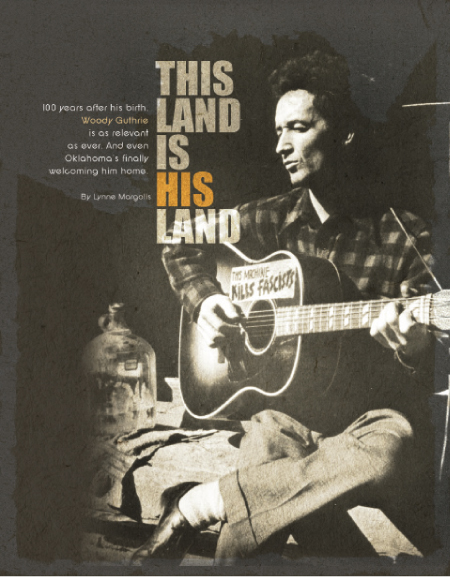

100 years after his birth, Woody Guthrie is as relevant as ever. And even Oklahoma’s finally welcoming him home.

By Lynne Margolis

(May/June 2012/vol. 5 – Issue 3)

“All you can write is what you see.”

That simple sentence, penned by Woody Guthrie, appears at the bottom of the page on which he wrote the lyrics to “God Blessed America,” a song he composed on Feb. 23, 1940, as an annoyed response to Irving Berlin’s chest-thumping cheer, “God Bless America.”

Whether he meant that writing advice as a note to himself — a reminder to stick to his guns — or as words of wisdom for future collaborators (notes he left elsewhere indicate he expected others to share his work, in time-honored folk tradition) will likely never be known. It’s just an asterisked comment on a page of three-ring notebook paper, one of many he filled during his life.

Nor will we ever know for certain why he dropped the verses that conveyed his originally intended message — a rebuke of those willing to allow the excesses of wealth and despair of poverty to co-exist — when he finally began performing the song several years after he wrote it. By then, as Guthrie expert Robert Santelli notes in his new book, This Land Is Your Land: Woody Guthrie and the Journey of An American Folk Song, it had morphed into “This Land is My Land,” “This Land was Made for You & Me,” and finally, “This Land is Your Land.”

What we do know, 100 years after Woodrow Wilson Guthrie was born in Okemah, Okla., and nearly 45 after he died in a New York hospital, is that he was uncommonly brilliant at writing what he saw, and amazingly prolific, too. Though he recorded maybe a few hundred songs, he left behind a few thousand poems and lyrics (unfortunately, without music, which he couldn’t notate). He also left manuscripts, journals, drawings, paintings and other documents — most created in little more than a decade before Huntington’s disease stole his ability to write, speak and eventually, even move or think, before stealing his life at 55. That his most famous song would go on to far eclipse “God Bless America” in popularity is just one of the ironies surrounding it — and the complicated life of the restless troubadour we’ve come to revere as the father of the protest song and pioneer of modern folk music.

Today, Guthrie’s words resonate with as much immediacy as they did when he wrote them — perhaps even more because we know how long some of the issues he addressed, from poorly treated laborers and unsafe working conditions to greedy, unscrupulous bankers and bosses, have troubled our nation. Yet the reason they still matter — the reason this centennial year of Guthrie’s birth is being celebrated with events around the country and internationally — is not because he gave us hits we could dance or fall in love to (most of his songs didn’t even get regular radio airplay) but because he gave us songs that helped us see. And inspired countless others to do the same.

It’s safe to say even those of us who grew up singing “This Land” and other Guthrie classics (that is, most of us) backed into discovering Guthrie via Bob Dylan, Bruce Springsteen, Pete Seeger or others who carry his torch. But however we got to know his work, his status as an American cultural icon has definitely grown as those and other musicians, and his family, have spread awareness of his life and legacy.

“Anybody that says they haven’t been influenced by Woody Guthrie, I would probably differ with ’em,” drawls West Texas singer-songwriter Butch Hancock, a frequent performer at Okemah’s annual Woody Guthrie Folk Festival celebration, aka WoodyFest, held since 1998 around his July 14 birthday.

Hancock and fellow Flatlanders Joe Ely and Jimmie Dale Gilmore grew up in Lubbock, not far from Pampa, where Guthrie lived from 1929-37. Their last album, Hills and Valleys, was directly influenced by Guthrie songs such as “Plane Wreck at Los Gatos (Deportee)” and “Pastures of Plenty”; they also covered his “Sowing on the Mountain.” They’re among many Texas-based artists who pay homage to Woody whenever they can.

Austin-area songwriters Slaid Cleaves, Eliza Gilkyson, Terri Hendrix and Jimmy LaFave, all WoodyFest regulars (where they perform for free), also perform in “Walking Woody’s Road,” the musical and spoken-word survey of Guthrie’s life LaFave created as a revised edition of an earlier production, “Ribbon of Highway, Endless Skyway.”

Another Austinite, multi-instrumentalist Darcie Deaville, is a cast member of the traveling theatrical production, Woody Sez: The Words, Music and Spirit of Woody Guthrie. It grew from a production titled Woody Guthrie’s American Song. The woodyguthrie.org website contains a long list of presentations, exhibits, school programs, films, festivals and musical, theatrical and dance performances dedicated to Guthrie’s life, work and impact — and that’s not counting the centennial-specific events.

“Woody Guthrie at 100” conferences, panels, festival performances and star-laden tribute concerts have been going on since January; they’ll culminate stateside with an Oct. 14 celebration at the Kennedy Center in Washington, D.C. International events continue through early November. Film screenings, panels and performances were held at February’s International Folk Alliance conference in Memphis; in March at Austin’s South By Southwest conference and in Tulsa, where John Mellencamp, Rosanne Cash, Jackson Browne, Hanson and LaFave performed and the Flaming Lips played Guthrie songs on iPads; and in April in Los Angeles, where performers included Jackson Browne, Tom Morello, Kris Kristofferson, Crosby & Nash, Dawes and John Doe.

Unraveling the myth

And yet, despite this exposure, misperceptions continue. America has a way of mythologizing its icons, turning them into one-dimensional representations that may suit our needs, but don’t accurately depict the person.

Guthrie’s image as a hero of the working man and crusader for the downtrodden captures only a sliver of the man, a nomadic balladeer and left-wing union supporter, but also a radio star, newspaper columnist, folklorist, humorist and visual artist. And a passionate lover, wandering husband and absentee father driven by a restless spirit, a childlike playfulness (despite a past haunted by tragedy) and a sense that injustice shouldn’t be tolerated.

In an effort to assess our enduring fascination with this Hemingwayesque troubadour, and why he still looms large on our cultural psyche, Guthrie experts, like-minded performers and two of his three surviving children offered observations and insights during panel discussions at the Folk Alliance Conference and SXSW, and in several individual interviews.

“Guthrie’s been distilled into this colorful, folksy, Johnny Appleseed kind of character,” noted Gilkyson. “He’s a lot rougher around the edges than that. A lot more radical. There are a lot of people who don’t realize whose songs they’re singing. A lot of people on the far right, if they knew more, they’d realize that we’re talking about someone who is accused of being a card-carrying Commie.”

Added Cleaves, “The complexity, the richness of Woody Guthrie is that he was interested in so many different things and wrote about so many subjects. He wasn’t just a union guy; he wasn’t just a lefty; he was an environmentalist and a social progressive, and he worked for equal rights.”

Mentioning the story about how Guthrie, while serving on a Merchant Marine ship during World War II, refused to entertain the sailors unless the ship’s black crew members were allowed to join them, Cleaves said, “He was just a real forward thinker and interested in the forefront of what was goin’ on. He was really into Albert Einstein and modern dance; his wife [second wife Marjorie] was a modern dancer. He was a real Renaissance man.”

At the SXSW panel, Woody’s son Arlo, the famed folk singer, said he believed his father might have possessed a photographic memory. “I met the gal in Pampa who was a librarian when he was a kid,” he related. “She said to me, ‘Arlo, let me tell you something about your father. He was the only man I ever met that came into the library and read every friggin’ book in the library. He didn’t read a subject; he didn’t pick out a shelf. He read every book in the library, about every subject.’” That kind of intellect and memory, Arlo explained, meant he had the ability to relate stories in a special way.

“You’re not singin’ songs in the key of me,” Arlo said. “You’re singin’ songs in the key of everybody.”

But even his championing of the everyman and leftist idealogy aren’t fully understood by those with less than in-depth Guthrie knowledge. While he supported socialist and communist causes, he was never a member of the Communist Party, and wasn’t opposed to making money, either, though he wasn’t keen on getting too comfortable, lest he get soft. He also wasn’t very good at hanging onto his earnings.

His daughter Nora, Arlo’s younger sister and, even in their 60s, his near twin — they share big, unruly manes of curly white-gray hair, as well as world-class comedic sensibilities — has been on an almost two-decade mission to set the record straight regarding her father, whom she knew in life only as a sick man. In 1996, not long after she opened the Woody Guthrie Archives in New York, Santelli, who helped her establish them and was then in charge of educational and public programs at the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame & Museum, created the hall’s first American Music Masters program. He kicked off the series, then a weeklong lineup of seminars and performances to study and honor an early influence on rock ‘n’ roll, with 1988 inductee Woody Guthrie.

As she sat listening to the discourse about her father, Nora recalled, “I realized there were a lot of mistakes in the conversation. Not intentionally, but just because people hadn’t seen what I saw, what I knew to be in existence.”

She remembered hearing Fred Hellerman, one of the original members of the Weavers with Pete Seeger (and producer of Arlo’s Alice’s Restaurant album), say, “Woody didn’t write those moon/croon/June love songs; he was political.”

Meanwhile, Nora had just counted lyrics to more than 60 never-recorded love songs in Woody’s archives.

She had already spoken to Billy Bragg about turning some of her father’s lyrics into songs. The success of the two Mermaid Avenue albums he wound up recording with Wilco inspired a continuing flow of new music made from Woody’s words. They include projects as diverse as the Klezmatics’ album of Hanukkah songs; Jonatha Brooke’s The Works; Note of Hope, the years-in-the-making release helmed by bassist Rob Wasserman, with contributions by Jackson Brown, Tom Morello, Lou Reed, Ani DiFranco and other talents; and New Multitudes, with Jay Farrar, Yim Yames (aka Jim James of My Morning Jacket), Anders Parker and Will Johnson. Mermaid Avenue has just received a deluxe-edition re-release featuring both original albums, plus a third disc of previously unreleased songs and a DVD of Man in the Sand, a documentary about the recording sessions. And Smithsonian Folkways is planning to release a lavish box set titled Woody at 100: the Woody Guthrie Centennial Collection.

In addition to albums, a steady stream of books, including children’s books, have either been published by the archives or received its stamp of approval. Santelli, now executive director of the Grammy Museum in Los Angeles and the force behind the Woody Guthrie centennial celebration, just published This Land Is Your Land: Woody Guthrie and the Journey of An American Folk Song. Austin-based historian Douglas Brinkley, a professor at Rice University in Houston, is publishing Guthrie’s “lost novel,” titled House of Earth. Nora’s walking-tour book, My Name is New York: Ramblin’ Around Woody Guthrie’s Town, comes out in June. She’s also working on a companion audio guide with songs, interviews and spoken-word material.

Preserving Guthrie’s past

When the archives were still located in Manhattan at the office of Guthrie’s former manager, Harold Leventhal, Nora sat one winter day surrounded by notepads, binders and random paper scraps on which her father had hurriedly scribbled thoughts. He was in a constant race to get them down, it seemed, perhaps subconsciously knowing he didn’t have a lot of time before he wouldn’t be able to.

She could never bring herself to wear the white gloves archivists use to protect delicate artifacts from oils, dirt and anything else human hands might leave behind. To her, the coffee-ringed, time-stained volumes of words and images her father managed to hang onto despite his restless, roaming ways are not museum relics. They’re a legacy, yes, but one meant to live and breathe, not lie fallow in sterile metal drawers.

Gently flipping through pages while discussing several projects she had in mind, she said, “The real ideas come from the work itself. It’s like the work just knows what it wants to be.”

Through those archived pages, she’s gotten to know intimately the man she never had a chance to meet in life: the healthy, curious, constantly creating writer and artist.

In April, she explained, “What I’ve been doing for the last 20 years is just trying to get to the next level of knowledge about Woody. So everything I do has that angle to it.

“I never think of my dad in terms of a public figure,” she added. “I create books that I would want to read and records that I would want to listen to. I don’t give two shits if they sell five copies or 500,000 copies. That’s not my job. … My job is to create things that I think would be interesting for other people to know about, learn from, hear.”

Nora, who oversees the archives via the Woody Guthrie Foundation and Woody Guthrie Publications, realized a few years back that she and older brothers Arlo and Joady (named for the character in John Steinbeck’s book, The Grapes of Wrath) needed to secure a permanent home and future for the collection. The family, which takes no corporate or operations grant funding, spends about $100,000 a year to house and maintain the archives, including an archivist’s salary.

“We’ve been happy and willing to keep it going because I feel the least I can do is open up the doors to my father’s ideas to the public,” she said. But the siblings, his only surviving children (all with second wife Marjorie), knew they didn’t want to leave the burden of deciding the archives’ fate to their children, and Nora wasn’t up for trying to create a folk music museum or Woody Guthrie center in New York, despite frequent suggestions from well-meaning friends and fans. “It takes too many fundraisers and cocktail parties and millions of dollars … and I don’t have the wardrobe,” she said with a laugh.

She wasn’t about to turn over the archives to any entity that would curtail access or take only parts of the whole, however. They had to stay intact and accessible, and not be exploited in inappropriate ways.

In a move that may have shocked some Oklahomans, who until recently had barely even acknowledged Guthrie’s Okie connection, the Tulsa-based George Kaiser Family Foundation stepped up to purchase the archives for a reported $3 million. It plans to open the Woody Guthrie Center, including a museum, by the end of 2012, with the archives arriving in 2013.

This is the same state in which, around 2000, a wealthy donor reportedly quashed display of This Land is Your Land: The Life and Legacy of Woody Guthrie, a wonderful Smithsonian Institution traveling exhibit booked for Oklahoma City’s Cowboy Museum. The state had resolutely avoided honoring him for years, though ironically, it had more socialists holding elected government posts while Woody lived there than any other state, as University of Tulsa history professor Brian Hosmer told the New York Times.

At the “Woody at 100” SXSW panel in March, Santelli described the previous week’s big kickoff conference and concert in Tulsa, and noted, “It wasn’t till maybe last week that we felt a warm, kindred spirit with Oklahoma about Woody. He wasn’t treated the same way Jimmie Rodgers or Garth Brooks had been treated.”

Panelist LaFave, who sits on the WoodyFest Advisory Board with Nora and participated in the Tulsa events, responded, “The great joy for me last week was seeing Mary Jo [Guthrie Edgmon, Woody’s sister] live long enough to see the vindication of her brother in that state. His painting is now in the Capitol; ‘Oklahoma Hills’ is the state song. … people that are moving and shaking in Oklahoma are finally coming to terms with it.”

Calling Guthrie “the most famous Oklahoman in the world” and the state’s most historical figure, he noted Guthrie’s sister endured decades of derision by those who labeled her brother an atheist and communist, though she knew how spiritual he was. (Guthrie apparently was a keen student of religion, especially Eastern ones.) Of Oklahoma’s recent Guthrie acceptance, including his 2006 induction into the Oklahoma Hall of Fame, LaFave said, “It was like this scarlet letter was finally taken off.”

Santelli said the Tulsa center will provide extensive research opportunities for scholars, journalists and students “to introduce themselves to Woody Guthrie and vice-versa.”

But he’s even more excited about the education center’s capability to not only tell Guthrie’s story, but put it in cultural and historical context.

“It’s far more encompassing than just a biographical museum,” said Santelli, who served as executive director of Seattle’s Experience Music Project before creating the Grammy Museum. “It takes in everything from the Carter Family and Jimmie Rodgers to Bruce Springsteen. The underlying theme is how music has and continues to act as an agent for social, political and cultural change. And how music can also be the soundtrack or the voice of the disenfranchised in this country.”

Santelli, who lived in Asbury Park, N.J., when Springsteen was finding his musical voice there, noted the Boss alluded in his SXSW keynote speech to the importance of knowing the past “in order to inform the music of the present and inspire the music of tomorrow.”

“I don’t like, necessarily, to dwell on the past even though I’m a historian,” he said in an interview the day after Springsteen’s speech. “There’s gotta be a reason to go deep. You learn from the past. You learn from your mistakes and victories, and use that to inform your lives today.”

That’s Nora’s hope, too. She made several trips to Tulsa to assess whether to send the archives there, and determined, “Not only did they want it, but they were really proud to have it.”

She also confessed, “The mischievous side of me said, ‘Let’s go right in the heart of Oklahoma and let them deal with Woody.’”

The Kaiser foundation’s educational focus was a major factor as well. “Woody is Oklahoma history, it’s American history, it’s World War II history, it’s education,” she said. “An archive is an educational facility where people can come and read Woody Guthrie directly and form their own ideas.” And because Guthrie’s experiences in Oklahoma and Texas formed the ideas that went into his songs, she added with a laugh, “There’s gotta be something in the groundwater there. It’s still there.”

Rather than putting the archives in New York, Chicago or another city that’s got a history of liberalism, she said, it made sense to send them to an ultra-conservative state where discourse, and perhaps understanding and acceptance of different viewpoints and philosophies, needs to grow. The foundation’s offer also was the only one she received, but executive director Ken Levit told the New York Times that he conducted a three-year campaign to earn Nora’s approval.

“It’s a real financial commitment,” she said of operating the archives. “They’re gonna lose money for the first 10 years. The archives are not about making money.”

But part of the reason Oklahoma has come to embrace Guthrie is that he’s good for tourism; as WoodyFest and projects like Mermaid Avenue started attracting more Guthrie fans to Okemah and environs, local business owners gained a new appreciation for their once-scorned native son.

The Kaiser foundation’s efforts to woo Nora included providing at 2010 grant to fund digitization of 76 reel-to-reel tapes in the archives. Their stewardship will allow similar treatment of future acquisitions; ideally, it also will be able to fund data migration to future media and storage formats as they develop.

The family will maintain copyrights to Guthrie’s work; the archives will own only the documents themselves. Nora made another stipulation as well: “I wanted Woody to be street-level, so people walking down the street can look in the window and say ‘Oh, look at that,’ and then walk in. So it’s user friendly.”

Keeping Woody Alive

At the Folk Alliance conference, Santelli moderated a panel titled “The Influences of Woody Guthrie,” with LaFave, Gilkyson and WoodyFest regulars Ellis Paul and Joel Rafael. They talked about Guthrie’s great ability not just to empathize with “the common people,” but to tell their stories as well. But even though his Okie drawl and simple language was more affectation than limitation — as Paul noted, “There was nobody who was more into the mythology of Woody Guthrie that Woody Guthrie” — he also was one of them. He suffered through the Depression and Dust Bowl; he knew hunger and homelessness, even though he wasn’t born into poverty. He also went beyond railing at social injustices in song or on his radio shows or in newspaper columns he wrote for People’s World and the Daily Worker. He stood up for causes he believed in, which, as Gilkyson noted, “Takes an incredible amount of courage.”

During Springsteen’s brilliant SXSW keynote, he spoke at length about Guthrie’s influence on him, noting, “Woody’s world was a world where fatalism was tempered by a practical idealism. It was a world where speaking truth to power wasn’t futile, whatever its outcome.”

He recalled standing in front of the Lincoln Memorial with Seeger — Guthrie’s friend, Almanac Singers bandmate and longtime keeper of his flame — during the freezing weekend of Barack Obama’s inauguration as the first black president of the United States. As they led hundreds of thousands of citizens in singing “This Land Is Your Land” — the once-blacklisted Seeger insisting they do every verse — Springsteen related, “I realized that sometimes things that come from the outside, they make their way in to become a part of the beating heart of the nation.

“When we sung that song, Americans — young and old, black and white, of all religious and political beliefs — were united, for a brief moment, by Woody’s poetry.”

Guthrie and his songs have given us many unifying moments — moments that help us recognize the dignity of the disenfranchised, the evil of inequality, the right of all humans to be treated with respect. And yes, the shared pride of living in a nation of beauty and bounty — covered from California to the New York Island with golden valleys, redwood forests, diamond deserts and wheat fields waving. Even if that country deserves to be chided when it fails to deliver on its promise of liberty and justice for all.

As Nora watched that moment unfold, she finally understood why her father wrote the song. She remembers laughing and crying simultaneously as she tilted her face toward heaven to share the revelation with him.

“The song, Woody, everything was nailed, set in stone forever in history, in that one moment,” she recalled in April. “It was seen around the world by billions of people. And for that moment, this was America — the America of Pete Seeger, Springsteen, Woody and Obama. And I thought, ‘Woah, that’s it.’ Everything else is downhill from there for me. … We’ve been to the mountain, we’ve seen the dream.”

For her, the centennial observances have to be incredibly special to top that. So she questions each proposal carefully. “We’re not interested in the publicity. It’s not about celebrity. We don’t need that. I’m absolutely not interested in that,” she said. “So I stop and I think about it a lot and I go, ‘Why? What can doing something like this bring to the world that the world might want to hear about, or know about or feel good about?’”

The general answer likely lies in something Santelli revealed after the Folk Alliance panel: “Nora, Arlo and I made a pact that we want to make certain to keep Woody’s legacy alive for the next 100 years,” he said, “instead of just reflecting on the last 100.”

It’s great to look back and celebrate the man, he added days after the March Tulsa concert, but it’s just as important to look forward.

“The most important group that’s played our events was probably the Flaming Lips — just to demonstrate how, in the 21st century, it’s cooler to play Woody Guthrie on the iPad,” Santelli marveled. “That taught me something. It reminded me of why we’re celebrating this guy in 2012.”

Gilkyson and activists like Morello, who has been among many artists strumming Guthrie songs at Occupy rallies, might see that connection another way.

“Part of keeping a cultural legacy alive is keeping the movement alive,” said Gilkyson in April. “So keeping Woody’s cultural legacy alive is the same thing as keeping a movement of social conscience alive. It’s about being the best human being you can be.

“Look at him — for all his flaws, he really did put it out there,” she added. “He was very brave and very creative. There’s a lot to celebrate in his life. And a lot to emulate.”

That’s why Morello’s acoustic guitar bears the slogan, “Whatever it takes.” It’s his homage to Guthrie’s famed “This machine kills fascists” labels.

As Guthrie disciple Steve Earle likes to note, it takes a true patriot to question his country’s actions. Or, as Seeger once told a Rock and Roll Hall of Fame & Museum audience, repeating an adage his father told him, “The important question is not ‘Is it good music?’ but ‘What is the music good for?’” The Grammy Museum tried to answer that question with its very first exhibit, titled “Sounds of Conscience, Sounds of Freedom.” Of course, Guthrie was featured prominently.

“Woody Guthrie is the poster boy for all of this,” Santelli said. “If you needed one person to say, ‘Look at his life, look at his musical output, look at his philosophy and his commitment to the common man and working farmer and individual in this country,’ you just need to know about Woody.”

Or, as Dylan once said, if you listen to Woody Guthrie’s songs, you can actually learn how to live.

No Comment