By Richard Skanse

May 2007

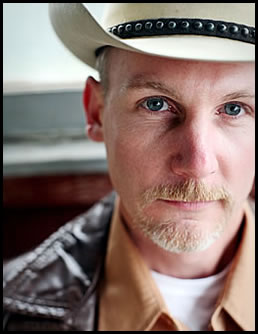

You know those cocky young Texas/Red Dirt songwriter types who look and carry on just like every other ballcap-wearing, Shiner-chugging, high-fiving frat-boy yahoo in a Chili Fest or Billy Bob’s crowd? The kind of guy who could probably steal your girlfriend despite looking a lot like the stereotypical schlubby husband on a CBS sitcom, and probably would steal your girlfriend if he didn’t already have a hotter one or two back on the bus — or maybe a 12-pack and a flask of Crown in their way? Yeah, you do. Well, Max Stalling looks and acts nothing whatsoever like that at all. And not just because he’s damn near tall as Bruce Robison, the Yao Ming of Texas tunesmiths. By seemingly all accounts, he’s just nice as Robison, too. And even though he can pack a dance floor, Stalling’s more of a crooner than a rocker — closer in spirit to an everyman George Strait than a wannabe Waylon. He’s the kind of guy you really wouldn’t mind introducing to your sister, if he wasn’t already engaged. And, well, an Aggie. (Just kidding.)

Yeah, it’s a cliché that’s been beaten into the ground a bit over the course of his career, but Stalling really is the gentleman type. How exactly he’s managed to maintain that after 10 years in the business — based out of Dallas, no less — is a real head-scratcher, but it hasn’t seemed to have hindered him much. From 1997’s Comfort in the Curves to 2000’s Wide Afternoon to 2002’s One of the Ways, he’s maintained and cultivated his own cozy niche in the Texas country scene, and developed into a remarkably fine singer and songwriter for a guy formally trained not in music but rather the finer art of inventing junk food. In an alternate universe somewhere, Stalling’s doppelganger is still hard at work on building an everlasting muffin for Frito-Lay — a gig he quit in this world five years ago. Good thing, too, because it’s taken him all that time to cook up a worthy follow-up to his last studio album, the Robison-produced dandy One of the Ways. For his new Topaz City, Stalling made use of Robison’s brand new, state-of-the-art Premium Recording Service studio in Austin, but enlisted the services of R.S. Field, a noted Nashville maverick who’s other production credits include Billy Joe Shaver, Allison Moorer, Todd Snider and Hayes Carll. Lone Star Music caught up with Stalling to find out what took him so dang long, how he found his way from food labs to honky-tonks in the first place and whether or not his dreams still smell like Fritos.

Good afternoon, Max. You said you’d be calling from East Texas — where, exactly?

I am in a place called Bullard, which is I think about 10 or 12 miles south of Tyler. I just recently started hanging out here.

Hanging? So you don’t actually live in Bullard?

Well, I do for the most part. I just got engaged to [fellow musician] Heather Woodruff, who lives out here. I still have a place in Dallas, where I’ve been living since ’91. We both need a place in Dallas, because my band is based there and her band is based there, too. That’s where my P.O. Box still is and the center of gravity for me. But as much as I live anywhere now, I live in Bullard.

When’s the wedding?

November 9. We’re going to go down to, what’s it called, Puerto Moreles? I didn’t know this, but apparently it’s the hip, cool thing to get married on the Mexican Riviera in November. We’re getting married on a Friday, which I’ve heard is bad luck, but that’s all they had available.

Heather’s name sounds familiar, but … help me out.

She’s a fiddle player who’s played for other people all her career for the most part. But about a year and a half ago, she and her best friend, Andie Kay Joiner, formed a band called Blacktop Gypsy, and they’ve been busy trying to get that project off the ground. But in the meantime, to pay the bills, she continues to pick up gigs with other folks. In fact I’m going with her tonight to Austin, because she’s playing with Bob Schneider at Threadgill’s for his Texas Bluegrass Massacre thing. And she’s also been gigging with Johnny Lee, and she’s done some work with Cory Morrow, Tommy Alverson and Larry Joe Taylor. She’s a really great musician.

So how exactly did the two of you meet?

I have actually known Heather for over 12 years. Her ex-husband, a guy named Woody Woodruff, played in my band. That’s how I first met Heather, years ago. And then we kind of met again on a cruise three years ago; she was playing with Mark David Manders, and I went as myself. Thus, the whole tie-in to the Mexican Riviera — it’s all a big circle.

And a little Fleetwood Mac, too.

Yeah. [Laughs]

Well, congrats on the coming nuptials. And, of course, for getting Topaz City out before the honeymoon. Like all your previous albums, this one’s on the Blind Nello label. You started that with Manders, right?

Yeah. He’s the guy that came up with it first. In fact, he’s the guy that actually got me into the music business. I met him at a honky-tonk in Dallas before I’d ever started playing in public. I was just writing songs and singing them to my ficus tree in my little apartment. But I met him, and he really took me under his wing and kind of drug me kicking and screaming into the music business. So then when I put my first record out, he already had this little label — well, more like an emblem. So that’s how it started.

Where did that name, Blind Nello, come from?

Do you play dominoes? Spades?

Obviously not.

Basically, what blind nello is … you can bid on your hand in dominoes to see who gets to go first in a game. If you bid “nello,” that means that you think you’re not going to be able to catch a single trick with your hand; you think your cards or dominoes are so bad that you’re not going to catch a single trick. And if you bid “blind nello,” that’s kind of a cocky thing — you don’t even look at your cards or dominoes, you just say, “I’m blind nello.” So as far as the music goes, it was just kind of saying, “I know my cards aren’t that good, but I’m going to win anyway!” Again, that was all Manders’ doing. But I love the sentiment of it. I think it does capture the sense of doing things on your own, everything be damned. Even your common sense. It’s about, you know, “I’m going to do this just for the love of doing it. And whatever else happens, that’s good, too.”

You did shop this particular around in Nashville though, didn’t you?

Yeah. A little bit. This record [Topaz City] has been in the making now for over two years; I’ve actually had this thing finished and mastered and in my hands for about nine months. But my radio promoter for the project, Al Moss, seemed to think that this batch of songs had some legs, and he’s turned me onto some different people there. So I shopped it for a while, and I did talk to some small independent labels that were interested and willing to work with me. But quite honestly, when I look at the numbers at the end of the day, I’m more than happy to just do this thing for myself. I think the idea of getting a record deal is kind of the actualization of a dream for a lot of artists, but it just doesn’t feel like it’s quite time for that yet. I still think I can do just as good a job myself as any label could.

How did you end up landing R.S. Field to produce Topaz City?

I shopped it to a bunch of different producers. I talked to Lloyd Maines and Rich Brotherton and Radney Foster and Will Kimbrough. I even tried to suck poor old Rodney Crowell into it. Then I got to talking to Brad Turcotte at Compadre Records in Houston, and he told me about Hayes Carll’s experience working with R.S. on his last record. So I called Hayes, Hayes gave me his number, put in a word for me, and R.S. and I started corresponding. He came to Dallas and I introduced him to the band, and I really just loved him. He is an amazing dictionary of American music history — and one of the funniest people I’ve ever met in my whole life.

Bruce Robison produced your last album, One of the Ways. How did that experience compare to working with R.S.?

When Bruce and I got together on that project, he told me, “Look, I’m trying to build a studio. And I’d love to work on your project, but I’ve never produced a record front to back. So there’s going to be a lot of feeling our way along.” His new studio is pretty swanky, but at the time we made that record he was still working out of a little poker shack behind his house — just an itty bitty little place about the size of a living room. So I didn’t know what to expect going in. Being that he’s one of my all time favorite songwriters, I figured it’d be a lot of him telling me to change a lyric here or something like that. But he didn’t get into those details. He really focused more on the sonics of the project. I don’t know if many people know this about Bruce, but he’s a real gearhead. He’s very technically adept, and he knows everything … he knows, like, what kind of microphones they were using on all the old Sun records. And what kind of patch cables they were using, what board they used — stuff that was way over my head. He knows that stuff inside and out.

And R.S.?

R.S. is also a gearhead. But he’s not afraid, not one of those guys who’s going to say, “You can only use 2-inch tape, there’s only one way to do it and everything else sucks.” Which I think is one of the beauties of Bruce’s new studio, because it’s a marriage of old and new technology. Bruce has a natural reverb chamber built in, but he also has all the latest software and things like that. He’s picked what he believes to be the best of the best and married the old technology with the new technology. So that was right in R.S.’s wheelhouse; he’s all about that, too.

How far do you and Bruce go back? Was that last record the first time you ever worked together on anything?

Yeah, that was the first time. I’d always been a huge Bruce Robison fan — so much so that I was kind of intimidated to even approach him at first to produce the last record. I think I finally just got a number from somebody and called him up. Ironically, he and Charlie were out touring together, and had a show coming up at Bass Concert Hall. And separately and apart, I got asked to open it. So I called him and told him who I was, that I was going to be opening the show and wanted to talk to him about producing my record. So it just kind of serendipitously worked out.

I gotta bet the two of you got some real funny looks from people anytime the two of you went out in public. It’d be hard for the two of you to blend into a crowd.

Yeah. People look at us like we’re part of a basketball team or something. And Bruce has got a couple of inches on me.

So tell me about the title track on this record. Where exactly is Topaz City? Is that Topaz, Utah, or Topaz, California?

It’s actually a fictional place. I’m from a town called Crystal City, Texas. When I started writing the song, the original lyrics had “Crystal City” in them. But I’ve kind of been chided in the past for being a little too regional or geo-specific, so I made a conscious effort to try and change the names to protect the innocent. I wanted it to sound like it could be anybody’s hometown. So I did a little research, and as far as I know, there is no Topaz City anywhere in the United States. There’s a Topaz or two, but no Topaz City. But there is an O’Henry story that references a Topaz City — it’s about this guy from a Topaz City in Arizona, living in New York, and it talks about the plus and minuses of the big city verses a small town.

So that’s where you got it from.

Well, I kinda got a little too clever on this deal. See, I tried all these different words to get away from “Crystal.” Crystal is real clear, you can see through it, so I wanted some kind of a gemstone that was glass-like, but maybe not as clear as crystal. It’s a little hoaky, but that’s really where it came from. I finally settled on Topaz as opposed to amber or whatever.

Gotcha. So it’s kind of like you saying, “I’ve got this friend named, um, Mark Stallinger ..”

[Laughs] Exactly! Sure, that’s a good reference. But really, I’m not ashamed of where I’m from by any means — I just wanted the record to be able to transcend Texas or Oklahoma.

I know it’s kind of a silly song, but the real standout for me on the record is “Ping, Pong, Pool.” That just sounds like the kind of song you’d like to leave on George Strait’s doorstep, and then step back and wait for the checks to hit.

Thank you. Well, hey, brother, any of my songs you want to leave on George Strait’s doorstep, you’re in!

You might have to talk to Bruce for help on that one.

No doubt. He’s the go-to guy for that stuff. But yeah, that song … it’s such a simple chord progression, but oddly, that one took me a long time to write. I mean, that one took like four years to find all the little references that I wanted to stick in there. And like you said, it’s such a silly song, why would I invest so much time in it? But I had that first verse, and then I just couldn’t come up with the other principles for the other vignettes. In fact, and this is going to sound really dumb, but I wanted to cook a whole meal. A different course for each chorus. I started with the marmalade, and then I did fried chicken, but I wanted to do biscuits or something at the end, too. But I’ll be honest with you, it was just too much work! I just gave up. I figured three choruses was enough.

Four years? It sounds like your opus.

Maybe. But God, I hope that’s not what I’m leaving as my opus!

Which ones are most proud of on this album? Were there any that made you think, “Dangit, if that ain’t a hit song, then I don’t know what!”

Yeah. I really think the second track — “Never Need to Fall in Love Again” — that song came together in like a day and a half. And for me, those are always the ones that seem to do okay. I think it’s a simple enough song and a universal enough song that people should be able to relate to it. But at the same time, at this point, I’ve kind of given up on trying to figure out people’s likes and dislikes. I have no idea when it comes to what people will think sounds like a hit, because I never seem to be able to put my finger on it. I’ve never been a very good DJ, I can tell you that. I can remember going to parties in high school and putting on songs that I wanted to hear, thinking, “Man, these are great songs!” And everybody else would be like, “Hey man, get away from there! Let JoJo handle the DJ stuff — you’re bringing us down, playing that really gay, goofy stuff.” [Laughs]

Was “Never Need to Fall in Love Again” written about your engagement?

It really was. That definitely is one that’s pretty heart-on-the-sleeve and true-to-life.

Another one that stood out for me is “Lonely Days.” I just really like the melody on that one. Was that another one that took like, 10 years, or was that one of the quicker ones?

It didn’t take 10 years, but it did take me a while. You have to understand something about me: I’m a pretty lazy writer. I don’t sit down and go, “come to me!” and really grind at it. I might do that two or three times a year. The rest of the time, writing is just kind of a constant … anytime I’m driving, or using the weed-eater or whatever it is I’m doing, laying in bed trying to go to sleep at night, I’ll try and noodle through these things. So I just kind of wait for them to drift in. I’m pretty lazy. That’s why some of these things take four, five, six years to finalize themselves.

You really have kind of spaced out your albums over the years. You’re not an album-a-year kinda guy.

No. There were a lot of factors though that played into why this one took so long. I mean, it’ll be five years in September since the last time I had a studio record out. I had a live record out last year, but I don’t think those really count. But there was a bunch of stuff that happened both business-wise and in my personal life that slowed me down. The main thing on the business side was when Southwest Wholesale [a distributor based in Houston that catered to lots of artists on the regional scene] tanked, I just really didn’t have the wherewithal to make another record, quite honestly. And then there was stuff happening in my personal life to where I was just happy to be touring and gigging. But shockingly enough, for whatever reason, my crowds have continued to grow all this time even without a new record out.

When Southwest Wholesale closed down — that was right after you’d left your corporate gig at Frito-Lay, right?

Yeah. I left the Frito-Lay gig the year that I put the last record out — I left in the first of ’02, made the record with Bruce and then put it out in late ’02. And then in February, Southwest went belly-up. And I thought, “Uh-oh, maybe that wasn’t such a wise choice.” But somehow, it’s all worked out. I guess everything happens for a reason.

You mentioned being a big fan of Bruce. Who are some of your other touchstones as a songwriter?

One group of guys that I always mention, I call them the Three Jims: Jimmy Buffett, James Taylor and Jim Croce. I grew up listening to Croce — my sisters and my brothers had his records, and he was all over the radio in the ’70s when I was a little kid. I just loved his melodies and his stories. And James Taylor, I loved all of his major hits. They were in constant rotation in my house, too. I didn’t really get to know Buffett’s stuff until my college days and later when I got to Dallas. He gets kind of a bad rap for his more commercial stuff like “Cheeseburgers in Paradise,” but when you go back and look at his catalog and listen to records like Changes in Latitudes, Changes in Attitudes, and Living and Dying in 3/4 Time, there’s some really kick-ass songs on those records. Really well-crafted and very unique; he approached things in ways that I’d never heard before.

Other than those three, I mainly listened to rock in high school: AC/DC, Judas Priest, Boston, even some ELO. But then I came to College Station and started getting back to my country roots: David Allan Coe, things like that. And I would have to say — and I know you can’t swing a dead cat without hitting some guitar-picker in Texas who says he was influenced by Robert Earl Keen, but it would be disingenuous of me to say anything else. I mean, he was just kind of moving from that stage of playing 200-seat rooms to starting to play the Majestic Theater. Things were really blowing up for him at that point. And yet he still seemed really approachable. I just really related to the songs that he sang. He’s never been cornered as a great vocalist, and I think that gives a lot of people hope! So he was a big influence, just in terms of even getting into the business. I don’t know that I ever really patterned my songs on his, but he really was an inspiration. And like I say, I know every frat boy with a guitar within a thousand miles is going to say the same thing, but that’s the fact.

No, you’re just showing your age — these days every frat boy with a guitar within a thousand miles cites Pat Green or Randy Rogers. You’re old-school.

Yeah. Those guys are a whole new generation. But we all stand on the shoulders of giants — it’s not like there wasn’t Guy Clark and Townes Van Zandt and Steve Earle and all those other people before Keen.

How old are you?

Do I have to say? I’m 40. I graduated high school in 85, then got out of A&M in 89, but I wasn’t ready to face the world yet so I stuck around and got another degree from A&M. I got a masters degree.

Did you grow up in an Aggie family?

I did.

So you had no choice in the matter, did you?

I had no choice. Well, actually, my dad said I could go to any school I wanted to, but he was going to be sending checks to College Station.

You got a degree in food science. How does one hit upon that path?

Because I didn’t know what else I wanted to do. And I had two sisters who were in food science. I was general studies for a couple of years, until finally my counselor was like, “Dude, you’ve got to pick something.” So I picked food science. And it was in the college of agriculture, which was comfortable to me — I understood those people there. But it was really for lack of anywhere else to go.

Did you ever think of music as a profession while growing up?

Noooo. I didn’t even pick up a guitar until I was in grad school. I’d never written a song until I was just getting out of graduate school. It never even crossed my mind until a couple of years after I got up to Dallas. I feel bad, because at the time that I was there, Lyle Lovett was coming into town, playing over in Bryan. And Townes was coming through, and Uncle Walt’s Band — there was a lot of great stuff happening, but I missed the opportunity to see a lot of that stuff up close and personal due to ignorance.

Once you moved to Dallas, you got your start hanging out at the Three Teardrops Tavern. How did you fall into that scene?

When I first got to Dallas, I was totally miserable and didn’t know anybody. I was totally lost. But I was scanning the radio dial and found a community station called KNON. They have a two-hour show on weekdays that they used to call the “Super Rope a Redneck Revue.” They were playing Robert Earl Keen and Townes Van Zandt and Guy Clark and Hot Rize and Commander Cody and all these cool bands that I’d never even heard of, and I just gravitated to it. And they kept talking about this place called the Three Teardrops Tavern, so I started going and I became a regular. And that’s where I met everybody in the North Texas scene: Matt Hilliard from Eleven Hundred Springs, Tommy Alverson, Larry Joe Taylor, Joe Pat Hennan, Ed Burleson, Mark David Manders … blah, blah, blah.

But you still had a few years ahead of you working at Frito-Lay. What exactly did you do there?

I was a product development scientist. I basically did research and development on new snack food products.

What’s your claim to fame in that department?

My claim to fame? Most of the stuff I did either went to market for a very short time, or … well, actually there’s one product I did that’s out there called Snack ‘Ems. But I think it’s actually under Quaker at this point. They’re these kind of sweet, salty little crisp; kind of halfway between a chip and a cracker, but kind of sweet flavored. I actually never had one until recently.

What do you mean you never had one? What did you do, just sketch these things out on a computer or something?

No, I mean I never had one after they went to market until recently. Some of that stuff takes years to get to market. It may take four, five, six years before a product gets perfected and the marketing people think it has a space out there on the shelf. So I never really had any of the finished product. But I worked on it for a year and a half, trying to tweak it out and to find it a home under all the different brands that Frito-Lay had.

When I first came to Frito-Lay, I was hired specifically to work on a muffin project. They had a joint venture with Sara Lee, and they wanted to come up with some muffins that would last 45 or 50 days on the shelf. So I was brought in to work on that stuff. They had a whole line of sweet goods — cupcakes and cookies and muffins and strudels — but my part of the deal was the muffins. But the whole line never did go to market. They finally decided it just wasn’t going to work.

All these years later, do you ever still wake up in the middle of the night with a new snack idea?

All. The. Time. [Laughs]. All the time. And my band, of course, is full of brilliant snack ideas. Every day they hop in the van with a new one, like beef jerky bubble gum. I can’t even begin to tell you all the things that we’ve come up with.

No Comment