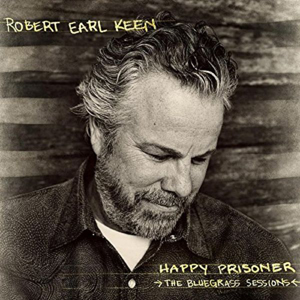

ROBERT EARL KEEN

Happy Prisoner: The Bluegrass Sessions

Dualtone

Forty-odd years and thousands of miles down that road going on forever, Robert Earl Keen’s career has carried him a long, long way from joyriding with his buddy Duckworth in a rust-red 1970 Ford Maverick, getting buzzed on Texas Pride while playing the hell out of Bill Monroe on 8-track cassette. His old College Station band, the Front Porch Boys, are a long time gone, and the songwriting bar he sets for himself these days is a fair bit higher than trying on a lark to stitch together “quite possibly the worst bluegrass song ever written.” And yet, for as long as he’s been making music — building on his rep year after year as one of the most respected (and popular) Texas songwriters and band leaders in the wide world of Americana — Keen has remained, at heart, an unabashed bluegrass fanatic. Because you never forget your first love … or, it seems, the rush of your first youthful pass at “Foggy Mountain Breakdown” and introduction to the narrative spell of a good Appalachian murder ballad.

Happy Prisoner: The Bluegrass Sessions is not an album that was conceived in a record label conference room, let alone one that the average or even biggest Keen fan likely ever would have thought to ask for. Because let’s face it: even putting aside any (irrational) fear of banjos, who in their right mind would’ve ever wagered that a Robert Earl Keen record full of nothing but dusty old bluegrass covers could be anything other than an exercise in artistic folly? Who, indeed, could have fathomed the end result being the best-sounding record he’s ever made? But hearing is believing, and Happy Prisoner is damn near audiophile heaven.

Production wise, this is acoustic wizard Lloyd Maines’ masterpiece: working arguably his best behind-the-boards magic this side of the Dixie Chicks’ exquisitely built Home 13 years ago, he captures not just the warmth, intimacy, and thrilling rush of the band playing right there in the room with the listener, but the wood-and-wire integrity of every note in still-life detail — even when they’re flying fast and furious at the speed of a bluegrass hot-rodded “52 Vincent Black Lightning.” And the fact that Maines is playing but a smattering of those notes himself (by his own recollection, just a little overdubbed slide guitar on Jimmie Rodgers’ “T for Texas”) speaks volumes about the level of talent that’s in that room. In addition to Keen on rhythm guitar and his entire road and studio band of more than a decade (Rich Brotherton on lead guitar, Bill Whitbeck on standup bass, Marty Muse on dobro, and Tom Van Schaik on percussion), Happy Prisoner prominently features the virtuoso chops of bluegrass pros Danny Barnes on banjo, Kym Warner of the Greencards on mandolin, and Sara Watkins of Nickel Creek on fiddle. Noteworthy vocal cameos are also made by genre legend Peter Rowan, singing on “99 Years for One Dark Day” and introducing the cover of his own “Walls of Time,” as well as Lyle Lovett and Natalie Maines, duetting on the aforementioned “T for Texas” and “Wayfaring Stranger,” respectively.

Make no mistake, though: as formidable as that whole A-Team crew is from Maines to Maines, the Happy Prisoner-in-charge and MVP here is most definitely Keen himself. As a singer-songwriter, Keen’s strength has always been heavily weighted to the right side of that rubric (a lop-sided balance that, to be fair, puts him in pretty outstanding company). But given the challenge/freedom to make these songs his own by voice alone, he rises to the occasion with the strongest and most self-assured vocal performances of his career. What’s more, he sounds so comfortable and familiar with the material (most of which he’s probably played to death on every recorded music format of the last half century) that every song here pretty much feels like a Keen original. The album-opening romp through Flatt & Scruggs’ “Hot Corn, Cold Corn” alone is the most riotous fun on a Keen record since the batshit crazy title track of 2003’s Farm Fresh Onions, and he handles the requisite murder ballads and narratives of lonesome woe like “Poor Ellen Smith” and “East Virginia Blues” with the natural ease, empathy and nuance of a born storyteller. And as for the oft-covered “52 Vincent Black Lightning,” well … sure, that old Richard Thompson vehicle may have been ridden into the ground long before the Del McCoury Band even got around to adding it to the bluegrass cannon, but Keen does a hell of a job sprucing it up and giving it his own spin. Which, come to think of it, is hardly a surprise, because who are Red Molly and James if not the prototypes for Keen’s own Sherry and Sonny? — RICHARD SKANSE

No Comment