Texas Heavy: The Quaker City Night Hawks, from left, are Patrick Adams, Sam Anderson, Aaron Haynes, and David Matsler (Photo by Karlo X. Ramos)

By Christian Wallace

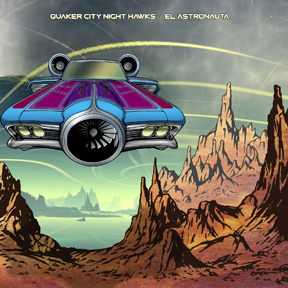

When the brain is asked to communicate “Southern rock” to the mind’s eye, it’s a safe bet that those first neural signals will not be depictions of outer space. A Confederate flag tattooed to the bumper of a souped-up Trans Am, a column of dust trailing skyward while Skynyrd wails in the waning twilight, sure — but trench-coat cowboys piled into an intergalactic hotrod rocketing across a desert planet to rumble with a cyborg buzzard tricked out like some sort of avian Swiss Army knife?

It sure ain’t “Sweet Home Alabama,” but once you’ve seen the Quaker City Night Hawk’s new video for “Mockingbird” and mainlined the Fort Worth band’s latest album, El Astronauta, you may never think of Southern rock — or space, for that matter — the same way again.

On June 23, Rolling Stone debuted the music video on their website, describing it as a “mind-bending” blend of “Heavy Metal sci-fi and Sergio Leone.” The Heavy Metal reference harkens to the 1981 cult film, an animated anthology of trippy sci-fi stories scored to classic (then contemporary) hard rock. It’s a fitting descriptor given the graphic-novel-style animation and rocket-launcher violence deployed in the “Mockingbird” video, which brings El Astronauta’s fantastical cover art to life. “I saw the cover of the record, and the first thing I thought of was Heavy Metal,” enthuses director Charlie Terrell. “I said, ‘That’s the way the video should be.’”

On June 23, Rolling Stone debuted the music video on their website, describing it as a “mind-bending” blend of “Heavy Metal sci-fi and Sergio Leone.” The Heavy Metal reference harkens to the 1981 cult film, an animated anthology of trippy sci-fi stories scored to classic (then contemporary) hard rock. It’s a fitting descriptor given the graphic-novel-style animation and rocket-launcher violence deployed in the “Mockingbird” video, which brings El Astronauta’s fantastical cover art to life. “I saw the cover of the record, and the first thing I thought of was Heavy Metal,” enthuses director Charlie Terrell. “I said, ‘That’s the way the video should be.’”

Although he was an experienced videographer who’d worked with a wide range of artists from Eminem to Mastodon, Terrell admits that he never actually directed an animated video before. Still, he jumped at the chance to helm the project. “I love challenging myself,” he says with a laugh, “and trying new stuff that I don’t know how to do.”

The first thing Terrell had to do was find just the right animator. After a couple of dead ends, he discovered Charlo Nocete, an illustrator based in the Philippines whose style proved a perfect match for his vision. After that, all he had to do was bring the band on board with his concept. Terrell, a nine-year Austinite, showed up unannounced at one of the Night Hawks’ rowdy, late-night gigs during this year’s South by Southwest in March. He bought the boys a round after their show and delivered his pitch from the bed of his rusted-out ’53 Chevy pickup. His idea, in a nutshell, was to cast the Night Hawks — and their “bitchin’ hot rod,” as seen on the album cover — as the saviors of an alien industrial hellhole under siege by the aforementioned villain buzzard and a gang of reptilian henchmen. (Spoiler: After a generous exchange of laser and rocket fire and good-old-fashioned, bare-knuckled pugilist whoop-ass, the good guys win.)

“They loved it,” recalls Terrell, who left the meeting with both Quaker City’s blessing and additional inspiration gleaned from the band’s own ideas about “mixing Western and space.”

Pour a few fat fingers of Texas boogie, Floydian prog, soulful R&B, and yes, classic Southern rock into that cocktail, and you’ve got the basic recipe for one of the most heady records to come out of the Lone Star State (or anywhere else, really) in 2016. The early buzz on El Astronauta was strong going into SXSW, two months before the album’s release in late May, and the Night Hawks only stoked that hype throughout their seventh trip down to the festival. Just hours after their post-gig meeting with Terrell, a mid-afternoon set at Lone Star Music’s day party at Threadgill’s World Headquarters would find the band proving themselves to be every bit as formidable onstage as they are on record — let alone in cartoon-avatar form as scruffy-bearded guardians of the galaxy.

At center stage stood singer Sam Anderson, playing rhythm guitar and bringing much of that soulful inflection to the band’s sound, his delivery smoky but smooth like a slab of warm butter melting over Kobe steak. He’s the shorter of the two lead singers, with long caramel-blond hair falling just above his guitar and a smattering of freckles across his face. Standing in stark contrast to Anderson at stage right was his co-frontman and the band’s lead guitarist, David Matsler. Where Anderson’s jeans flared like bell-bottoms, Matsler’s were ranch-hand straight down to his boots, which were as black as his cowboy hat and close-cropped beard. Like Anderson, Matsler contributes both songs and lead vocals to the group, but it’s his guitar playing, heavily influenced by the blues and folk icons such as Bob Dylan, that’s the marrow of Quaker City’s sound. As a soloist, he doesn’t rely on masturbatory pyrotechnics; his riffs feel methodical and deliberate, with an emphasis on the emotive capacity of a single string bent over a single fret rather than a slurry of machine-gun arpeggios. On the opposite side of the stage was bassist Pat Adams, distinguished not just by his long, cinderblock-thick black beard, trademark trucker hat and Buddy Holly glasses, but by the key role he plays in contributing to the full harmonies that characterize much of the band’s catalog. Rounding out the rhythm section was drummer Aaron Haynes, the newest Night Hawk. A longtime friend who was also a member of Anderson’s first band, Haynes proved the perfect recruit when former drummer Matt Mabe left Quaker City shortly after the new album was completed.

Blazing through a handful of songs from their first two records and two of El Astronauta’s best tracks (Anderson’s simmering “Something to Burn” and Matsler’s rollicking “Duendes”), the Night Hawks had kids of all ages dancing in the aisles and plenty of jaded, sweaty hipsters raising their cans of Lone Star in salute. As best summed up by one duly impressed white-haired gentleman sporting a well-loved Kerrville Folk Festival T-shirt, they were “pretty fucking good.”

Not bad for the band’s fifth gig in 48 hours. And though the dark clouds gathering overhead would throw a wet blanket over the downtown Austin party later that night and force the cancellation of their last scheduled performance of the week, the Night Hawks came off that Threadgill’s stage still looking primed and ready to take on any challenges — elemental or extraterrestrial — in their way. It’s that same air of steely confidence that fuels El Astronauta, a record on which they willingly push their own boundaries both aurally and thematically to boldly go where no band of so-called Southern rockers has ever dared go before.

“We knew we were onto something special,” offered Matsler shortly after the Lone Star Music party set, as he and the rest of the Night Hawks found a spot at the back of the venue to decompress and begin the first of several interviews we did together over the next couple of months. By “onto something special,” he was referring specifically to the writing and recording sessions for their new album, but the subject at hand could just as well have been about the rest of the band’s year to come. Same difference. Matsler shrugged, stubbed out his cigarette and grinned. “I guess we’ll see how it goes.”

FORT WORTH BLUES

Of course the Night Hawks didn’t start out zipping between stars. The journey that led to El Astronauta started over 10 years ago, in another alien wasteland of sorts, the Llano Estacado of West Texas.

David Matsler and Sam Anderson first met through Lubbock’s small but storied music scene. Originally from Amarillo, Matsler left home in 2003 to study mandolin at South Plains College in Levelland, “the Juilliard of bluegrass.” Anderson arrived in Lubbock later that year from Fort Worth to attend Texas Tech. Anderson declared as an art major, intending to study printmaking and painting, but he soon found himself spending more time with a guitar than with paintbrushes. It wasn’t long before the two were making the same round of open mics.

“Dave was playing a lot of coffeeshop shows, and I was just then starting to play music and write,” Anderson says of their meeting. “That’s what sparked things off.”

While Anderson was getting his bearings on a fretboard, Matsler already played several instruments — starting with guitar in middle school. Matsler learned how to fingerpick from his mother and by listening to her records, a healthy collection of Paul Simon, Bread, James Taylor and other ’70s folk-oriented singer-songwriters. He had worked up enough proficiency with mandolin to earn a place at South Plains, but soon realized that he’d rather be out performing than trying to attain virtuosic perfection. “You’ve got a good ear,” one of Matsler’s professors told him, “but if this is something you want to do, just go do it.”

Soon after meeting, the two were hitting the local circuit of dives and coffeeshops together; Matsler peddling a repertoire of self-penned folk tunes, and Anderson experimenting with alt-country. Eventually they began widening their circle. “We wound up traveling quite a bit, on and off, together,” Anderson recalls. “Just playing all over Texas, trying not to sleep in our car.”

If those threadbare early “tours” were rough on the budding young songwriters, Anderson doesn’t remember them as such. “People ask how hard it is to sleep in a car, and I say, ‘About as hard as it is to lean your seat back.’”

Halcyon as the bohemian life in Lubbock might have been, Matsler and Anderson left West Texas after a couple of years. Anderson transferred to the University of North Texas. Matsler moved to Austin for a spell. Music remained the focus of both their lives, but the results weren’t necessarily matching the effort they were putting into their careers. The two didn’t keep in close contact while living in separate cities, but Anderson made a trip down to Austin to record a rough demo at Matsler’s apartment. Anderson returned to his hometown with a handful of recordings he hoped would land him gigs, and in 2007, Matsler followed him up I-35 to Fort Worth.

“I ended up having a room open up in the house I was living in,” Anderson says. “Dave came up here and moved into the spare room. That’s where we kind of started the whole operation.”

That might have been the earliest germination of Quaker City Night Hawks, but it would take a couple more years for anything to bloom. At the time, Anderson led a group called the Thrift Store Troubadours, and Matsler played guitar with the Black Bonnets. Spending most of their free time hanging around bars with music, they slowly began to ingrain themselves into the Fort Worth scene. “We were part of a wannabe jam scene,” Matsler says, laughing. “A bunch of dudes trying to be The Band, watching The Last Waltz over and over again.”

Apart from their separate projects, acoustic shows and coffeeshops remained prominent aspects of their gigging calendars, but that era was about to end. “We were tired of people talking over us,” Anderson says. “We wanted a rock ’n’ roll band, so they couldn’t.”

Sometime in 2009, Matsler was browsing an antique store when his phone rang. “I got a phone call from Sam,” Matsler remembers. “He said, ‘I’ve got a name for the band: Quaker City Night Hawks.’ I said, ‘I’m in.’”

Anderson hadn’t pulled the name from thin air; he’d turned to another Southerner for inspiration, Samuel Langhorne Clemens. Specifically, the moniker is an allusion to The Innocents Abroad, Twain’s travel book chronicling his 1867 voyage aboard the USS Quaker City to Europe and the Holy Land. Twain’s fellow passengers were a motley crew divided by their religious and socio-economic backgrounds, but their differences seemed to dissipate in plumes of cigar smoke each night when the travelers came together to carouse and play cards. Twain called this collective the Night Hawks.

“I just love how he could write in different vernaculars,” Anderson says of Twain. “I think he was trying to show the difference in people, not as a dividing factor, but as in, ‘Look how weird we all are. We’re all so fucking weird that we have to get along. Look at all this diversity out here. It exists and it’s good. It’s not a bad thing.’”

Anderson and Matsler needed more Night Hawks if they were going to drown out the crowd of conversationalists. They turned to two friends from their tightknit community of Fort Worth musicians. Pat Adams was playing trumphet with Whiskey Folk Ramblers at the time, but he agreed to set aside his horn for the bass. When Anderson called upon Matt Mabe to beat the skins, he said, “I have this idea for a band: ZZ Top but with John Bonham [of Led Zeppelin] on drums.” With that, Mabe signed up, too.

In October 2009, the Quaker City Night Hawks’ played their first show at the now-defunct Moon Bar. “We rehearsed like three hours before,” Anderson recalls. “That was the first time we’d played the songs all together. Right off the bat, everything clicked really well.” Sensing they were onto something worthwhile, the newly-minted Night Hawks went hunting for any place that would have them, accepting every offer that came their way, ignoring critics who warned they were going to over-saturate. They secured a weekly residency at Spencer’s, another expired Fort Worth venue, that allowed the fledgling outfit to find their sea legs.

Before Quaker City was six months old, they were ready to cut their first record. “We had a buddy that had a little home studio,” says Pat Adams. “He said, ‘I’ll record you guys for 50 bucks a tune.’ And we showed up, and he was expecting maybe two or three songs, but we had 15. He was like, ‘What!?’ He was not prepared.”

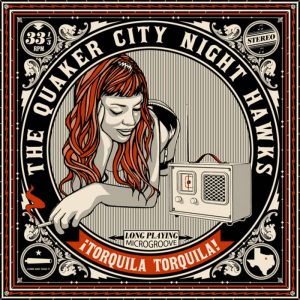

¡Torquila Torquila! was recorded in 12 hours over two days. Although the band was working at a breakneck pace, they were guided by a sure set of hands. Zaq Bell, a veteran sound engineer, produced the Quaker City debut with help from Jordan Richardson (drummer for Ben Harper and the Relentless 7) and Danny Kalb (who’s worked with Rilo Kiley, Taj Mahal, and Wilco). The final result was an album that’s raw and scuzzy, a mashup of menacing blues and ass-shaking boogie.

Highlighting the frenetic energy Quaker City exhibits in their live shows, Torquila holds up as a solid record six years later. Compared to later efforts, the sound is somewhat muffled, especially the drums, giving off a garage-rock edge that makes you feel like you’re in the swampy dive sweltering alongside them. From the first track, Matsler’s guitar work is on prominent display, alternating between funky and ominous. Several songs bear the early hallmarks of that spacey reverb that eventually comes to roost on El Astronauta. Also present on the inaugural record is Quaker City’s accomplished vocal work, Matsler’s rasp against Anderson’s honeyed delivery, with Mabe and Adams filling in the space with high harmonies like a pair of Beach Boys gone rogue or a bluegrass duo that never found Jesus.

Highlighting the frenetic energy Quaker City exhibits in their live shows, Torquila holds up as a solid record six years later. Compared to later efforts, the sound is somewhat muffled, especially the drums, giving off a garage-rock edge that makes you feel like you’re in the swampy dive sweltering alongside them. From the first track, Matsler’s guitar work is on prominent display, alternating between funky and ominous. Several songs bear the early hallmarks of that spacey reverb that eventually comes to roost on El Astronauta. Also present on the inaugural record is Quaker City’s accomplished vocal work, Matsler’s rasp against Anderson’s honeyed delivery, with Mabe and Adams filling in the space with high harmonies like a pair of Beach Boys gone rogue or a bluegrass duo that never found Jesus.

“For us, [Torquila] is a great snapshot,” Matsler says. “That’s exactly how we sounded then — that was the vibe. When we started, it was more of a punk approach to the blues, because we weren’t that good of musicians.”

“That was the first time I’d ever played electric guitar,” Anderson chimes in.

But what the Night Hawks may have lacked in technical virtuosity, they made up in attitude, spontaneity, and earnestness. “As a blues fan,” Matsler continues, “you realize that it’s less about the proficiency and more about the gravitas and creating a vibe onstage, creating an atmosphere.”

On the third track, “Cold Blues,” the self-assured swagger that has become a defining trait of the Night Hawks comes into focus for the first time. Propelled by Matsler’s screaming riffs and an ethereal chorus of “oohs” hovering above the slow-stomp rhythm, it’s a song that evokes both the open road and a rattlesnake bite. A song best heard while astride a custom chopper, the bulge of a Smith & Wesson peeking out between a leather vest and blue jeans, and a cigarette hanging from a snarl. At least that’s the vision one TV exec had when he first heard the song, but that revelation wouldn’t come for another two years.

The Night Hawks didn’t officially release Torquila until February 2012, about a year after they’d wrapped up in the studio. In the meantime, they continued booking every stage in the DFW area. One of their steadiest gigs was the Magnolia Motor Lounge, a mechanic’s garage turned music venue that continues to be a Night Hawks’ favorite watering hole. They were jamming there one night when the sound engineer decided to document the performance for posterity. “We didn’t know at the time that we were being recorded,” Mabe told dfw.com back in 2013. “They didn’t tell us until the morning after. That recording kind of shocked us when we heard the rough mixes, ’cause it was really good.”

Spurred by the regional enthusiasm for Torquila and now with a live EP making the rounds, the Night Hawks were soaring pretty high. And then FX called.

Cowtown Night Hawks: (from left) Sam Anderson, Aaron Haynes, David Matsler and Patrick Adams. (Photo by Karlo X. Ramos)

GET YOUR MOTOR RUNNING, HONCHOS!

Out in sunny Los Angeles, a burned copy of ¡Torquila Torquila! set collecting dust on the desk of Lucas Barton. Danny Kalb, one of the album’s producers who was living in L.A. at the time, had passed the album to Barton, a buddy of his who does music placement for television shows. A year went by. Then one day Barton unearthed the record while going through some old stuff, and put it on. The next morning an email was waiting in Anderson’s inbox.

Barton wanted to use “Cold Blues” for an episode of Sons of Anarchy. The one hitch was FX needed the music immediately. The Night Hawks sent the song over in a mad dash, but before the ink could dry on the paperwork, the studio called for two more tunes.

“We kind of had to rub our eyes a couple times,” Anderson recalls. “It was just kind of bam, bam. That’s pretty typical of the music business. It’s all a hurry-up-and-wait game. There are long stretches of time where you feel like you’re not doing anything. You feel like you’re just treading water. Then all of a sudden it’s escalating so quickly, it’s like getting a drink from a fire hydrant.”

The fifth season of Sons of Anarchy premiered in September 2012. In addition to “Cold Blues,” the show used “Ain’t No Kid” and “Some of Adam’s Blues” in three separate episodes. With their music serving as the soundtrack on one of the most popular cable series in recent memory, the Night Hawks witnessed an uptick in interest. Suddenly, it wasn’t just fellow Funkytowners who were tuning in.

“The cool thing about that show,” Matsler says, “is they have a large audience in Germany, Ukraine, all over the Eastern European block. We didn’t know that until we started getting statistics back from our online tracking. That’s when we realized, ‘Oh shit, this is going all over the place.’”

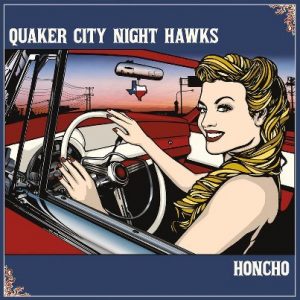

With an ever-widening audience, the Night Hawks went back into the studio. Armed with 18 tracks (later whittled down to 10) and a few months of practice, the band hit the session hard and fast. They didn’t blaze through this recording quite as quickly as the 12-hour sprint through Torquila, but they came damn close.

Honcho was finshed in five days. Matt Smith, the former Dead Horses (Ryan Bingham) drummer who co-produced with Andrew Jackson, said he’d never seen any rhythm section work so quickly. But even if the record was made lightning-fast, the finished product doesn’t sound like a slapdash affair.

The sophomore album shows a maturity and expansion of the band’s technical capabilities. The same blues slathered all over Torquila is there to be sure, but the quartet builds on that sound, at times incorporating folk-pop (“Cast the Line”) and occasionally veering toward indie-rock contemporaries like the Black Keys (“Witch Kitchen”). “Crack the Bottle” and “Fox in the Hen House” are barnburners, while “Lavanderia” is a playful earworm that threatens to burrow deep inside your brain and never leave. Even with these added layers, the homage to ’70s Southern rock remains steadfast in the foreground, especially on “Greasy Night,” which somehow manages to blend Santana with Memphis soul.

The sophomore album shows a maturity and expansion of the band’s technical capabilities. The same blues slathered all over Torquila is there to be sure, but the quartet builds on that sound, at times incorporating folk-pop (“Cast the Line”) and occasionally veering toward indie-rock contemporaries like the Black Keys (“Witch Kitchen”). “Crack the Bottle” and “Fox in the Hen House” are barnburners, while “Lavanderia” is a playful earworm that threatens to burrow deep inside your brain and never leave. Even with these added layers, the homage to ’70s Southern rock remains steadfast in the foreground, especially on “Greasy Night,” which somehow manages to blend Santana with Memphis soul.

Honcho is also the Night Hawks’ most countrified effort, though it’s nowhere near straight hayseed. “Rattlesnake Boogie” sounds like something Ray Wylie Hubbard would tap his boots to, and even James McMurtry might chance a half-smirk, hearing echoes of his own “Choctaw Bingo.” On “Yellow Rose,” a mandolin flutters high and lonesome while both guitars ring out in a tenor reminiscent of Waylon’s Telecaster. It’s also here that the songwriting really starts to sneak up on you. Matsler croons in a gritty drawl: “Now the world shuffles slow through / all the headstones I hid / but there’s a white fire burning as old as the sun / the smoke carries sinners to heaven above.”

Unlike many bands with two songwriters, Matsler and Anderson don’t write together. Instead, the two typically work out their contributions alone, then bring three or four rough demos (typically a phone recording) to the band and see how the tracks might fit together. Like the Drive-By Trucker’s writing duo, Patterson Hood and Mike Cooley, each has his own distinctive approach. The result has been two styles that aren’t so much interchangeable as they are interlocking.

“It’s basically like two guys playing golf together — trading swing for swing,” Anderson offers. “Both have the same goal at the end, but there’s an amount of competitiveness, too. I know I can’t slack off, because Dave’s writing songs at such a high level. I have to make sure that I don’t get lazy.”

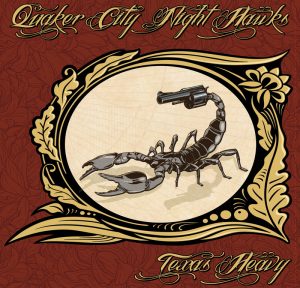

Perhaps more telling of things to come than what the band put on the album is what they left off. Released on the heels of Honcho in March 2013, the Texas Heavy EP was a separate 7-inch single comprised of two songs from the same recording session. More than a couple deep tracks, “Prize to Find” and “Tell It Like It Is” are every bit as realized as the tunes populating Honcho. Why not include them? For one, neither quite fit the flow of the full-length album, which was deliberately structured to mimic their live shows at the time: a steady ascension before a gradual tapering. (That tapering doesn’t include “Sweet Molly,” the final song, a Chuck Berry-ode hopped up on amphetamines that serves as a blistering encore.)

But besides disrupting the carefully plotted cadence, these two Honcho outcasts would have altered the album’s atmosphere. There is a perceptible aural shift on Texas Heavy, grittier and darker, closer akin to the prog-metal of Austin’s The Sword than laconic stoner rock. “Prize to Find” opens with a three-part harmony rising above Anderson’s crushed velvet vocals like sunshine over a river baptism. Just as salvation begins to wash over, Matsler’s guitar plunges into an abyss of distortion. This isn’t redemption: it’s the devil holding your head underwater.

But besides disrupting the carefully plotted cadence, these two Honcho outcasts would have altered the album’s atmosphere. There is a perceptible aural shift on Texas Heavy, grittier and darker, closer akin to the prog-metal of Austin’s The Sword than laconic stoner rock. “Prize to Find” opens with a three-part harmony rising above Anderson’s crushed velvet vocals like sunshine over a river baptism. Just as salvation begins to wash over, Matsler’s guitar plunges into an abyss of distortion. This isn’t redemption: it’s the devil holding your head underwater.

The song earned Matsler “Best Guitar Performance” at Fort Worth Weekly’s 2014 awards. That same year the Quaker City Night Hawks were named “Band of the Year,” beating out newcomer Leon Bridges, who won in the soul category.

At this point, there was no real impetus for the Night Hawks to evolve. Plenty of bands ride the laurels of their early successes, content with rehashing the same sound album after album, stage after stage, night after night. Plenty of fans had taken notice and appreciated what they heard — Honcho was praised across the state — and by now the group was a facet of the Texas honky-tonk and beerhall circuit. They had shared bills with Lucero and J Roddy Walston, toured with Southern sweethearts Whiskey Myers, and opened for Chris Stapleton. But on Texas Heavy, Quaker City began reaching for a new plane, beyond what they had achieved so far. They would set their sights higher for the next album. This time, toward the heavens.

EL ASTRONAUTA & THE NEW SOUTH

“From our side, it’s definitely the most fully-realized record,” Matsler says, exhaling a drag of smoke after the Night Hawks finish their SXSW set at Threadgill’s. “It’s the one that’s the most complete, vision-wise.”

Realizing that vision had taken nearly two years. Quaker City had returned to the studio not long after the completion of Honcho. They hammered out an LP worth of tracks, but when they listened to the rough mixes, something didn’t feel right.

“We’d recorded almost the whole thing,” Adams says, sipping from a beer, “and it was just not jiving.”

“A lot of our songs grow when we play them live,” Anderson elaborates. “They settle a little bit. The more it evolves, the more it sounds like us, the more we put our thumbprint on it. I feel like that’s what’s happened with this batch of songs.”

“We feel like there’s definitely a gestation period with music,” Matsler continues. “If you’re able to let it stew and kind of brew a little bit, you’ll get more out of it.”

“They’re like Pokémon!” Anderson exclaims, as if just struck with the epiphany. “They level up the more you use ’em.” (In Anderson’s defense, this was months before the world was bent over their cellphones throwing poké balls at pixelated Pikachus.)

During that “gestation period,” the Night Hawks had the biggest breakthrough of their career when they signed with Lightning Rod Records. Cliff Wright, a friend and bass player on Leon Bridges’s debut, had passed a copy of the unfinished project to Logan Rogers, another Fort Worth resident and owner of Lightning Rod. Listening to the same rough mixes that Quaker City had decided to shelve, Rogers decided he wanted to release the album on his label, which over the years has boasted a small but stellar stable of artists including Jason Isbell, Amanda Shires, James McMurtry, and Billy Joe Shaver. Besides a brief fling with the Paradigm Talent Agency after the bump from their television exposure, the group had never worked with any type of management. This time their music would have an entire team striving to get the message out, and the timing couldn’t have been better. When the Night Hawks left the studio the second time, they were sure they had just made their best record to date.

El Astronauta was released on May 20. The extra time the band had given the songs to steep on the road paid off. Reviews were overwhelmingly positive. The Dallas Observer put the record in its Top 5 albums of 2016 (so far). Texas Monthly praised the Night Hawks as “Texas’s next great band.” (Full disclosure: my day job is assistant editor at TM.) Garden & Gun proclaimed it a “Must Hear.” Accolades also came in the form of celebrity endorsements; Jimmy Fallon featured the record on his website and Marc Maron tweeted, “Sounds like the rock I grew up with in NM!”

Maron, like so many others, have been quick to note the thread traveling from Quaker City back to classic ’70s rock — Creedence, the Stones, and especially ZZ Top. You’d be hard pressed to find a single article that doesn’t mention the analog between the two Texas boogie-based acts, despite the 50 years that separate their formations. Anderson said himself he wanted the band to echo the hirsute trio from Houston. But on El Astronauta the Night Hawks stake out a new path, distinguishing themselves from the rock legends who shaped their sound, and prove once and for all that this band is not ZZ Top redux. El Astronauta is decidedly not a nostalgia trip; it’s rock ’n’ roll for the future.

“We’re rock ’n’ roll for the New South,” Anderson says. “We’re very much rooted in Southern and classic rock, but with El Astronauta, [Matsler] and I made a very conscious effort to paint a different picture of how people view the South.”

The group approached this concept in a novel way, framing their desire to alter people’s perception of the South against the backdrop of outer space — both sonically and with pointed lyrical content.

“Good evening from Fort Worth, Texas,” Matsler growls on the opener, a foreboding riff simmering beneath him, accompanied by an eerie creak that brings to mind an empty swing-set rocking in the midday heat. The atmosphere grows more portentous as the song continues, and on the last verse you realize that this ain’t no modern-day Cowtown with bustling stockyards and urban cowboys filling Billy Bob’s. This is something else, an alternate universe, perhaps. “You got your sinners and sorrowful saints,” Matsler sings. “But you won’t have a leg to lean on / When they lock your family up in chains / Down here on Main Street.”

And so begins the trip that is El Astronauta, at times dark and sinister, often otherworldly, but always a pleasure for the ears. Quaker City broadens their blues-based sound in part by adding keyboardist Andrew Skates to mix. (Skates is currently traveling the world with Leon Bridges.) “We expanded our musical vocabulary,” Matsler says. “The blues is, in a very positive way, a folk art. It’s a small, community-based kind of music. And now we’re moving it out to a bigger, broader paradigm.”

The embrace of this broader paradigm includes Anderson and Matsler’s lyrical contribution, which, like the “Mockingbird” video, often turns toward science fiction for inspiration. “Liberty 7,” named after a NASA mission, takes a modern issue — “coyotes” trafficking people across the border — and re-imagines the smugglers delivering their human cargo from Mexico to another planet. On “Beat the Machine,” a rider makes his way through a bleak landscape, relaying a grim message: “This war machine and all the death it brings crushing bodies underneath / The wheels of hate unburied soldiers lay under flags out in the street / The final age of the human race, but it’s still up to you and me.” The final line of the song enforces the idea that even in this near-apocalyptic vision of the future, hope glimmers in humanity’s ability to pull itself out of the darkness.

Space Cowboys: “We like to attach that kind of futuristic vision, the spaceship-kind-of-thing, because that means we’ll have made it through this time,” says David Matsler of “El Astronauta.” (From left) Patrick Adams, Sam Anderson, Aaron Haynes, and David Matsler (Photo by Karlo X. Ramos)

Anderson, the only songwriter I’ve ever heard cite a statesman — John F. Kennedy — as an influence on his songwriting, grew up less than 60 miles from the stretch of asphalt where the 35th president was assassinated. The recent slaying of five police officers, also in Dallas, reminds us that five decades later Texas, a large and diverse state, remains susceptible to horrific brutality provoked by dissenting cultural and political ideologies. Anderson addresses this capacity for violence, both historical and current, in “The Last Great Audit,” singing: “We’ll never walk through the gates of His Promised Land / Till we shake off our bloody ancestors’ blues.”

“There are some deep-seated ideas of what goes on down here,” Anderson says, “especially from people who have never been. They’ve got their classic ideas of Texas, some of it’s good and some of it’s not so great. That goes for the whole of the South.”

Matsler agrees, but is skeptical about the “Southern rock” label that so many have used to describe their music. “The only reason we’re Southern rock, is because we’re rock and we’re from the South,” Matsler says. “It’s like, what’s the surprise, man? It’s kind of a strange thing that people think is somehow viable.”

Even if the label is a misnomer, there remains an unmistakable connection between the Quaker City sound and this state. Maybe it’s their allusions to oilfields or odes to Mexican food (an inside tip: pause the “Mockingbird” video at 1:39 and text the number on the billboard to unlock “Queso Blanco,” a secret track). The Night Hawks’ willingness to address social issues, even in a manner more nebulous than direct, is a welcome evolution, and a reprieve from Southern musicians who choose to use their platforms to exclusively wax poetic about redneck pursuits.

Matsler, for one, views the current state of affairs in historical context, likening some recent events to those that transpired four decades before. “Times were bad,” Matsler says of the ’60s. “But when you think of Bob Dylan standards and all of those guys, that’s exactly the society that causes music and lyrics to rise up that wouldn’t otherwise. I think that’s why you’re seeing a resurgence of great musical and lyrical content that’s trying to educate everybody about what’s going on around them.”

Despite the recent violence that devastated the Metroplex and the divisive campaign rhetoric currently marring the entire country, Anderson remains positive. “There’s been a lot of bad blood for decades,” he says, “but I feel like we’re crawling out of that right now. We want to accurately depict that. That’s why I say ‘the New South.’ I want to shed that old mindset. I want to move forward.”

That strain of optimism that runs through the band’s worldview is what lifts El Astronauta from the ashes of a dystopian inevitability to a silver lining of possibility. “Sons and Daughters,” the final song, is a sort of modern, agnostic gospel. The entire band sings the final refrain, “If you can hear me, sons and daughters / Sing out heal me, heal me.”

The decision to take this album to space was more than just the fantasy of “a gang of sci-fi-obsessed ZZ Top superfans” (as Kim Kelly of Vice’s Noisey enthused in one of the album’s first and most widely-blurbed reviews) — it’s the vision of a world that outlives us all. One that moves past our historical shortcomings, and validates the notion that Texans, in one form or another, will carry on.

“We like to attach that kind of futuristic vision, the spaceship-kind-of-thing, because that means we’ll have made it through this time,” Matsler says. “No matter what, we hope that there’s still some cowboys flying around up there in space — if we do this right.”

No Comment