopher Cross. Schmaltz. Live music in our town was nonexistent. We HAD to go see the Stompers. There was only one problem. The show was at a bar, and we were 16.

After much discussion and hand-wringing it became obvious that we had to get fake IDs. Rod quickly procured one that said he was 26 and had an unpronounceable Polish name. He spent some time memorizing his new birth date. Believe it or not, Maine drivers licenses at the time had no picture and no lamination. You just got a piece of thick yellow paper with your info typed onto it. Rod convinced me that we had to alter my newly acquired license. It was the only way. Here’s where the differences between us showed themselves: I was still the goody-two-shoes and Rod the devil on my shoulder (or the Eddie Haskell, at least). After much cajoling and argument and hesitation, I assented. We carefully rubbed out the “4” of 1964 with a pen eraser. Of course it dug into the colored paper pretty obviously. It didn’t look good. We soldiered on though, and carefully drew in a “1” to make me 19, which was old enough at the time. The ink of the ball-point pen blurred into the roughed-up paper. It looked terrible. But we convinced ourselves it was our only hope. “It’ll be dark. They’ll just glance at it.”

We arranged for the use of my parents’ Ford Gran Torino that night, and we piled into that station wagon full of anticipation: Rod, his “barefoot girl” Tracy, and myself. Rod was always one to savor the excitement of an upcoming show. For days, weeks even, he would be counting the days, discussing how great it would be, pumping us up for an unprecedented experience. Little did we know our first hurdle of the night was lurking just around the corner. Not two miles from my house, we passed a local cop at an intersection. We had nothing to be afraid of. We weren’t drinking or doing anything wrong. Except I was driving with a forged license. That little bit of fear when you see a cop flashed through me for the first time. We’re fine. Calm down. But the cop turns to follow us. Then the blue lights come on. Damn!

I’m shaking now. Rod’s cool, though. He keeps me from panicking. He says calmly, “Just tell him you forgot it at home.” Right. Mister head-of-the-class is going to lie to a law enforcement official now. But that’s what I did. The officer asked my name and went back to his car. With amazement, we noticed about that time that Bruce Springsteen’s “Growin’ Up” was playing on the radio. To hear this song on the radio was an extremely rare event in our town in the pre-Born in the U.S.A. era. And to hear it while we were embarking on a clandestine adventure to a forbidden world seemed like a sign. It calmed us down a little, and gave us the feeling we were on a righteous mission. The cop came back with a warning, saying I should have dimmed my high beams at the intersection where we had passed him (a lesson I learned for good on the spot that night), and a request to come down to the station with my license within 48 hours. Then he let us go. Whew!

It was a mixture of great relief, but also apprehension, that I felt as I pulled back onto the road. The incident proved that we didn’t really have faith in my altered license after all, and there was no way I was going to use it to try to get into the show. We headed on to Durham, though, not sure what we would do. Scope out the situation, I guess. See how tight security was. We parked the car then hung around the door for a while, watching people go in. Everyone was getting carded. Damn. I wasn’t about to use my butchered ID. Tracy had been hoping to just waltz in on “Joe Cziembronowics”’ arm, but it was clear that Rod and only Rod had a shot at getting in. He went to the door and they stamped his hand. I don’t think they even carded him; Rod looked a lot older than 16 — he’d already been buying six packs at local convenience stores for a while.

I stayed outside with Tracy. Our brains were spinning. How can we get around this? It’s so unfair. We don’t want to drink. We just want to see the band. A couple of concertgoers asked us what we were doing hanging around the club. When we told them, they were sympathetic. One said we should just rub a little mud on our wrists — to fake a hand-stamp. That sounded pretty far-fetched.

Rod came back a half-hour later when the band was on break, telling us how great it was in there. He wanted me to use his fake ID. But I didn’t look 26. I’m sure I didn’t look a day over 15. We took a look at his hand-stamp and discussed faking our way in. Worth a try, I guess. What can they do? Emboldened by Rod and by our frustration and by that 16-year-old blood that is ready to take some chances, Tracy and I stooped down for some cold, hard mud, and rubbed it into the backs of our wrists in the shape of an X. Then Rod and Tracy and I walked right in, looking straight ahead and holding up our hands with feigned casualness. We made it past the door man and into the bar. Rod led us to a little spot where we squatted down right in front of the stage. I was waiting for the hand on my collar but it didn’t come.

The place was packed, smoky and sweaty and buzzing. Soon the band came out, and there were our heroes, just an arm’s length away, pumping out a righteous, rowdy, romantic rock ’n’ roll. I had been to a few rock concerts before, but only in huge arenas, where the band is hundreds of feet away awash in a light show and the sound is loud but somehow distant. But this was something totally different. We could see and hear and feel everything: the stomp of their boots, the sun-lamp warmth of the lights, the sweat pouring off as the guys put their all into it. Every chiming chord, every drum beat, every shout from the heart was happening just a few feet away. As the music poured through us we made eye contact with the band, just a bunch of guys from down the road, a few years older than us, and we started to believe: This could actually happen. If we keep the faith and work hard, we might be able to do this someday, just like them.

And so a dream is born.

Rod and I did keep the faith. Through many trials and disappointments and setbacks we kept working at our craft while trying to support ourselves however we could. The band broke up. We graduated from high school. We drifted apart and each joined or started new bands for a while. They weren’t good bands, no matter how hard we tried. The romance faded away some, and then some more. Our limitations slowly became evident. But we kept on; a little faith is all you need to keep going on … and a little delusion, maybe. We moved out of Maine, found niches to survive in. I’ve been in Texas 21 years now. Rod’s been in Nashville almost as long. We get together a couple times a year to write, do a run of shows, or just hang out.

One song Rod brought to me in 1998 was almost complete. I just changed a couple of lines and straightened out the melody a little bit. “Broke Down” got played on radio stations across the country, and I got to go out on the road with a tight little combo and play in the lights, just like my heroes. It wasn’t the sweaty exuberant rock ’n’ roll of my youth. It was a more subtle, gentle, literary connection I made on stage. But it felt just as true, just as important. It made me feel like I was doing something worthwhile with my life, and I still feel blessed that I’ve been able to achieve such an improbable dream. A dream forged in a childhood friendship.

You never know who you’ll be sitting next to on the bus.

[…] night I re-read the guest piece you wrote for our magazine, “Growing Up,” about how you met (fellow artist and frequent co-writer) Rod Picott as a kid and started your […]