By Rob Patterson

May 2008

The quick shorthand reference for Mike McClure is that he is the former singer for the Oklahoma country band the Great Divide. But as fans of his know, McClure is far more than that. He is also a prolific and talented songwriter as well as a record producer known for his work with Cross Canadian Ragweed, Jason Boland & the Stragglers and others. In fact, he’s been credited as the spearhead of an Oklahoma music movement that has paralleled the current Texas music movement. Sure, McClure might seem like a good ol’ country boy with a guitar, voice and some songs. But he’s also something of a “Red Dirt Music” rebel, innovator and entrepreneur who is forging what is sure to be a long and distinguished career.

McClure started out with the Great Divide in the early 1990s, playing bars in Stillwater, Okla., home to Oklahoma State University. Thanks to some hard work and two independently released albums, the band became a regional phenomenon and won a deal with Atlantic Records in Nashville, who re-released the band’s Break In The Storm album and another record, Revolutions. Though the band scored a country hit with “Pour Me A Vacation,” when Atlantic’s Nashville operations closed up shop and was merged with Warner Bros. Nashville, the Great Divide returned to being an independent act.

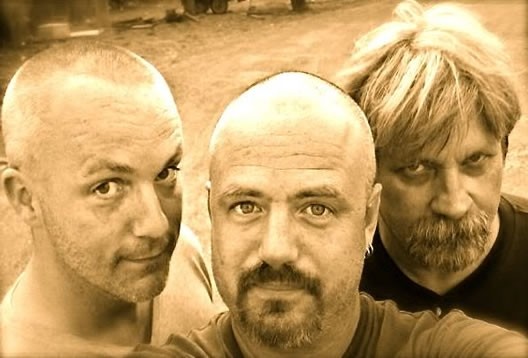

Meanwhile, McClure was starting to record the solo material that became his album Twelve Pieces, and forging his career as a record producer for other acts. Since leaving the Great Divide last year, he has formed the Mike McClure Band and released three EPs and now a 19 song tour de force album, Everything Upside Down. As one of the busiest groups on the live circuit in Oklahoma, Texas and beyond, the Mike McClure Band is becoming a force to be reckoned with. Lone Star Music recently caught up with McClure on his cell phone in the band van on his way to yet another gig.

Texas and Oklahoma have had a long and very close musical relationship. In what ways do you feel the two states are musically similar, and in what ways do you see them as different?

To me they’re kind of hard to separate, because when I first started writing songs, I really got into Jerry Jeff Walker, Robert Earl Keen, Gary P. Nunn, Larry Joe Taylor. I used to drive down to Texas from college on weekends and stuff to go hear music. It really amazed me how open Texans were to original music. And that just really wasn’t so in Oklahoma. So I listened to that music and that really influenced me. And so when [the Great Divide] started playing in Oklahoma, we were starting to kind of develop a crowd, I just really wanted to break into Texas because they just seemed more open to original music. It was kind of unfortunate that we had to get out of our home state to get known. But it’s also nice that we can bring it back to Oklahoma. I think for years people would be from Oklahoma and go up to Nashville and stay because that’s where the music industry is. But I like being from Oklahoma and I’m starting to see some changes where people are more open to original music in Oklahoma now. And I think Texas really influenced Oklahoma in that respect.

I think that Texas music has that swing base. There’s more of a traditional sound coming out of Texas. I think Oklahoma music, for some reason, has a little more of a rock edge to it, at least in this particular genre. And I love rock ’n’ roll. I graduated in 1989, so I was real big into Motley Crue and Van Halen and all that stuff. So that has played a big influence in my music. And then as I got older, I heard things like Jerry Jeff Walker. I really wasn’t listening to country at the time. But those guys made it cool. And I guess I just tried to unconsciously blend that cool country with the rock ’n’ roll that I love.

Was it at all intimidating to leave a successful band and strike out on your own?

I was scared to death. I just felt like it wasn’t making any progress and hadn’t in the past few years. I just felt like there was more to do, and I didn’t think I could do it in the confines of that group. So that’s why I left. Yeah, I was scared to death. I was leaving something I’d done for the past 10 years and helped to build. Jumping out on my own was almost like starting all over again from scratch. It was humbling and also exciting too. It kind of put that fire back in me that I’d been missing, because I got fairly complacent with that band.

Is it important for you to find new challenges?

Oh absolutely. That’s why I started trying my hand at producing outside things. I’m always up for a challenge. I get bored really easy.

Texas music legend Lloyd Maines produced albums for the Great Divide. Was he influential in how you approached producing records for other artists?

Absolutely. I didn’t know anything about making a record until I made a record with Lloyd. And we made three records with him. I didn’t know how it was done. He’s a very patient man and a very good teacher and just an all around good guy. I learned most of what I do from him. He was a very big influence.

What are some of the things you learned from Lloyd?

Tuning. He just drove that into your head. I’d tune once and let it rip all night if it was my way. And just attitude in the studio. He kept it real laid back. I never felt pressured. I would feel pressured from other people I worked with in the studio. I’d go in and not be getting it and then get frustrated and stuff. I learned just that the attitude in the studio is really crucial – making sure that everybody is comfortable so that way they can do their best work. And recognizing that someone is tired and needs a break. Hey, let’s go outside, let’s drink a beer or whatever. That’s what I got the most from him. And also just work ethic as far as keeping the ball rolling. It’s so easy to sit there and go off on a tangent and start trying to make Sgt. Pepper’s. So just work ethic and attitude really. I am eternally grateful to have been able to work with him when I was younger.

Is it true that when you started making Twelve Pieces, you weren’t even thinking of doing a solo album but just recording songs for the sake of getting them down in the studio?

I was in the Great Divide and quite frankly didn’t think I’d be able to put out a record because of contracts and stuff. About the time I started that project was about the time I started thinking that I might want to try this solo thing. As I got it done, I ran out of money, as is the case always. So I had this unfinished project sitting there. And I took what I had and mailed it down to Compadre Records out of Houston. And they said, hey, let’s finish it up and I’ll put it out on my label. Well, that caused a lot of dissension in the band when I did that. But it was something I had to do. I had a piece of work that I wanted people to hear and I wasn’t going to be stifled by that.

You now seem to be taking a fiercely independent approach to releasing your music. Is that a result of what you learned from being on a major label?

Unfortunately we signed with Atlantic at about the time they were going tits up. Of course we didn’t know that; they didn’t tell us that. Then we messed with an independent label. It’s just so frustrating. And their contracts are so in their favor. I can go out and sell 10,000 copies of something I own every bit of it and make more money than if I sold a quarter million records for Atlantic. And if I sold a quarter million records with them they’d tell me that wasn’t enough. Ideally they can help you sell millions of records and generate a lot of money and make a lot of money at your shows. But our deal was that they were pretty much selling our records to our fans and taking the lion’s share of it. I remember calling Lloyd and telling him we were getting a contract with Atlantic. And he said, well, be careful, jumping in bed with the devil. And he was right. But when you’re young, the major record deal is the holy grail, the brass ring you’re reaching for. It’s hard to turn it down. I think I probably could now, just knowing what I’ve been through.

How did you come up with the idea of releasing three EPs and following it with a full album over the last year?

It kind of came out of necessity. We cut four songs and went ahead and mixed them, and then they were just sitting there. While they were sitting there I thought, man, let’s just put a package on this thing and kick it out. I wanted to give this band an identity. Because I was leaving the strong identity of the Great Divide and wanting to do something different and had all this new material. You know, people don’t like to go to shows and hear songs they never heard before, for the most part. People go out to shows for the most part because they hear the songs and they like them and they want to hear them live. So I wanted to get the music out as quickly as possible. So after we put that first one out, we recorded the next bunch of songs. And we thought, let’s stick these out there as an EP. Why not? I never saw anybody do that. So we made this plan. All right, we’re going to release three EPs, and then while those are out there getting familiar we’ll finish up the album and put that out. The record has the stuff from all three EPs plus six more tracks. I didn’t just repackage it so I can resell it. It was just something that came out of necessity. And the cool thing is that those EPs paid for my project. And now that I’ve put out a full length CD, it’s already been paid for, so everything that I make off of it is going to be profit. Usually when you’re record comes out you’re 30 or 40 thousand in the hole. It’s been really good for us. It’s paid for the record and it got the music into people’s hands. And they’re really a bargain too. We sell the EPs at shows for five bucks. And they’ve got a collectors item. Now that we’ve got the album out we’re not going to be putting the EPs out anymore.

How would you describe the difference between the music you made with the Great Divide and what you are doing now?

I just think the Great Divide, especially towards the end, got to the point where we were trying to appeal to mainstream radio and Nashville. I was in there being told how my guitar should sound, and I just didn’t want to play that game. If I wanted to go make a punk rock record, that’s what I’d like to go do. On this album there’s some really country things. And I love country. I just don’t want to be told when I can do it. And they were trying to pick songs that were radio friendly and this and that. And I’m more into making albums. I love the old album format. And most things that come out of Nashville are 10 possibilities for a single, because that’s how they make their money.

Most of this album is just about leaving the Great Divide. So if someone is getting a divorce, this is a good album to listen to. And if you want to just rock out, you can do that too. There’s a lot of different levels going on there.

I know many musicians hate to do so, but how would you describe the music you are now making?

I dunno. That’s really hard to describe. I think my songwriting has a certain voice. And then when I was with the Great Divide it had a certain sound to it. I think it’s the same voice and a different sound. The sound is more me. There’s more of a rock influence and more of a groove influence. I think it’s more of a total package now.

What songwriters inspired and informed your songwriting?

Joe Walsh, Neil Young, Tom Petty, Bob Dylan, Willie Nelson, Van Morrison. That’s probably my upper echelon there. If I write something I try to stack it up against their work. That’s the brass ring for me as far as songwriters go.

So what’s behind the slogan on your website: “Twice As Loud, Half As Popular”?

That was kind of out battle cry there for a while. When I first started on my own, I went from playing for 1,000 or 2,000 people to playing for 100 people. So half as popular was even kind of stretching it. It was kind of a tongue in cheek comment on starting over again. I think those 100 people who came out to see me were into the songs and not just the event of it all. And they knew that I was writing these songs and they sat and they listened. And that’s the best thing anyone can give me — just an ear.

No Comment