By Richard Skanse

Jimmie Dale Gilmore recalls the night — or at least that particular moment — from more than half a century ago like it was yesterday.

“It was ’65 … or ’66, somewhere in there,” he offers with a chuckle, ballparking the actual year (most likely 1964) when he first ventured beyond the Lubbuck horizon and made it all the way out to California — or really anywhere, for that matter. “This was before I even moved to Austin for the first time,” he explains. “I was just 19, but I was already married with a baby.”

That marriage, to fellow West Texas free spirit and future songwriter Jo Carol Pierce, ran its course before 1967’s Summer of Love, and Gilmore would spend the rest of the decade chasing the wind and his beatnik whim, living on the road and crashing with friends from Berkley to Phoenix to Austin before finally drifing back to Lubbock in the early ’70s. By happy accident, his return to the Hub City coincided with the homecoming of fellow prodigal Panhandle ramblers Joe Ely and Butch Hancock, and of course any fan of Gilmore or Texas music knows what came out of that. But as pivotal as both the Flatlanders and Lubbock are to Gilmore’s origin story, seeing Texas bluesman Lightnin’ Hopkins for the first time in Los Angeles is actually right up there, too.

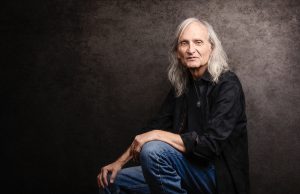

Lubbock wanderer Jimmie Dale Gilmore (Photo by Valerie Fremin Photography)

“I never saw him in Texas, but I did get to see him and meet him at the Ash Grove,” he says, recallng one night in particular at the legendary L.A. folk and roots music den that left a particularly strong impression on him. “This booming voice comes over the p.a., and it’s Ed Pearl, the owner, saying, ‘And now, the man whom even the Beatles have called the most soulful cat alive: Lightning Hopkins!’ Which always struck me, because first of all, he said Lightning, not Lighnin’ — that was just weird. And because there was an old black guy sitting directly behind me, and he said, ‘Yeah, well, what’s Lightnin’ say about the Beatles?’

“That had a really strange effect on me,” Gilmore continues. “I mean, it blew my mind. Because that guy saying that caused me to realize I had gotten it backwards — I had the Beatles elevated above Lightnin’ before that. At the same time, just knowing that the Beatles felt that way about him only made me love the Beatles more! But it really was the most profound question to me. Because Lightnin’ was so much the epitome of the fact that music is mysterious. It’s still unexplainable to me: Listening to his music, how can he be all out of tune, off time, but it’s just so great?”

Dave Alvin, sitting next to Gilmore on the back patio of an East Austin dive bar on a rainy afternoon in late March, nods in agreement. “A lot of it had to do with the fact that Lightnin’ always played in the moment,” he says. “That’s why he’d play a 13-bar blues, just because he didn’t feel like changing at that particular moment. And when someone is that in the present, of the moment — and then when you give yourself over to that, too … I think that was a lot of his power. Because there’s a million better guitar players, but I’d rather hear Lightnin’. That’s the magic.”

Downey Blaster Dave Alvin (Photo by Todd Wolfson)

As a hungry young blueshound growing up in the southeastern Los Angeles suburb of Downey, California, just 20 miles or so from the city, Alvin witnessed that Lightnin’ magic firsthand at the Ash Grove a handful of times, too — albeit probably not at any of the same shows as his Texan friend. “I would have only come up to his knee or mid-thigh at the time,” muses Alvin, who was all of 9 years old when Gilmore first hit L.A.; Alvin and his slightly older brother (and future co-founder of the seminal rock ’n’ roots band the Blasters) Phil didn’t start going to the Ash Grove until around 1969, when Dave was a hardened 13. “So I think Jimmie and I might have only missed each other by moments.”

“Moments,” perhaps … but it would take them a good while longer before they’d eventually catch up with each other for the first time. After the Flatlanders’ shoulda-been-a-contender 1972 debut, All American Music, flatlined on arrival, Gilmore spent the rest of the decade pursuing spirtual enlightenment at a commune in Colorado before returning to Texas in the early ’80s to slowly resume his music career as a solo artist. By then Alvin and the Blasters were already at their hottest, having achieved cult and critical acclaim right from launch with 1980’s American Music. The similar titles of both artists’ first records was of course sheer coincidence — though hindsight hints that fate was already in play.

“I kept hearing Jimmie’s name referenced in reverence in the ’80s,” recalls Alvin. “When we were in the Blasters, we would do these tours through [Texas], and we would do these battle of the bands with the Joe Ely Band, and you’d overhear people talking about Jimmie Dale Gilmore: Like, ‘Jimmie’s in town!’ And I’d wonder, ‘Who is this man?'”

Gilmore’s smile is equal parts humble and apologetic. “I didn’t become aware of the Blasters until after I … well, I had heard of them, but …”

Alvin interjects with a laugh: “Like most people — ‘I’ve heard of them, but never heard them!'”

“Yeah,” his friend admits. “I mean, during that period, I was just … I was keeping up with what Joe was doing from a distance, but I wasn’t there for it; I didn’t see any of the shows. But my daughter Elise was a diehard fan of the Blasters.”

“I think I met your daughter before I met you,” says Alvin, who left the Blasters in ’86 to embark on his own solo career. A couple of albums into it, he signed to California’s Hightone Records, once again just missing Gilmore — who’d been on the label for his first two solo releases — by moments. But they at long last finally connected in the early ’90s, when fellow troubadour Tom Russell recruited both as part of the rotating roster for a songwriter package tour Gilmore describes as “the original ‘Monsters of Folk.'” By then the Ash Grove was long gone, having burned down in 1973, but their respective memories of catching Lightnin’ and other mutual heroes there during the club’s heyday helped seed what was destined to become a longstanding friendship. They got to know each other even better later that decade, when Alvin had occasion to interview Gilmore on assignment for a magazine. Although neither of them can remember the name of the publication (“some ‘men’s magazine,’ but not a skin mag — more like an arty, swanky-ass version of Esquire,” offers Alvin), they both remember the rendezvous fondly. At Alvin’s suggestion, they spent that afternoon hiking a wooded trail “in the middle of nowhere,” just a couple of journeyman Americana legends-in-their-own-time talking songwriting, swapping road stories, and marvelling about all the friends, influences, and philosophies they had in common.

In other words, pretty much just like they’re doing again on this particular afternoon in Austin, 20-odd years later. The unassuming Hard Luck Lounge may not be quite as scenic a setting as a California canyon, but the main topic at hand this time around is special enough on its own: Alvin and Gilmore’s very first collaboration together on record.

Jimmie Dale Gilmore and Dave Alvin on the cover of “Downey to Lubbock,” painted by fellow Americana mainstay Jon Langford

Given the decades of experience, prestige, and genuine friendship between them, it’s no surprise that Downey to Lubbock (which came out in June) is a damn good album: easily one of the best Americana albums of the year, and arguably one of the best that either veteran artist has ever made. Oddly enough though for a pairing so successful and seemingly meant to be, the oft-overused tag “long awaited” doesn’t really apply. That’s because as far as “what took them so long?” projects go, Downey to Lubbock isn’t quite on the same level as Gilmore’s reteaming with Joe Ely and Butch Hancock for the much ballyhooed, official revival of the Flatlanders back at the turn of this century — let alone even Alvin’s reunion, 28 years after leaving the Blasters, with his brother Phil for a pair of warmly received duo albums, 2014’s Common Ground, a tribute to Big Bill Broonzy, and 2015’s aptly titled Lost Time. After all, Flatlanders and Blasters fans waited or at the very least hoped for those better-late-than-never events for decades. But a joint Dave Alvin and Jimmie Dale Gilmore record? Nobody ever even saw it coming — least of all neither of the two songwriters themselves. The whole idea just sorta hit them clear out of the blue. And then, for no other reason than it just felt good — just like Lightnin’, always playing “in the present” — they seized that moment and ran with it.

Up until a little over a year ago, both of them were happily doing their own thing. After three years of recording and touring again with brother, Alvin went right back to working with his band, the Guilty Men, his thoughts likely focused on his next solo project. Gilmore, meanwhile, was by his own account slowing down; although he was still gigging fairly regularly as the mood moved him, he didn’t seem to be in any particular hurry to make another record — even for a guy who waited until his early 40s to launch his solo recording career. His last album, Heirloom Music (a collaboration with the late Warren Hellman, founder of San Francisco’s Hardly Strictly Bluegrass Festival, and Hellman’s band, the Wronglers) came out seven years ago, while the last (new) Flatlanders album, Hills and Valleys, was released way back in 2009.

“I had somewhat jokingly said that I was retired,” explains Gilmore, 73, with a chuckle. “I didn’t have a manager, I didn’t have a record deal, and not really any kind of ambition. But at the same time, I was still playing quite a bit, with the Flatlanders and other people, like Bill Kirchen and Ruthie Foster and Carrie Rodriguez. Basically I had an arrangement with my agent, Mike Leahy, where he said he would keep on booking me but not expect me to work all the time — to only book gigs that I want to do. And that’s really what led into this. I’m still not sure if he’s the one that thought of it, but he was the one that brought the idea to me: ‘You want to try doing some shows with Dave Alvin?’ We were already friends, for a long, long time, and had even been on some shows together, but we had never really actually played together. So I said, ‘Well, sure that sounds … that’s definitly worth trying.'”

Alvin agreed. “I had gone out for about six months with just me and my band, and then this came along and I was like, ‘Yeah, that sounds like fun.’ That was it, for me.”

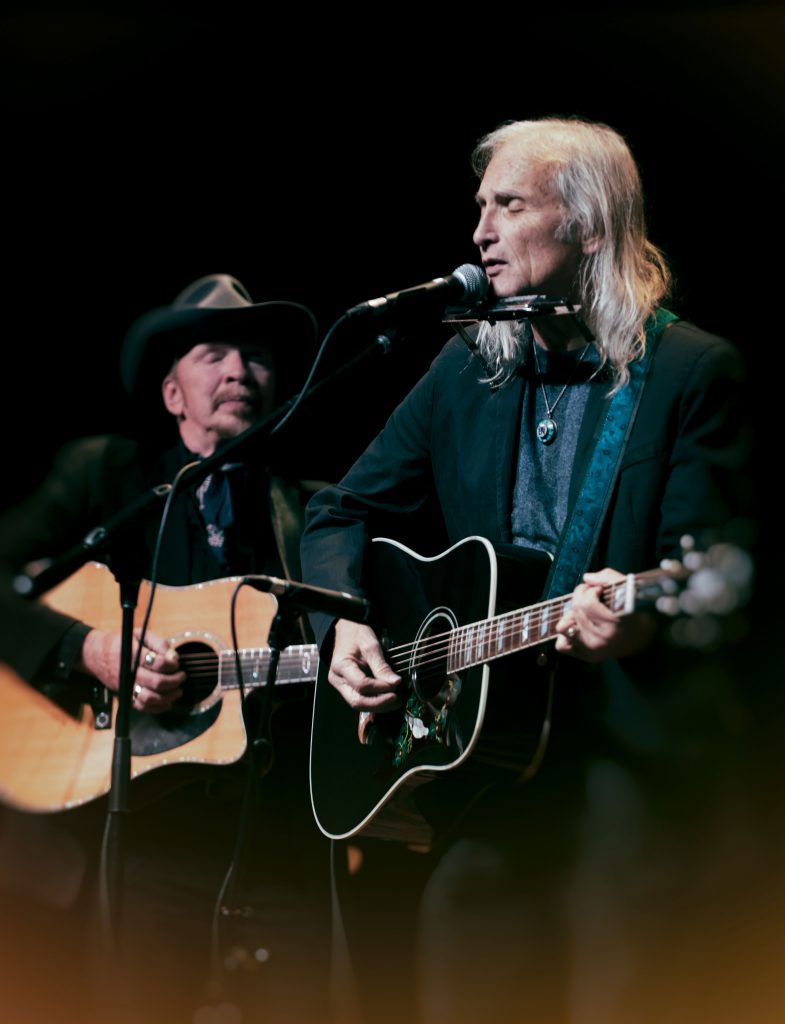

Alvin and Gilmore, aka “Billy the Kid and Geronimo” (Photo by Jeff Fasano)

The duo hit a dozen cities on their first run last year, and from the get-go they realized the potential for it to be more than just a rote excercise in “I’ll play ‘Dallas,’ then you play ‘Fourth of July’ and we’ll go back and forth like that all night.” During soundchecks, or sometimes even in the middle of a show, one of them would bust out an old personal favorite from the memory bank — some reaching all the way back to their formative years grooving to border radio, others of more recent vintage. And often as not, they’d discover to their surprise and delight that the other knew and loved the same songs, too. In the case of Steve Young’s “Silverlake,” there was even a comic awkward moment of debate over who their late mutual friend actually wrote the song for, Gilmore or Alvin.

“Steve was living here in Austin off and on for quite a while, and one night he told me, ‘Jimmie, I’ve got this song I want you to record,'” says Gilmore. “I was honored but procrastinaed and never did get around to recording it, but I brought it up one night during one of our shows. And I don’t think I really noticed it in the moment, but Dave was looking at me kind of funny while I was telling that story about Steve wanting me to record this song he wrote, and Dave goes, ‘Wait a minute …'”

“‘That’s not your song, that’s my song!'” Alvin finishes with a laugh. It turns out Young (who died last March) had once played the song for Alvin, too — at Alvin’s Los Angeles house in Silver Lake — and told the former Blaster he’d written the song for him. “But as soon as I heard Jimmie sing it that night, I was like, ‘Ok, Steve may have written that song for me, but he definitely wrote it for Jimmie to sing.‘”

Either way, it was kismet.

“We found out that there was this whole well of stuff that we already knew together or were able to learn together easy,” says Gilmore. “So I think just about immediately, maybe from the first night in Denton, it was like, ‘Whoah … this is fun!'”

From there, the notion to capture some of that lighting — or in the case their electrifying take on “Buddy Brown’s Blues,” literal Lightnin’ — on record was a no-brainer. Gilmore didn’t have a label home at the time, but Alvin did, and it was none other than Yep Roc Records president Glenn Dicker who urged them along. Downey to Lubbock was recorded quickly over three sets of sessions at Winslow Court Studio in L.A., with Alivin and Gilmore co-producing.

“My original plan was to have us do it half in Texas, half in L.A.,” says Alvin, “but everything went so smoothly during the first batch of sessions that we decided to just do it all out there.” He adds with a laugh that he also “didn’t want to have to drive my whole collecion of guitars and amps to Austin,” but Gilmore — who lives in Ausin — had no complaints with the arrangment. He recalls phoning his wife Janet back home to gush about the sessions, likening the whole experience of recording with Alvin and engineer Craig Parker Adams to being part of a “tight, well-oiled machine.”

“Craig is a brilliant engineer,” agrees Alvin, “and he’s got this room that’s an old foley studio from the 1930s, where they made sound effects for movies; it’s about the size of Sun Studios in Memphis, and it’s just got a really great sound and whole vibe about it. We recorded just about everything live in the same room. We did the first batch of sessions with Van Dyke Parks; I just called him up and said, ‘Do you want to play accordion on this?’ And he was there in like 10 minutes. The next batch of sessisons, like a month and a half later, the special guest was Nick Forster (guitar, lap steel, mandolin) from Hot Rize and eTown; Jimmie had been in a band with him once in Colorado, but they had never recorded anything. And then for the last batch I flew (drummer) Lisa Pankratz and (bassist) Brad Fordham in from Austin, and I added this guy Skip Edwards, a keyboard player who was with Dwight Yoakam for a long time. So, each little section had its magic.”

Other contributors included bassist David J. Carpener, drummer Don Heffington, saxophonist Jeff Turmes, and harmony singers Cindy Wasserman and Gilmore’s son, Colin. “I was worried at first because I was throwing a lot of new musicians at Jimmie,” Alvin continues, “but it turned out a lot of them had actually played with him before, like Don. And, everybody was in awe of playing with Jimmie, so nobody was showboating or being an asshole!”

Showboating for ego’s sake may have been kept in check, but the performances across Downey to Lubbock — especially those by the two men painted on the frame-worthy cover by fellow Americana rocker Jon Langford — are by no means reserved. Alvin’s own monster guitar leads more than live up to his ain’t-boasting-if-it’s-true sobriquet (from the rousing opening title track) as a “wild blues Blaster,” while Gilmore’s equally wild vocal turns prove that there’s a lot more to the “old Flatlander” than just the cosmic folkie with a patented, one-of-a-kind gorgeous ghostly warble. Give the guy room and occasion to open up, and he can flat-out roar.

“People have asked me, ‘what’s the record like?,’ and I say, ‘Well, it’s kind of like some of mine, but it’s not like many of Jimmie’s!'” Alvin says. “Because it’s a side of him that I don’t think has ever really been tapped before. I mean, there’s always been a blues song or two on his records, but not quite like this. Especially nothing like ‘Buddy Brown’s Blues,’ which is just a full-on, you know, rocker. It’s a screamer.”

Gilmore wasn’t just rising to the challenge of matching his partner’s six-string ferocity, either; often as not, he also played the instigator. “He gave me one of the greatest lines I’ve ever heard in a recording session,” says Alvin. “We were doing that song ‘K.C. Moan,’ and I was playing it with a Gibson SG, with this big, gnarly tone. I was like, ‘Well, maybe this is a little bit too over the top.’ And Jimmie goes, ‘You know, Dave, sometimes too much Blue Cheer is better than not enough Blue Cheer.’ [Laughs] So I was like, ‘Thank you! I’ll turn up even more!'”

“It’s just so great when he does,” Gilmore enthuses, “because I’ve always had a love for that really tearing-into-it kind of music. But I guess more or less because of circumstances, or because I had so much other stuff I liked to do, too, I ended up getting kind of … not exactly ‘stereotyped,’ but a little bit, you know? At least on records. So having the chance to really indulge this other side of music that I really love with Dave, that’s a big part of the fun of this for me. But this is the thing, though: He can do that gritty, gnarly thing with taste, so it’s like both facets are there. It’s purely musical, but it’s also just …”

“It’s all the same notes,” Alvin demures, then smiles. “But sometimes you just play them louder.”

Mind, there’s a lot more to Downey to Lubbock than just amped-up blues. At the heart of the album, both literally and figuratively, is an almost surrealistic, sideways psych-folk spin on Chester Powers’ oft-covered (most notably by the Youngbloods) flower power anthem “Get Together” that manages to sound both familiar and otherwordly at the same time, like an oldies station beamed from another dimension. “That’s all based on Jimmie’s voice,” insists Alvin. “When he pulled that one out for the first time, which was pretty early on in our touring together, he didn’t tell me what song he was going to play — he just sang that first line, and I was like, wow. It was a brand new song. I don’t even know if we’re playing it ‘right,’ because I intentionally didn’t listen to the Youngbloods’ version until after we had cut the track.”

Equally stunning are a handful of covers in the more conventional singer-songwriter/folk vein, ranging from Woody Guthrie’s sadly timeless-as-ever “Deportee (Plane Wreck at Los Gatos)” to more contemporary picks like the aforementioned, Gilmore-sung “Silverlake” and deeply felt readings of John Stewart’s “July, You’re a Woman” and Chris Gaffney’s “The Gardens,” both sung by Alvin. Best of all is their duet on the new Alvin original, “Billy the Kid and Geronimo,” an introspective, what-if dialog between two iconic American “outlaws” (with Alvin playing the Kid to Gilmore’s Geronimo, naturally), examining what Alvin calls “that place where myth and redemption meet, or don’t meet.”

Based on the strength of those songs alone, Alvin and Gilmore could have easily pulled off an entire album together of ballads and poignant listening-room fare. Still, it’s the generous helping of those aforementioned “louder” notes that gives Downey to Lubbock such a wholly satisfying, crank-it-up rumble and a disarmingly light-hearted touch. The title track tumbles out of the gate like a feel-good buddy road movie scored to a rolling boil of Howlin’ Wolf boogie, with the two friends swapping humblebrags alternately wryly irreverent and cornball earnest over a house-rattling groove cut by Alvin’s ax licks and Gilmore’s wailing blues harp. Alvin boasts with a proud grin that it took a little bit of “twisting Jimmie’s arm to make him a harmonica player again, after decades.”

“I was like, ‘You’re doing this!’ And he’d say, ‘But I don’t play harmonica!'”

“I love it, though,” insists Gilmore, noting that, “back before Butch and Joe and I started playing together all the time time,” he actually used to play harmonica quite a lot as a solo performer. “I think I was always trying to immitate Sonny Terry’s playing,” he continues.

Gilmore got to see that legend a few times during his salad days of California dreaming, too. After his short spell in L.A., hanging out at the Ash Grove, he migrated up to the Bay Area and found an equally happening blues and roots scene at Mandrake’s in Berkley. Lightnin’ was a regular performer there, too, along with Sonny and his guitar-playing, songwriting partner, Brownie McGhee.

“One of the fun things about making his record,” says Alvin, “was twisting Jimmie’s arm to make him a harmonica player again.” (Photo by Tim Reese Photography)

“I actually got to be friends with all those guys when I was staying in Berkley,” he says, still marvelling at the notion 50 years down the line. As a fan, he idolized them, and he knew they could tell — but McGhee in particular had a way of making him feel at home, almost like an equal. “We would hang out together after the show, sit and talk and things, and several times he even invited me over to his house, but I never did do it — which I’m really regretful of now. But he was such a sweet, big-hearted person that, to me, there was kind of an aura around him of just goodness — like Stubbs! And I feel that in his music, too — in his singing and his songwriting.”

“He was a real underrated guitar player, too,” adds Alvin, then grins. “My brother has a great Brownie story. When my brother was 13, 14 years old, my mom would drive him up to Hollywood, where he got harmonica lessons from Sonny Terry … yeah, I know. [Laughs] Anyway, Sonny and Brownie had adjoining rooms with a door in between, and when my brother finished this lesson with Sonny Terry, Brownie McGhee walks in and looks at my brother and says, ‘What, you don’t want guitar lessons?'”

If only the the other lil’ Blaster had been there, doubtless McGhee would have had better luck in poaching a student that day — even if it meant leaving poor Mrs. Alvin, a former 1930s Vaudeville dancer/contortionist with a sympathetic soft spot for her boys’ musical proclivities, a little lighter in the wallet. Regardless, Brownie’s spirit and influence clearly loomed large throughout the Downey to Lubbock sessions — so much so that Alvin and Gilmore ended up recording not one but two of the Knoxville, Tennessee-born bluesman’s songs. In the end, only one made the record, with the ebullient “Walk On” (co-written with Ruth McGhee and updated with new verses by Gilmore and Alvin) winning closing honors as the perfect matching bookend to the title track. But Alvin assures that their rockabilly blues take on Brownie’s “Ride, Ride, Ride” will eventually be heard, too — along with at least one other noteworthy left-over.

“There’s an Elmore James song called ‘Goodbye Baby’ that Jimmie sings the hell out of,” he raves. “We were like, ‘it’s that one, or ‘Lawdy Miss Claudy,’ and I just went with ‘Lawdy Miss Claudy’ because it was really rocking. But they were all kind of, you know, flip a coin on that one, flip a coin for this one. But I think both of those songs will come out at some point, somehow. They’re too good not to!”

And after that? Asked whether they’re game to keep on walking down this particular road together beyond their 2018 tour dates supporting Downey to Lubbock, neither Gilmore nor Alvin offers a definitive yes. But it’s telling, or at very least encouraging, that neither of them says no, either.

“We could do a whole other album pretty easily,” says Alvin, as Gilmore quickly nods in agreement. Alvin grins. “I never say never to anything, you know.”

This much is certain: If there is a next time around for these two, no matter how long it takes, their fans are going to be waiting for it.

[…] found a way, after years of friendship, to finally “Get Together” on record. (From LoneStarMusicMagazine.com, Aug. 20, […]