By Andrew Dansby

April 2003

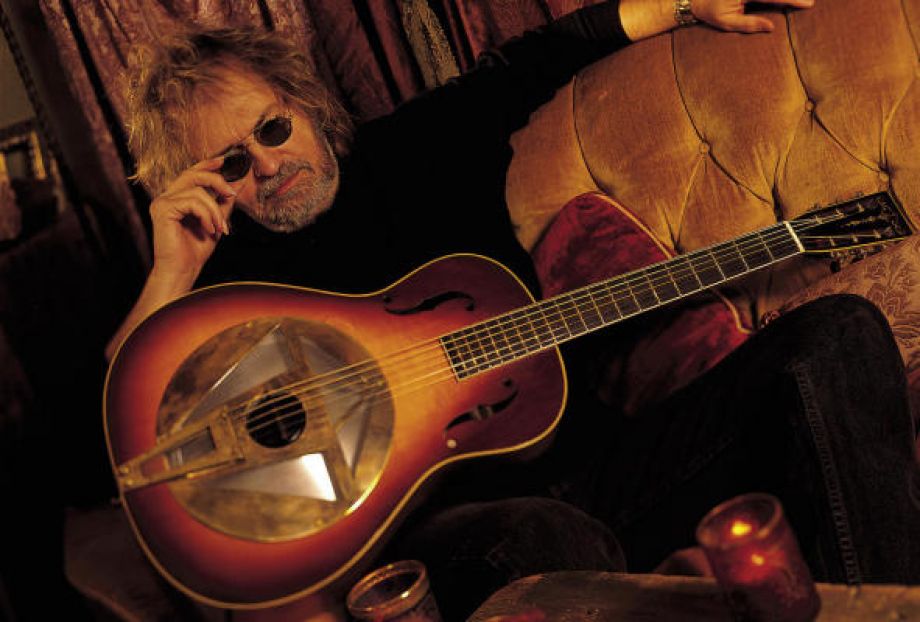

He was born in Oklahoma. But the similarities between Ray Wylie Hubbard and the protagonist in “Up Against the Wall Redneck Mother” — the song that defined him and dogged him for years — end there. The songwriter took to Austin’s ’70 progressive country scene like a fish to a fishbowl. For years he lived the fast-living life of the time, while failing to make much headway creatively and professionally. With the release of Loco Gringo’s Lament in 1994, Hubbard found less confined creative waters in which to swim.

Since Loco Gringo’s, Hubbard has recorded four more albums, each finding him taking creative tangents to what could have been an easier route. On his last, 2001’s Eternal and Lowdown, Hubbard worked in some mandolin and resonator guitar, two instruments that recently piqued his curiosity, in an album that offered a tip to the country bluesmen (Lightnin’ Hopkins and Mance Lipscomb, to name just two), who were regulars in Houston in the ’70s.

The new Growl sounds like the result of Hubbard utilizing the decade of new ingredients he has acquired as a student of songcraft. Some songs are exercises in elliptical efficiency. Others, like “Knives of Spain,” play with the voodoo in assembling a lyric; a song about the alchemy of creating song. The album’s capper is perhaps the best indicator of Hubbard’s fearlessness. The tongue-in-cheek “Screw You, We’re From Texas” can, and likely will, become a calling card for the very people it parodies. It’s a song not unlike “Redneck Mother” in mood (though certainly not in its construction), but at this point in his career, Hubbard isn’t interested in limitations.

You’ve had a pretty fertile period of productivity for the past decade, since Loco Gringo’s Lament.

That’s when I really got serious about my writing and tried to figure out as much as I could about the craft of songwriting. I had albums before that were kind of attempts at writing, but not really understanding a lot about the craft of it. Loco Gringo’s is when I started getting into it and studying songwriting as an art form [laughs], I suppose.

Was there some sort of epiphany that pushed you in that direction?

A couple of things really. I guess at age 42, I started to fingerpick. I read Letters to a Young Poet by [poet Ranier Maria] Rilke. There’s that line in there, to paraphrase it, that our fears are like dragons guarding our most precious treasures. So I overcame this fear of embarrassment, contacted this fellow up in Dallas and asked if he’d teach me how to fingerpick. That and Letters and reading as much as I could about writing and learning how to songwriter, those three things put it all together. I keep trying to learn new things, and that really seems to help. I got a mandolin and learned enough on that to write three or four songs, and lately I’ve gotten into bottleneck slide and open tunings. It keeps doors open.

And you were present for the whole progressive country thing in the ’70s. Several of those guys were obsessed with craft. Did any of that discipline sink in?

At the time I didn’t know that [laughs]. That whole movement, it really was progressive musically. Willie, who had been a country songwriter in Nashville, all of the sudden he got Mickey Raphael, who was a blues harp player, to start playing with him. And Jerry Jeff, who’d been a folk singer, got John Edmond, who was a rock guitar player. And Murphy had been in folk music; all of the sudden he got Herb Steiner to play steel guitar. Musically nobody had been doing it like that. Not to name drop — but I might as well — I still consider myself fortunate when I was younger to have been able to see Lightnin’ Hopkins and Mance Lipscomb and Ernest Tubb and Freddy King perform. I did learn a lot, though I also learned a lot of what not to do [laughs]. But it took me awhile to learn that.

Some people hear the term “folk” and think of Lipscomb or Dock Boggs. Others think of balding protest singers. Do you ever feel uneasy when the term is applied to what you do?

I don’t mind the term. I take it as a compliment. A lot of people I really admire in the past and present are folk singers. But I’m doing things with a band now, I’m playing electric guitar and it still comes back to the music to me. It doesn’t matter what kind of label you put on it, it’s a matter of whether it’s good. There’s certain songwriters where I consider their music important whether they’re done with acoustic guitar or a full tilt band. But I just try to write the best songs I can. Whether they have depth or weight or whether they possess some sense of irony.

Someone once told me that all the hoopla about whether Lightnin’ was playing acoustic or electric was moot. He’d just play the loudest guitar that wasn’t in hock.

One of my favorite quotes, I think it was Howlin’ Wolf that said, “If it’s in the groove, everybody loves it.” [Laughs]. And you go, yeah man. That’s important to me, to be in the groove, whether it’s one guy with an acoustic guitar or a whole band.

Speaking of which, “Name Droppin’“ has a great, deep groove.

It’s working with Gurf Morlix, who is just the guy. I feel fortunate to have worked with Lloyd Maines and Gurf. They do what producers are supposed to do and that’s get the best out of somebody. Right now Gurf’s just working with the type of songs I’m writing. I find myself playing way beyond my capability when I’m with him.

Is there a story behind the album’s title? It’s more primal sounding than your previous titles.

When we started this thing, the key phrase we’d use is “let’s put some growl on it.” Which to us meant to have integrity and play it real. We didn’t want a real clean, slick, overdubbed, pristine album. It was like, let’s play it and not worry about whether the vocals were too rough, as long as we’re in the groove. So [drummer] Rick Richards just made sure everything was really funky and in the groove. It just kind of became our word. Gurf’d grab his guitar and say, “I’m gonna put a little growl on it.”

So where did the phrase “Knives of Spain” originate?

I was watching an old silent movie from sometime in the ’20s. It was A Tale of Two Cities and one of the lines in there was, “his words were as lethal as the knives of Spain.” And I just went Ahhh! That someone’s words can be that deadly. So I just kept that phrase, it always stuck with me. Even if you don’t know what the knives of Spain are, you just figure something like that’s very deadly. So I really just liked the idea: “Make my words as lethal as the knives of Spain.” And that’s how it came to be. The three little verses are a little progression. “If I had poet’s wings,” “if I had a black cat’s bones,” “if I had some grains of faith.” It’s the idea of striving to be a writer. Trying to have the integrity and the voodoo about it.

Some of the songs suggest a stripping away to the barest of songwriting elements. Did you go about “Rooster” and “Little Mama” differently?

I just really enjoy writing like that. “Rooster,” it’s just a little story. You can see this guy — rooster crows at dawn — [he asks] why can’t he do nothing when it’s dark? This guy was just pilfering and he gets shot crawling in a window, gives up his life of crime, picks up a guitar and barely gets home before his rooster crows. It was fun writing it, and I wanted to make it greasy and rural. And “Little Mama” is kind of the same type thing, you see this guy sitting around asking these questions. I took my writing seriously with these songs. When they were basic and raw I wanted to make them lyrically work. But I tried to take myself lightly as I was writing them, not to be too pretentious or deep. Writing is sometimes such a joy and sometimes such an anguish. But this one, I felt like the songs were really coming together right.

Had you done much craps research for “Bones”?

My dad, when I was younger, was kind of a gambler type guy. That’s where I learned the term “Mississippi Flush.” And some of the other terms in the dice game, “Little Joe From Kokomo,” “Fever in the Funk House,” “Eighter from Decatur,” these were terms I heard from dice players shooting craps. So I kind of put in that story thing. You can see the daddy saying, “Let’s go shoot some craps.” 13, 14 year-old kid going with him. And they shoot the gill and come home and said, “We won.” And mama says, “Well I’m just glad.” I think the term my mama actually used was “I’m glad I didn’t have to bury you or get you out of jail.” But I always liked the term “criminal judicious.” [Laughs]. So I wrote that instead. It’s kinda like the “Screw You [We’re From Texas]” thing. I always wanted to rhyme “John the Revelator” and 13th Floor Elevators. For about four or five years, I’ve had that little rhyme somewhere. And finally it ended up somewhere where I could use it. I have these little notebooks with words and phrases and things.

Do you ever grow impatient with what’s in the notebooks? A phrase you can’t stand not to use?

Yeah, but the thing I’ve learned about songwriting the craft is patience. It’s so hard, but you have to just hold onto it. So I just pull out my little book and all of the sudden there it was. But “Bones” you can just see the image of shakin’ them bones. “Baby needs a new pair of shoes,” that’s just what the dice players would say. And we just put it in that funky groove.

I’ve heard Townes Van Zandt was ruthless at cards and dice. Did you ever lose your shirt?

I’ve lost money to Townes [laughs], and considered it an honor. Back in the old days, quite a bit. You know, he was kind of a bar gambler too. If Townes said that he could take a sealed deck of cards and make the Queen of Spades jump up and spit in your ear, don’t bet him, or you’re gonna end up with an earful of spit. A funny Townes story, I think it was him and Wrecks Bell and Mickey [Newbury], they did a recording “Up Against the Wall Redneck Mother” in Pig Latin. I think they actually recorded it under the Hemorrhage Mountain Boys.

That song has been an odd albatross. On one hand it was never really a hit, but at the same time it did become an identifier for you. Do you ever regret writing it?

Nah, since Loco Gringo, I have some credibility as a songwriter that makes it easier with “Redneck Mother,” and for a long time I didn’t. That it was the only song I was known for was kinda rough. But I’ve made peace with it. I usually say, after I write a song, “Can you sing this for 30 years?” Because I wouldn’t have done that with “Redneck Mother.” But it’s like with “Screw You,” I said, “Aw the heck with it.” I have an inner peace about my songwriting. If people get it great, if not, it’s still OK. But you know what’s funny about “Redneck Mother?”

What’s that?

Jerry Jeff cut it I guess about 30 some years ago. And Bobby Bare did it. And the New Riders of the Purple Sage did it. And then there was the Hemorrhage Mountain Boys. I just got a copy last week by Cracker. They sent me a copy, and it’s an incredible record. They do it pretending to be a bunch of drunken fraternity rock guys. They get it. I was just amazed, ’cause I love those guys. They do that and they do Terry Allen’s “Truckload of Art.” Anyway, all of the sudden “Redneck Mother” is cool again.

So was there an initial bug that bit you to become a songwriter?

Well gosh, you’d have to say Dylan. Freewheelin’ and all that stuff. Through him I discovered Woody Guthrie, Cisco Houston and Leadbelly. Murphy went to my high school. He was a senior and I was a sophomore and he had a band. So I decided I needed a band too. And of course, when I was a kid, my grandparents really liked Ernest Tubb. So the big three … [laughs] … Murphy, Dylan and Tubb.

With that 70s scene, there seems to be plenty of romance and regrets. You seem to keep the former in check, do you have any of the latter?

Well, like with “Redneck Mother,” I’ve made peace with it. It was a lot of fun, the ’70s. The ’80s I didn’t particularly care much for. I think Tom Petty was the only one out there fighting disco and what came after. But the late-60s and early-70s, I really enjoyed them. I’m sure my behavior embarrassed and hurt people back then. There’s things I probably wish I hadn’t done, but I don’t have this overpowering need to shut the door on it. I was young and stupid and I know that sounds redundant, but for me I was both [laughs]. I was young and we were in a band. Our [performance] rider pretty much just said, “beer and electricity.” All we needed was a place to plug in and beer and we’d play.

You seemed to take most of the ’80s off. What prompted the silence between your ’70s work and Loco Gringo?

Yeah, well it was hard to write songs when you were just coming-to in different people’s houses [laughs]. It’s hard to concentrate and rhyme lyrics when you’re trying to figure out where you are. The lifestyle got in front of the music. I kind of look back on those days as a period I went through. I don’t really do any of the songs now. I look back on a lot of those songs as pretty amateurish and just kind of stumbling through them trying to learn. I still do “Redneck Mother” because it’s kind of a fun thing to do now with the audience. But through the ’70s, I just couldn’t find out why I couldn’t get a recording career going. And it’s because I was fairly irritating to people [laughs].

Sounds like you picked up some wisdom, at least.

Yeah, I guess so. In those days it was nice to be young. And I was in charge of my own little dark kingdom. I had a funky old bus. And I was in a band, and you’d show up at these honky-tonks and play and drink beer and that’s what you did. But now I try to make it as good as I can, even if it’s a song like “Screw You We’re From Texas.” The lyrics on that, I still think are pretty cool in a way. So I take my songwriting seriously and I try to take myself lightly. And that seems to work better than the other way around. If I try to take myself too seriously, then everything suffers. So I still have incredible amount of fun playing.

Does it ever feel like work to you?

Well, I write these songs and go out and play them, and they give me money and I go home and give it to Judy, and she lets me live here. It’s a great deal. It’s a really good deal [laughs]. It doesn’t seem like work. I guess there’s times, like loading equipment … [Laughs].

No Comment