By Kelly Dearmore

(LSM Oct/Nov 2014/vol. 7 – Issue 5)

The Tradewinds Social Club is not the kind of joint where lasting musical memories are usually made. Located in a less-than-ideal area of the Oak Cliff neighborhood in southernmost Dallas — “on the corner of Carjack and Hold Up,” to borrow directions from one Yelp reviewer — it’s the kind of fabulously down-and-dirty dive bar beloved by blue-collar types and slumming hipsters alike for its cheap beer, stiff drinks, and decidedly glitz- and pretension-free atmosphere. But as a concert venue, suffice it to say that it’s a great place to play pool, darts, and shuffleboard. On the odd night when Tradewinds does feature live music, it invariably feels more like an afterthought than the main event. There’s no stage to speak of; just a side of the room with just enough space for a band to set their gear up on the ragged carpeting and do their thing for whoever cares to listen, leaving plenty of room on the other side of the bar for the Social Club regulars to carry on with their usual drinking, socializing, and pool shooting undisturbed.

The Tradewinds Social Club is not the kind of joint where lasting musical memories are usually made. Located in a less-than-ideal area of the Oak Cliff neighborhood in southernmost Dallas — “on the corner of Carjack and Hold Up,” to borrow directions from one Yelp reviewer — it’s the kind of fabulously down-and-dirty dive bar beloved by blue-collar types and slumming hipsters alike for its cheap beer, stiff drinks, and decidedly glitz- and pretension-free atmosphere. But as a concert venue, suffice it to say that it’s a great place to play pool, darts, and shuffleboard. On the odd night when Tradewinds does feature live music, it invariably feels more like an afterthought than the main event. There’s no stage to speak of; just a side of the room with just enough space for a band to set their gear up on the ragged carpeting and do their thing for whoever cares to listen, leaving plenty of room on the other side of the bar for the Social Club regulars to carry on with their usual drinking, socializing, and pool shooting undisturbed.

But the night of Saturday, Feb. 25, 2012 was an exception.

It didn’t start out that way. For the first half of the night’s double bill, the pool-table side of the bar was a lot more hopping than the music side. To be fair, Buxton — an indie outfit from Houston newly signed at the time to New West Records — did the best they could, all things considered. The band members played with their backs crammed up against the front wall, facing a modest crowd of a couple dozen young fans who were all no doubt Tradewinds first-timers. You could tell as much by the way they listened attentively the whole way through while jammed in close together in a safety-in-numbers sort of way, even leaving a good 10 or 12-foot gap between audience and band. They all looked about as uncomfortable and out of their element as Buxton’s orchestral folk-pop sounded in the room, and as soon as the set was over, most of them began to clear out as quick as they could.

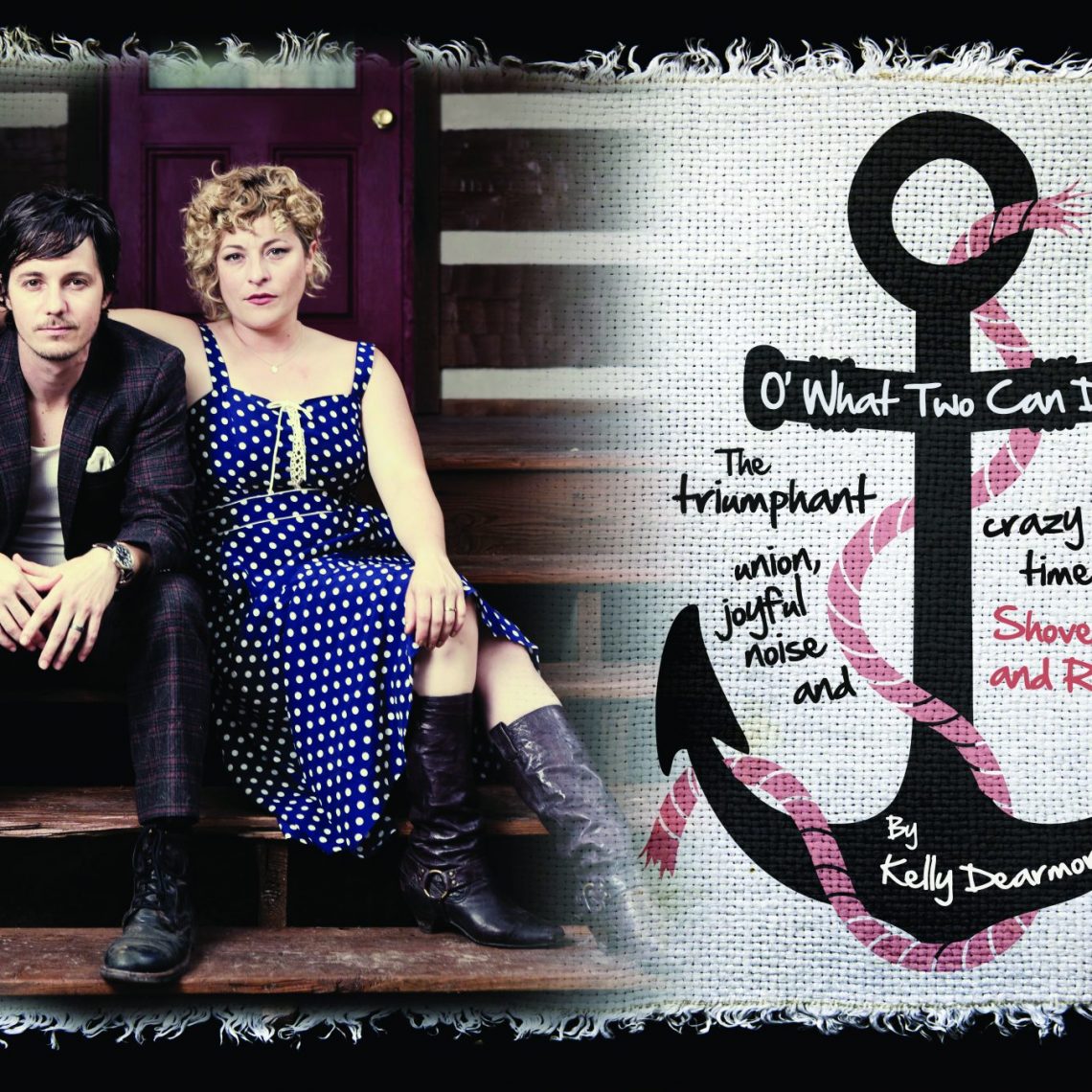

That’s when two outliers who’d watched the whole show from back in a corner — a rail-thin dude in a trucker cap and a lively, grinning gal with a mop of thick auburn curls — stepped out of the shadows and got to work. Buxton was still packing up and hauling out their plethora of instruments as the new duo claimed a spot in practically the middle of the room and set up their own arsenal: two mics, an acoustic guitar and a single snare drum. They punched out a couple of test shouts into their mics, and like the flick of a switch, the atmosphere in the entire bar seemed to change. A new crowd ambled over and formed a tight crescent around the guy and gal and their minimalist set-up, and in marked contrast to Buxton’s polite but overly reserved fans, this lot — an all-together rowdier-looking bunch sporting an impressive array of colorful, sometimes menacing tattoos and even a fair amount of leather — looked primed and ready for something more than just a little show. Fueled by a heady Saturday-night buzz and a palpable charge of pent-up, restless energy, they were ready for release — and Cary Ann Hearst and Michael Trent of Shovels and Rope delivered in spades.

The set started out with Trent on drum (and harmonica) and Hearst on guitar and lead vocal. But over the course of their set they harmonized together and switched roles and instruments as frequently and deftly as their up-tempo songs swerved in and out of country, rock, punk and folk, like a possessed, whirling dervish spinning wildly across a genre map. The crowd looked like they didn’t know what hit them, but they went along for the ride, happily growing more and more ape-shit with every song. And the wilder it all got, the more Hearst and Trent seemed in complete control: two devil-may-care misfits from South Carolina, standing confidently in the eye of the storm and whipping a small Texas bar into a frenzied state of joyous raucousness.

That was two-and-a-half years ago, and I can still remember that show like it was yesterday. Not necessarily all the songs they played (apart from gems like “Gasoline” and “Boxcar” from their 2008 debut, Shovels and Rope, and probably a preview song or two from O’ Be Joyful, their July 2012 sophomore album that ended up really kicking their career into high gear); but I for damn sure remember that dizzying feeling of “whew, that was something!”

And as it turns out, Hearst and Trent remember that show, too.

“Oh, yeah, I remember playing in the barrio on the floor,” says Hearst today with a hearty laugh. “I believe the guys in Buxton got us that gig, and we were grateful to be able to play it!” Trent, sitting right next to her, smiles and nods in agreement.

“We’ve always been grateful to play any floor or stage that will have us,” he says. “It’s been a wild ride over the past couple of years, but we know that we could be back playing at the Tradewinds of the world next week possibly. So many bands have only a brief moment of success, but we’re trying to make music as our careers.”

Judging from some of the highlights from that “wild ride,” so far, so good. In the wake of O’ Be Joyful, Hearst and Trent found themselves touring with Jack White (who apparently still has an affinity for a killer co-ed two-piece band) and performing the album’s irresistible single “Birmingham” on the Late Show with David Letterman. In the fall of 2013, they took home two awards at the Americana Music Association Honors and Awards ceremony in Nashville: Song of the Year for “Birmingham” (beating such notable competition as the Lumineers’ smash “Ho Hey” and JD McPherson’s stellar “North Side Gal”) and Emerging Artist of the Year.

As career-making calling cards go, “Birmingham” still holds up a year later. But that “emerging artist” tag didn’t fit Shovels and Rope for long. It’s Sunday, May 31, the last day of the four-day Nelsonville Music Festival in central Ohio, and Hearst and Trent are sitting in a VIP tent, waiting for their time slot. Alt-country stalwarts the Bottle Rockets and Texas songwriting legend Ray Wylie Hubbard have already performed and are ambling around the backstage artists’ village. Next up is Memphis’ soulful roots marvel Valerie June, whose Dan Auerbach-helmed album, Pushin’ Against a Stone, garnered widespread critical acclaim throughout 2013. Not a bad day’s lineup for a festival whose first three nights were already headlined by Jason Isbell, Dinosaur Jr., and the Avett Brothers. And tonight, that honor falls on Shovels and Rope.

Consider them fully “emerged” then — even though they’re not done rising yet by a long shot. By the time you read this, Hearst and Trent will have already logged their second appearance on late-night television (playing Conan on Sept. 3), and their third album, Swimmin’ Time, will be well on its way toward roping even more Americana music fans into their corner. Ditto the full slate of festival, theater, ballroom and other marquee concert dates lined up through the end of 2014. Fortunately, their heads have not grown in tandem with the size of their crowds and buzz.

“We’ve made this happen one Tradewinds at a time,” says Hearst.

“A few years ago, we literally wrote a plan out on a piece of paper,” she continues. “And so many things we wrote down have come to fruition and so many of our wildest dreams have come true …”

She pauses with a grin. “Now, keep in mind, we have very reasonable dreams,” she adds, letting loose a gleeful, contagious laugh. Trent chuckles, too — though it’s pretty clear that they haven’t taken a moment of their ride for granted. You get the feeling these two pinch each other a lot, and not just out of genuine affection.

“We still feel like we’re getting away with something,” says Trent.

Plenty of Shovels and Rope fans would likely beg to differ. So does fellow artist Hayes Carll, who has been an avid champion of Shovels and Rope ever since he struck duet gold in 2011 by cannily casting Hearst as his foil for his tongue-in-cheek opposites-attract anthem, “Another Like You.”

“There are a lot of reasons why Shovels and Rope have taken off,” offers Carll, who won his own Americana Music Song of the Year Award in 2008 for “She Left Me for Jesus.” “They’ve worked their asses off, made the most of every opportunity and been really smart along the way — but really it just comes down to them being incredibly good. They are ridiculously great singers, writers and musicians. They pour their heart into it and there’s no faking it. They can sound as powerful in a living room as they can in Carnegie Hall.

“People want to see something real,” Carll says, “and they are about as real as it gets.”

A Joyful matrimony

Speaking of being as real as it gets, there is at least one thing Hearst and Trent have managed to “get away with” thus far in their Shovels and Rope career: avoiding the tricky tightrope act of pretending to be something in the spotlight together that they’re not in private. Musical chemistry and personal chemistry are by no means always in sync in such relationships; indeed, the opposite is more often than not the norm, as countless artistic partners ranging from Mick and Keith of the Rolling Stones to Joy Williams and John Paul White of the Civil Wars could readily attest to. But Hearst and Trent, married since 2009, are one very happy exception to that rule. As close as they seem and sound together when performing, it becomes clear within moments of meeting them that they’re even closer together offstage.

Whether sitting for an interview in the festival’s artist’s tent or watching another act’s set from the of the stage, they position themselves close to one another at almost all times, with Hearst lovingly putting her arm around Trent or giving him a quick peck on the cheek with a casual regularity that’s somehow more endearing than eye-rollingly sappy. She’s by far the more robustly animated of the two, coloring her conversation with all manner of funny voices, silly phrases and even sound effects to draw anyone near into her world. That makes Trent the de facto quiet one, but his more understated disposition doesn’t come across as awkward shyness or discomfort so much as genuine contentment. He smiles softly and chuckles where his wife beams or roars with laughter, and leaves the lion’s share of playful stage banter in front of crowds to her while he takes the reins in the studio as their producer.

They complement each other so well, in fact, that it’s fitting that their breakthrough song, “Birmingham,” tells their story in a nutshell, chronicling the courtship of the “Cumberland daughter” who “couldn’t fit in” and the “Rockamount cowboy” who “spent five years going from town to town/waiting on that little girl to come around.” After a verse or two of touch-and-go near misses, the stars align in Birmingham and they begin again as one — “making something out of nothing with a scratcher and a hope/with two old guitars like a shovel and a rope.”

It ain’t your typical love song, but it says it all so well, it stands alone as practically the only love song in the Shovels and Rope repertoire — or at least the only one explicitly about them.

“It’s kind of silly for us, five years into this beautiful marriage, to get all lovey-dovey,” explains Hearst. “Maybe if we become estranged, we’ll write more typical love songs. But there’s too many other good stories to tell. And besides, I already wrote all my good love songs when I was pursuing this fella over here!”

She laughs heartily at this, but Trent demurs with a quiet smile. “It was a mutual pursuit,” he clarifies.

Both pursuers were already seasoned performers by the time they first crossed paths, and they continued working on their separate solo careers for a spell even after their first album together, 2008’s Shovels and Rope. Tellingly, that record was actually co-billed as a “Cary Ann Hearst & Michael Trent” project, making O’ Be Joyful their official debut under the Shovels and Rope banner.

Trent is a native Texan, born in Houston, but his family moved to Colorado when he was 2 and he came of age in Denver. He describes both his family and his high school as rather conservative, though neither could curb his adolescent affinity for rap, metal and hard rock. Not that they didn’t give it their best shot, trying to nudge him toward bluegrass or at least contemporary music that skewed a little more wholesome in spirit. “My parents are cool, and they do like different kinds of music, but one time, they went to a Christian bookstore and bought me a cassette from a Christian rap band called Rapture,” he recalls. “So I just put tape over the top of the cassette holes and I recorded Slippery When Wet over it.”

It was in high school that he put together and fronted his first band, an indie-rock outfit called the Films. “We practiced in my friend’s basement in Boulder — his mom was really cool about it, and she would bring us snacks when we practiced,” he says. “We were so young, none of the bars would book us, so we just played a few battle-of-the-bands gigs for a while.”

The Films (who originally called themselves Tinker’s Punishment and relocated to Charleston, S.C. in 2003) ended up having a fairly good run, touring both nationally and in Europe and even landing a major-label record deal. That fell apart as soon as it came together, but the band went on to release two albums, 2006’s Don’t Dance Rattlesnake and 2009’s Scorpio, before ultimately calling it quits. By then, of course, Trent had already met and started collaborating with his future wife.

The oldest of three girls, Hearst was born in Jackson, Miss., but grew up mostly in Nashville, where her mother and musician stepfather (the “Delta Mama” and “Nickajack Man” from the opening line of “Birmingham”) raised her on a varied musical diet of Molly Hatchet, John Prine, John Lee Hooker, Fleetwood Mac, Motown, and ’80s soul and pop. By the time she had her first gig at 14 — at Music City’s now-closed Guido’s Pizzeria — she was already playing in two bands. “I went to a cool High School in Nashville for math and science,” she says. “So being a musician, even in Nashville, kind of set me apart in a good way and everyone there was really supportive. We would play everything from Billy Joel songs to Salt-n-Pepa.”

She moved to Charleston for college and continued playing, finding her own voice as a songwriter on the local scene and eventually picking up enough out-of-town gigs to cross paths with Trent for the first time at a show in Athens. But it wasn’t until Trent’s band landed in her college town that the wheels of fate (and love) really started turning. As Hearst recounted in a blog entry on Shovels and Ropes’ website, she’d “been hanging out singing in bars in Charleston, half drunk most of the time, not really up to much. I felt at times like I was rusting in place, waiting for some great adventure to come along. When the Films moved to Charleston, with their ameri-trash glam rock-a-mount cowboy swagger, I was good as done for.”

It would still be another five years before they got around to making Shovels and Rope, though, by which time both had already released debut solo albums: Hearst’s Dust and Bones in 2006 and Trent’s Michael Trent in 2007. In 2010, a year after marrying and two years after their co-billed duo album, they each issued sophomore solo sets: Trent’s The Winner and Hearst’s Lions and Lambs. Although neither album (nor Shovels and Rope, for that matter) garnered quite the buzz and national attention that 2012’s O’ Be Joyful eventually would, a fittingly spooky cut from Hearst’s record, “Hell’s Bells,” did creep its way onto an episode of HBO’s hit supernatural drama True Blood (and, subsequently, onto the 2011 soundtrack compilation True Blood: Music from the HBO Original Series, Vol. 3, alongside tracks by Nick Cave and Neko Case, Jakob Dylan and Gary Louris, and Nick Lowe).

But it was with Hayes Carll, not Sookie Stackhouse, that Hearst made her most memorable pre-O’ Be Joyful splash on the Americana music scene. Out of all the quality tracks on the Texas songwriter’s acclaimed fourth album, KMAG YOYO (and other American stories), it was the hilariously ribald, politically charged “Another Like You” that immediately stood out most of all — and in large part thanks to Hearst’s sassy rasp singing the lines of a hot-headed but drunkenly horny neo-con. (The video, featuring Carll and Hearst and a cameo by left-wing/right-wing odd couple James Carville and Mary Matalin, was quite a hoot, too.)

Three years and many mornings after later, Carll and Hearst share two appropriately slightly different he said/she said versions of how their one-off musical hook-up came about.

“Hayes got lucky because he couldn’t get any of the other singers he liked!” Hearst offers with a laugh. “So, I was suggested to him by Lost Highway, even though Hayes barely knew me from a hole in the ground. But we went out for a few drinks, had some fun, and I’m so thankful that it worked out the way it did.”

“Cary Ann actually was my first pick for that song,” Carll counters. “I had played with her once in Charleston a few years earlier, and I just remember being blown away by her voice. As we led up to the recording, I was kicking around a lot of well-known names to sing the song with, but none of them felt quite right. I kept thinking about Cary Ann and how much fun it would be to hear her on it. That ended up being one of the better decisions I’ve made because not only did she slay the song, but that led to us doing a lot of touring together and becoming great friends along the way.”

Hearst performed the song with Carll onstage at the Ryman Auditorium at the 2012 Americana Music Honors and Awards. She was back a year later with Trent as Shovels and Rope, stealing the show with “Birmingham” and collecting two of the evening’s biggest awards from “Mr. Americana” himself.

“Cary Ann and Michael have just blown me away from the first time I saw them,” enthuses Jim Lauderdale in his deliberate drawl. “They are so talented, charismatic and deep with their material. They’re what other artists aspire to be like. They complement each other so well, too. Cary Ann has so much of what I like to call vivaciousness, and Michael has so much reserved power in what he does. And the music that comes out of them is nothing short of amazing.”

Swimming against expectations and dancing with the devil

Back in 2010, Jace Freeman of The Moving Picture Boys, a Nashville-based film production company, got a tip from a friend about a talented couple of up-and-coming songwriters from South Carolina worth checking out. After meeting Hearst and Trent and hearing their music himself, he was intrigued enough to want to work with them on a video or two, just to capture some of their chemistry and creative sparks on film. The next thing he knew they were off and running on what would become a feature-length documentary.

Shovels and Rope just have that way about them. Once they grab your attention, there’s no letting go.

“We definitely did not intend to be filming for three years,” admits Freeman. “We started out with a smaller project, just documenting the process of making what would become O’ Be Joyful. But we were attracted to their DIY approach, and after filming for a couple months, we realized that there was a more interesting story developing at that point.”

The beautifully produced film, titled The Ballad of Shovels and Rope, has already screened at a number of festivals, including the Nashville Film Festival where it won the Ground Zero Tennessee Spirit Award for Best Feature. A DVD release is due soon. But the story of Shovels and Rope is still developing, with Swimmin’ Time marking the beginning of a brand new chapter — if not a whole new adventure.

“We definitely feel pressure to follow up on what we’ve done,” Trent says, acknowledging the inevitable weight of heightened expectations that comes with the territory of Joyful-level success. Their goal going into the studio for Swimmin’ Time was to turn that pressure into inspiration.

“It all starts with the songs, which is the kind of pressure we put on ourselves,” Trent continues. “We didn’t try to get away with something we didn’t think was great, and when we did go into our studio, we challenged ourselves to not make something boring or something we’ve already made. At the risk of sounding pretentious, we also want to challenge the people that follow us too. We want to give them something truly new to hear.”

But Hearst is quick to add that, while they certainly didn’t want to make “O’ Be Joyful II,” “it’s not as if we’ve reinvented ourselves.”

“It’s still us,” she insists, “and people are still going to recognize what we’re doing, we think. I love the way this record’s tough moments are our toughest moments ever and the sweet moments are some of our sweetest. Like on ‘Save the World,’ we allowed ourselves to be as tender as we wanted and needed to be.

“We have this spectrum that we feel like our own music floats between,” she continues, holding her hands about two feet apart from one another. “And that spectrum seemed to widen as we made this record. We had more freedom, so we took more risks, but we also had the freedom to still be ourselves.”

On the opposite end of that spectrum from the genteel “Save the World” sits Swimmin’ Time’s foreboding, low-rolling “Evil” and the stomping, sinister “Ohio,” arguably the oddest, funkiest and most intriguing song Shovels and Rope have turned out yet. It’s a sordid tale that exemplifies the impeccable manner in which they defy easy categorization even within the free-range fields of the Americana realm. Trent and Hearst purposely went a little wild on spinning a yarn that would sound as menacing as it read.

“That was a tricky one to begin with because I didn’t know what I wanted to do with it,” Trent admits. “I felt like it was too slow, but I liked the story in the song. Cary was the one that made sure we kept working on it and that’s when we added the horns on it.”

And the horns Trent mentions aren’t your run of the mill brassy blasts.

“It’s a funeral march kind of song,” Hearst says, then punctuates her point by mimicking a deep, horn-like bellow just like the one on the record inspired by the darker sounds of the Crescent City’s musical heritage. “We’re both fans of the music of New Orleans, and I’m a little obsessed with New Orleans, actually. So the song is about a guy who’s down on his luck and doesn’t know why he’s getting his ass handed to him in Ohio. He talks to a friend of his from Dallas when he makes a trip to Louisiana, who tells him that he’s been making a ton of money running scams on people in Ohio, and the guy realizes he’s one of the people his friend has scammed. I thought it would be prefect to set that kind of story to a slow dirge, and I put my foot down about keeping it on this record.”

Fortunately for her, though, Hearst didn’t have to lock horns with an outsider in order to get her creative way. Nor did Shovels and Rope have to watch the studio clock. Swimmin’ Time was recorded in the couple’s house in Charleston, with Trent at the helm for production and engineering — just like he was for their last two records together.

“I pity the poor producer that tries to work with us and our crazy schedule,” Hearst says with a laugh. “That producer would run away with his tail between his legs. What we have is great because Michael is patient and has a laser focus that I benefit from.”

Trent agrees with a nod. “Doing it ourselves is really working for us,” he says. “I’m not saying we’ll never have someone produce us, but we’re not out of ideas, and that’s really exciting.”

To illustrate that point, Hearst enthusiastically recalls an unexpected holiday excursion a few years ago that led the couple to dig deep and find a new way to sing together without relying on sweet harmonies alone.

“Michael and I went to a Poarch Creek Indian pow wow three Christmases ago where my Daddy lives,” she says. “And for me, listening to the communal singing of the Creek Indians and their war singing changed the way I thought about singing forever. Now, when we sing a song that way, I call it our ‘Indian War Call,’ which is what we did for ‘Fish Assassin.’ It’s a pow wow song, and we just lean back with our shoulders straight, mouths wide-open, and locked-in eyes.”

Hearst is practically jumping in her seat as she says this, as if just thinking about belting out that particular tune — or really, any song — with her husband is enough to get her giddy. Trent as usual stays more composed but his shared enthusiasm is belied by a wide grin. “For this record, we did all of our singing with our microphones really close and facing each other,” he says. “So we were literally singing to the other the whole time.”

The resulting kinetic charge of their voices blending and whoopin’ and hollerin’ against and with each other can be heard running through the entire record, which throws off electric sparks every bit as intense as the ones Hearst and Trent effortlessly generate live. It’s a primal, sexy energy that can imbue a pow wow song about fishing with as much passion and feeling as their colorfully woven stories of struggle, desire and wicked fun. That heat you feel coming off Swimmin’ Time’s opening track and lead single, “The Devil Is All Around,” is as much a gleeful summons as it is a scare-the-lights-outta-you warning couched in good-old-fashioned revival preaching. Shovels and Rope may not have a lot of love songs in their arsenal, but they can sing the hell out of a song about sinnin’ and redeemin’.

“We were both raised in the way where going to hell was a regular thing to fear,” Hearst explains. “Michael grew up in a more religious house than I did, but I still came up in a very hellfire-and-brimstone kind of way, and that’s a scary thing for a child! So in some ways that can be good and in some ways it can be bad, but we both speak that language and we understand the overall reasons that people look for spiritual peace, and its always on our minds whether we’re active in a church or not. It’s such a part of our foundations that it just comes out in our writing without us meaning for it to.”

It’s oft been said that the devil gets the best tunes, and with “The Devil Is All Around,” “Evil,” and “Ohio,” Shovels and Rope sound more than happy to oblige. But lest their folks back home or childhood preachers or anyone else get too worried, Hearst and Trent both offer assurances that however far they may roam, they’re still making a joyous ruckus with their hearts in the right place.

“None of us are perfect and we’re a bunch of messes, but we do the best we can,” Hearst insists with disarming sincerity. “I will always choose good over evil every chance I get.”

Rock of ages, cleave for me …

Our conversation winds to a close just as Valerie June’s marvelous set is reaching what sounds like its peak moment of intensity. Shovels and Rope, the main event, are due up next to bring the Nelsonville Music Festival to a rousing close; but rather than stealing away to find a quiet spot to get ready, Hearst and Trent elect to grab a few more beers out of the cooler in the corner of the tent and run over to catch June’s last few songs from the back of the stage. They note that although they’ve already played a number of other festivals with June, they’ve never had much of a chance to see her in action. Watching the Tennessee-born songstress tear up the stage with only her voice and her banjo, it’s easy to grasp why she’s generated so much buzz of her own over the last year — and even easier to imagine any act that has to follow her feeling a little nervous. But Hearst and Trent, standing arm in arm, just smile and drink it all in like happy fans enjoying the best seat in the house.

“All of this feels like a fever dream that didn’t really happen, but I wish it had,” Hearst enthuses — laughing a little at how convoluted her thought sounds out loud. But there’s no doubting how much she absolutely means it.

“This stuff doesn’t get old and every day we wake up now is just good,” she marvels as her husband nods. “Our life is just crazy good.”

Half an hour later, she and Trent have moved from the back of the stage to the front. Their gear arsenal has doubled in size since the first time I saw them — there’s now a snare and a kick-drum, along with a small keyboard and an extra guitar — but it’s still just the two of them, dwarfed by a stage big enough for the Polyphonic Spree. And even though June played a one-woman-show, the two of them somehow seem to take up even less of the stage — perhaps because Hearst, dressed in a cute navy summer dress with bold white polka-dots, and Trent, sporting a brown blazer over a white tank-top, never stray more than a yard apart from one another throughout their entire set.

Being a Sunday, the last day of the festival is wrapping up earlier than the first three, so it’s still broad daylight, allowing them a perfect view of the few thousand music fans in front of them packing the grounds of Hocking College. Hearst beams a big, fun-loving grin out over them, nods at her husband to count off the first song, and just like that, I’m back at Tradewinds in early 2012.

Sure, everything around them is bigger: the stage, the crowd, their name — hell, even their sound, with their gutsy, rootsy acoustic stomp amped loud enough to reach the back of the field and their Indian War Calls filling the stage and open sky like the indomitable flood waters they sing about in Swimmin’ Time’s title track. But at the heart of it all it’s still just a Cumberland Daughter and a Rockamount Cowboy, locked-in on each other and in complete control of the moment but looking for all the world like they’re getting away with having the crazy good time of their lives. And when Hearst belts out the opening line of “Birmingham” — “Delta Mama and a Nickajack Man …” — and is answered by what sounds like the entire crowd joining in with her before the end of the first verse, well … whew, that’s something.

Such a great read. I hope this got to Cary Ann and Michael!