By Richard Skanse

“Today is the day our record is released into this strange, alternate universe that we’re living in right now where I can’t tour …”

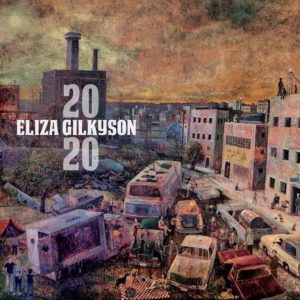

Under more ideal circumstances, Eliza Gilkyson undoubtedly would have opted to celebrate the launch of her latest record, 2020, at a different venue — pretty much any venue — other than her garage.

Eliza Gilkyson picks a different theme for each of her weekly quarantine live-streams (Fridays on Facebook at 5:30).

Don’t take that the wrong way. Like countless other artists sequestered in the time of COVID-19, Gilkyson has dutifully learned to make lemonade out of quarantine lemons and a decent wifi connection; and as makeshift performance spaces go, that garage — or at least the tapestry-decorated corner of it that she allows on camera — ain’t shabby. With lighting and mixing assistance from her son and producer, Cisco Ryder Gilliland, her live-streaming set-up is a fair sight (and sound) better than most, and she’s embraced her Friday night broadcasts on Facebook as an opportunity not just to stay connected with her audience, but to deep dive into her catalog for thoughtfully curated theme sets: e.g., “Songs of Comfort and Consolation,” “Songs for the Earth,” “Love’s Shadow,” etc.) She’s not singing to digital crickets, either. To date, every one of her “ELIZALIVE” episodes has been watched in real time by hundreds of fans around the world: far more, at least per show, than could ever be accommodated by most of the prestige listening rooms and even some of the smaller theaters she normally plays when she can tour.

And yet, still … there was just something about her April 10 live-stream, showcasing songs from her released-that-same-day brand new album, that underscored both the limits of the medium itself and an unintentional irony baked right into 2020’s title. Because if ever there was an album not made for a time of social distancing, it’s this one.

“I was really hoping that we’d be marching together and singing these songs together at shows,” a resigned but resilient Gilkyson told her online viewers at the outset. More than just an after-the-fact hope, though, she explained that it was actually her intent behind writing those songs and making the album in the first place. Inspired by “the great tradition of Seeger and the old-school folk movement,” her aim was to help like-minded souls find courage through solidarity in the fateful run up to the 2020 election. And you can hear that sense of purpose running throughout the entire record, from the opening call to action of “Promises to Keep” (“I’ve been counting on my angel choir / to put some wings upon my feet / Fill me up with inspiration’s fire / And get me out into the street”) straight to the closing affirmation of “We Are Not Alone”: “We are conjuring our forces / And coming face to face with every fear / But there is comfort in our voices / reminding us of all that we hold dear.”

As for which side of the political divide Gilkyson is standing on when she sings of and for “we,” rest assured it’s not the one that’s spent the last four years trampling civil rights under foot and locking children in cages at the border, to mention just two of the horrors referenced in the album’s “My Heart Aches.” Other clues, as if needed, abound: The sing-along anthem “Peace in Our Hearts” marches its defiance right up “into the face of the hateful mind,” and the fearsome “Sooner or Later,” heralding a day of reckoning for those abusing power at the expense of both the people and the planet, cracks like ominous thunder just before the apocalyptic cleansing of Dylan’s “A Hard Rain’s A-Gonna Fall.” And just for good measure, there’s even a Woody Guthrie song about a Trump — or rather, a brand new Gilkyson song adapted from a letter Guthrie addressed in 1952 to Beach Haven, a segregated apartment building owned by the notorious landlord Fred Trump, Donald’s dad.

Of course, this isn’t the first time that Gilkyson has looked to Guthrie and his generation for inspiration. Her father, the late Terry Gilkyson, was a contemporary of Guthrie’s who sang with the Weavers in the early ’50s and later led his own folk band, the Easy Riders, before taking his songwriting talents to Disney in the ’60s. Eliza, born and raised in California, released her own first album in 1969, at age 19, and went on to record prolifically throughout the ’80s and ’90s. But it wasn’t until the release of her watershed Hard Times in Babylon album 20 years ago that the by-then Austin-based singer-songwriter really hit her stride. Since then she’s been nominated for two Grammys and earned many times over her sterling reputation as a critically and peer-revered paragon of modern American folk music. And as a conscientious crusader from the school of WWWD (What Would Woody Do?), she flies that folk flag higher than ever here in the year 2020, despite the trend toward favoring the more contemporary, hipper handle of “Americana” or even the catch-all “singer-songwriter.”

“I am proud of my folk music heritage and roots,” she wrote on her Facebook page earlier this week, echoing the come-together message at the heart of her new record. “And yes, I’m a sap for ‘us’ and all that we dream of and work towards, and even if we never reach our goal, we had a lot of fun on the way, we got to have a chair in a wonderful circle of dreamers who made sure we had food and a roof over our heads, and who lustily sang along with us. And yes, which side are you on? It’s a damn good question. Sing it loud. Don’t be afraid. Don’t be embarrassed. You’re a folksinger damnit!”

I caught up with that proud folk singer — via phone, of course — in early April: three weeks into quarantine, two days before the release of 2020, and the morning after the passing of John Prine from COVID-19.

So, normally I’d start a phone interview with a standard “where are you talking to me from,” but that seems like a particularly dumb question these days.

[Laughs] Well, I’m at home in Austin, but it’s still a fair question to ask of me, because I usually spend part of the year in Taos. And believe me, we keep looking at Taos and thinking, “Do we need to escape from Monster Island?” But there’s really no place to run, so we’re going to hang in here in Austin. We’re in the age group where you’re really supposed to stay home and not do anything, so that’s what we’re doing. I think in the last three weeks, we’ve gone to the market twice, and that’s it.

I know I’m probably not the first person to bring this up, but what could be more “2020” than 2020 throwing a global pandemic into the picture right before you release an album actually called 2020?

Who knew, right? I knew I really wanted to make this for the election year, because I think this is such a pivotal, critical year in the history of our nation and the history of the earth itself. So I thought it should be named that. But of course I didn’t know what that was going to mean at the time, though. It just keeps getting more intense.

And the hits keep coming. Yesterday we lost John Prine. And I’m sure it wasn’t lost on you that we had a super moon last night, just like the one on the night of the 2016 presidential election that you wrote about in “Lifelines,” on your last album, Secularia: “All of these like minds reel from this blow to the heart / turn to each other on the night of the super moon.”

Yeah. Super moon to super moon. That’s basically what we just did: 2016 election, super moon, and now here we are, with the death of John Prine and … end times. It makes it hard not to see this as just something that’s happening that is so beyond our control that it’s just cyclical; that’s it’s the nature of things. And you can’t stop it. You have to just get up every day and hope for the best, because otherwise, you won’t get up.

Did you know John, personally?

You know, I was telling my husband last night about how a lot of people in our genre knew him well, but I did not. I opened for him several times, and he was incredibly sweet to me and very supportive, but we weren’t friends. So I’m just like everybody else: as a musical person, I feel a big hole, and I feel the collective sorrow of what we’ve lost, a role model for artists and for human beings. But he was somebody that I loved from afar.

When did you first open for him? Was that after Hard Times in Babylon?

Oh, no. It was very long ago; I would have to say late ’70s probably, because I was still “Lisa” Gilkyson then — I hadn’t claimed my real name yet. But it’s actually a really sweet story. I was living in Santa Fe, and I got a gig opening for him in Alamosa, Colorado. And I expected nothing, because as usual, I’m always under the radar: nobody knows who the fuck I am, and I was so young really, just starting out. But I opened for him, and it turned out that he and his band heard me, and they came out and watched my opening set. And when I came backstage afterwards, they all came over to my dressing room. John and his band all brought their guitars and they serenaded me. It was like they were honoring me, like they recognized me as a comrade. And it was so touching that I never forgot it.

This is a tangent, and I’ll come back to 2020 in a minute, but … I knew you used to go by Lisa Gilkyson. I actually found a copy of your 1979 album From the Heart, which you released under that name. But I’ve never heard you talk before about how changing to Eliza was you claiming your “real name.” What was behind that?

Well, I was born Eliza, which is an old family name; on both sides of my family there are Elizas. But I guess my parents kind of thought that wasn’t a very classic American ’50s name, so they called me Lisa. And I was Lisa the whole time I was growing up — I didn’t claim Eliza until I was in my 30s. It was at a point where I really wanted to distinguish myself. And it was actually hard to change back to my real name, because I had really identified with Lisa for so long. My brother and sister were very kind about it, but my dad was kind of annoyed that I asked him to call me Eliza, and my friends all had to practice it for about a year before it took. And there were times when I thought it seemed kind of phony, and I felt like, “I can’t keep asking people to do this for me …” But I’m really grateful that everyone did, because now I look back at “Lisa” and I think, “Oh my god, who was that person?” I’ve evolved so much since changing to “Eliza” in my 30s, and that was almost 40 years ago! So I’ve been Eliza now for most of my life.

Once you got through that initial awkwardness, did reclaiming that name feel empowering?

Oh it was very empowering. In part because it’s an unusual name; you see more of them now, but back then, there was nobody with that name. But it also gave me an opportunity to sort of claim an identity, and also in a way, reinvent myself. But reinvent myself maybe based on who I really am. Because up to that point, I was trying all these different hats on musically, just trying to figure out who I was. And being able to claim my honest name was a big part of finding myself.

Well I’m glad it stuck. But — transition! — it really sucks that, right now, you’re finding yourself literally stuck at home, just as you’re releasing this record that’s all about feeling called to action with “promises to keep” and …

“Get me out into the street!” Right. And now we can’t even do that! It’s so freaky.

But it’s unfortunately par for the course of late. It seems like, at least if you’re on the left, the last three and a half years have been defined by this recurring pattern of surges of hope that inevitably run smack into a wall. From the 2016 election to the Texas senate race in 2018 to the Kavanaugh hearing to any number of things since, it’s been just blow after blow after blow.

I know. And that was what I wanted to address, the emotional roller coaster ride. I wanted to write about the extreme feeling of this time period. There’s so much grief around it, and then of course there’s the anger, and the dashed hopes and the determination to continue — 20 times a day we’re going through this stuff. And you want to just go deep into the cave and lick your wounds, but we have to just keep showing up. And that’s what I really wanted to tap into on this record, rather than just, “Here’s this political stance I want to take, here are the hierarchical powers that I’m fighting, etc.” It wasn’t going to be about that. It was going to be more about, “What can I do to rally the troops?”

Was that rallying spirit tangible in the studio? You brought the songs, of course, but did it feel like everyone playing on the album shared that same sense of purpose?

Yeah. Well, one thing that Cisco did that I think in hindsight was prescient, was he wanted me to go into the studio with a band to cut this. And I hadn’t done that in years. I usually cut to click with my guitar, and I sort of work a lot of stuff out by myself, and then we add layers, piece by piece. But Cisco really wanted a band feel this time, so there was a real sense of solidarity. And I mean, when you’re working with players like Chris Maresh and Bukka Allen and Mike Hardwick and Cisco, there is a real sense of purpose and determination, just because of the kind of players they are. Everybody knew exactly what we were doing and what the music was about.

Did you bring all of the harmony singers in at the same time as the band, too?

No, they all came later, but we did get them all at once. The call went out to the WEWIM (“Women Elevating Women in Music”) group here in Austin, and they all came in together. And everybody had to bring their own headphones, because we didn’t have enough! We had to run a lot of cables from the control room, because in Cisco’s studio, we’d only ever cut one or two things at a time. We’ve never done a big group like this before. So that was challenging but fun, and we had a lot of laughs. And it was also really neat because my granddaughter (Bellarosa Castillo) joined us, too — that was the first time she’s sung with me on a record.

There’s a line in the opening song, “Promises to Keep,” that could be read two different ways: “We’re on fire / on fire / we’re on fire now.” I assume that means “we” as in a movement, rather than “the whole country or world’s on fire” — or did you mean both?

It was both: the troops are on fire and motivated, and the world’s on fire. I actually wrote it in a hotel room while Australia was burning, so it was literal. But it was really more about the collective “we” as in a bunch of us, saying, “get me out into the streets!” And that was one of the really important points that I tried to focus on in this record: singing to the choir, to get us all on the same page. Because you know, we’re very, very disjointed and not unified right now, and we don’t stand a chance if we’re not together in these next steps for the next six months.

When people use the term “preaching to the choir,” it usually implies that you’re wasting your time instead of trying to reach the unconverted. But in this case getting everyone in the choir not just all on the same page but inspired really is the priority.

Oh my god, the choir is really demoralized right now! And it’s so split. There’s so many disparate points of view, I have to preach to the choir. I mean, there’s nothing you can do anymore to turn the minds or the mental set of the right wing; they’re going to ride this thing to hell. So I have nothing to say there and there’s no argument to be made, because they drank the Kool-Aid. But we — as in the rest of us — need to get our shit together and come together with a real sense of unity and purpose. Because we’re running out of time.

But as urgent as your message is here, there seems to be element of, if not quite restraint, then at least an almost “zen” calmness to it. When you first announced on Facebook that you were making an album to be called 2020, and noted that it was obviously going to be very political, I’m sure I wasn’t the only one who was expecting to hear 10 or so brand new songs as furious as “Man of God,” which you wrote in reaction to the Bush administration and the war 15 years ago. But that’s not what this turned out to be at all. There are flashes of that kind of fury, like in “Sooner or Later,” but the main message is far more “Peace in Our Hearts.”

Yeah. Because you’ve got to pick what it is that the collective needs at any one time. And you know, “Man of God” was more about really channeling the anger and the outrage of it all, but we’ve walked a lot of miles since those songs. Things are so much more complex now. And I think we’ve really got to find in ourselves, as individuals and as a collective, the common thing that unites us now, which is a sense of wanting our agenda to be the agenda, to be the ways that the poles shift. And we need to decide, what is our agenda? Is it that we’re just so fucking pissed off that we’re going to tear the building down? Or is it that we’re going to call on the better angels of human nature to fight this battle? So I think that’s why I went in this direction of, “What is the unifying principle?” And that’s “peace in our hearts.” It’s got to be that.

I feel like that also speaks to the fact that you’re writing now in response to a very different kind of threat. You’re not singing so much about taking on the archetypical “masters of war” again as you are about a fight for the soul of America.

That’s right. You fight for the soul differently than you do for or in the political arena. That’s really true. It comes down to the soul. We’ve lost so many rights, and now it really comes down to moral and ethical choices.

Did you have to pull yourself back any? Were there songs that were more venomous that you decided just didn’t fit the message, where you were like, “No, I’m not going to go that way,” or did they all just naturally fall in line?

Well, you can’t really control what comes out when you’re writing; you don’t want to control it, you just want to let it come out. But I did have a kind of agenda in wanting to write songs that people would sing, that they would just want to burst into song and sing with me. So you know, singing “with peace in our hearts” over and over again, or even “sooner or later.” Even though that one [“Sooner or Later”] is venomous, it’s also saying, “When is this going to happen, and how is it going to happen, if we take this back?” So it is more of a complex time. But in order for people to sing along, I had to come up with very simple and really fairly positive thought forms. Well, I don’t know if they’re all positive, but they are sing-alongable and simple.

It’s interesting that even in “Beach Haven,” the song you wrote by adapting a letter Woody Guthrie wrote to his landlord, Fred Trump, the message isn’t “Let’s pull the bastard down out of his tower and drag him into the street!” It’s a utopian dream of, “Imagine how beautiful this place could be if we could all just sing and work and play together.”

Right. And I think that’s the message we need right now: “Imagine how beautiful it could be.” And that’s what I was doing with my song, “Beautiful World of Mine,” too. It’s like, “oh my god, yes, it’s awful, it’s fucked — but this is how beautiful it really is.” It compels me to want to dedicate my life to this beauty, and to this vision. And I think that purpose, that arrow, can strike more true than any other approach.

You’ve got a song each on this album by Woody Guthrie, Pete Seeger (“Where Have All the Flowers Gone”), and Bob Dylan (“A Hard Rain’s A-Gonna Fall”). That’s quite the folk trifecta.

Yeah. And I really thought about it, too, because I know right now that’s sort of … “Okay, boomer.” [Laughs] So Cisco and I talked a lot about how, with that mentality that the boomer era is sort of in the past, do we — do I — really want to do this? Is it just retro? But then I thought, no, it’s not. Because folk music has always been political, and it’s always been about people singing together. And so it just seemed really important to me acknowledge those folk roots, and Seeger, Guthrie, and Dylan are the foundation of urban political folk music.

It’s fitting that you mention that “okay, boomer” mentality, because it kind of leads right into a question I wanted to ask about your father and his reaction, as part of the pre-boomer folk era, to the music of your generation — or specifically to Dylan. There’s the whole popular narrative of Bob Dylan hitting the folk scene of the early ’60s like a meteor, even before he went electric, and sort of wiping out a lot of the dinosaurs. And because your dad came from that generation before Dylan … do you know or remember if he felt threatened?

I think my dad really could see the end of his youthfulness, or — what is the word? — his relevance. I think when the ’60s hit, and certainly by like ’67, ’68, I think my dad saw his whole thing, his genre, waning. He saw that his time was up, and he kind of bailed at that point. He really stopped producing. So I think that does happen. But then you look at Pete continuing on forever and staying relevant, and of course Guthrie never lost relevance; even though he died so many years ago, he’s continually being reinvented. So I think if you dig deep enough for the humanitarian roots behind political folk music, you’ll always mine the archetypical vein and you’ll find the thing that runs true through generations.

Well, yeah, but do you remember if your dad ever expressed his opinion of Dylan in particular, as one songwriter reading another?

You know, I think he “got” it. I don’t think he totally got Dylan’s voice, but … well, I don’t actually remember him saying anything specifically about Dylan to me. But I do remember one time, we were driving somewhere in my dad’s VW van, and we were listening to “A Day in the Life,” which had just been released. And my brother and I were both so excited by the ending of it. Remember how it ended, where it would build and build and then hit that big crescendo? My dad had kind of turned the radio down, but when it got to that end part, either my brother or I — I can’t remember who — reached over and just cranked it up. And we were both like, “THIS is what’s happening!” And our dad just looked us like, you know … [Laughs] Of course he was very musical himself, so he understood that musically it was interesting. But I think he also saw that it was the death knell for what he did.

Do you remember the first time you heard Dylan’s “A Hard Rain’s A-Gonna Fall”? I guess you would have been about 13 when it first came out. Did it hit you right away, or not until sometime later?

I can’t really remember when I heard it first. Did Joan Baez do that one? I can’t remember if she did or not. But yeah, it definitely hit me. Because I’ve always been apocalyptic. I have! If you look at the stuff I was writing in 1968, I could see the end of this cycle even back then: I don’t know about the end of everything, but I certainly could see the end of this system as we knew it. I guess somewhere real early I just understood that we couldn’t go on the way we were going. So Dylan’s apocalyptic stuff always resonated with me. “Jokerman” is another one of his that I’ve done. And for the most part, over the years, I’ve had to tamp down my apocalyptic, end-times tendencies. I’d only allow myself one or two per record. [Laughs]

So exactly how apocalyptic are you feeling right now, four months into 2020 and seven months from the election, with everyone under quarantine? Or to try to put it in a more optimistic way, on a scale of 1 to 10, where would you rank your hope at the moment?

I think it depends on what it is you’re hoping for. I mean, if you’re hoping for things to go back the way they were, I don’t think that’s going to happen, because time’s running out on the environmental clock. In terms of the environment, I think the pooch has already been screwed, and we’re going to have to change how we live entirely in order to live with the catastrophe that’s coming down the pike. But do we still have time to mitigate it? I would hope that the earth could start to survive whatever we’ve done to her, that the life force is so strong that it could start to regenerate. I mean, you look at the pollution clouds over Wuhan after they shut everything down — it’s very telling, the way the sky clears up and the air clears up.

So, I do think the earth could surprise us. But I don’t know what’s going to happen to human beings. What I do hope for — and maybe I’m at a five or a six right now on the “hope scale” — is that we will be decent through the worst of times; that we’ll be kind to each other, help each other, and share. Because everything’s going to be about cutting back and living with less: that’s what’s coming, either tomorrow or 10 years from now. But one thing that I think we have seen so far with the pandemic is, if the president and his minions could just get out of the fucking way, then people do know what to do. They know how to be kind. So, without someone fanning the flame of divisiveness and cruelty, perhaps we could fall in that direction. And that’s why I’m hopeful with Biden, because he’s not a polarizing person. If we could at least just get back to a neutral gear, then maybe our desires for decency and goodness will prevail. And that’s why my call for unity is so important. Because if we don’t win this next thing … then I don’t know how we ever get it back. I really don’t. It’s so critical, it’s sick. And they’re going to gerrymander and they’re going to hack and they’re going to do everything they can to keep people from voting, so we have to show up in the most undeniable numbers.

On a completely different note … It’s clear you’ve had a lot more on your mind than looking back on your own career, but 2020 — both the year and the album — marks 20 years since Hard Times in Babylon. Does that blow your mind at all? I don’t mean as in, “wow, time flies,” but rather, could you ever have imagined back then that that record would be the beginning of such a strong and long second or even third wind for you?

I almost think that it was my first wind when Hard Times came out. [Laughs] It was sort of like, “Now we’ve got something going!” Because up until then, I was just like, “Who am I?” But I think it is interesting that Hard Times was really about fluffing the skin off of this sort of wounded person. It was about going to the bottom of the well, like in that song “Persephone”: “On the floor of the cavern / you sort through the seas / separate expectation from the things you need.” It was about going into the cave and coming out the other side a warrior. And that’s what happened I think with that record for me; it was about mourning a break up and the loss of love, and then reaching a point within myself where I was never going to let that happen to me again. The song “Flatline” was all about that — just girding yourself to go back out there and do it right. And then from then on out, it was all about just rebuilding myself. And it’s a short step from pulling yourself out of your own mire to then starting to care about what’s going on in the world, because you’re not the main focus anymore. Once you’ve lost your sense of navel gazing and self absorption and being a victim, you start to look around and go, “Oh my god, what’s going on and what can I do to help?” And I think that would be the progression of my records in the last 20 years.

I can’t imagine a better song to have kicked off that last 20 years than “The Beauty Way,” the first track on Hard Times. I assume by now you’ve heard — or at least know about — the cover of that song that Nobody’s Girl (the trio of Austin songwriters BettySoo, Rebecca Loebe, and Grace Pettis) recorded for their full-length debut that’s coming out later this summer?

Yeah! Oh, I was so touched!

I know this isn’t the first time one of your songs — or even that song — has been covered. But I imagine this one probably feels particularly special to you. BettySoo sang harmony on both 2020 and your last album, and I assume you know Rebecca and Grace, too.

Yeah. BettySoo and Rebecca are both in our WEWIM [“Women Elevating Women in Music”] group here in Austin, so the fact that they’re doing my song with Nobody’s Girl is a real testament to our love and respect for each other.

Charlie Faye and I started WEWIM about a year ago; that was our baby. What happened was, over the years, as I got older, I was starting to see all of these other women coming up, these new songwriters, and for a while I was actually very threatened by them. And I was jealous. But there was a point I finally reached like seven or eight years ago where I was like, what the hell am I doing? These are my sisters coming up, and they’re good. They’re really good. But it’s really hard for them; the climate is even more difficult for them now than it was for me, and it was terrible for me when I was coming up. Women never got record deals, because it was all a man’s world. But there’s just so many artists out there now that it’s hard for women coming up today to even get a foothold. So I thought, I’m just going to befriend these people and see what I can do to help them. And that’s how WEWIM was born. WEWIM was initially going to be about, “Hey, let’s get together and talk strategy and about our careers,” but it’s become so much more than that. It’s a therapy group and a safe place for us to cry and to really deal with the stresses and the misogyny and all the other things we deal with, and also celebrate the wonderful progress that we are all making. It’s become a very, very strengthening and loving and supportive tool. We ended up having to close the group after we got around 25 members, just so we could keep it where everyone could be heard in our meetings, but we highly urge other female artists to do the same in Austin and everywhere. It’s the new model for how women go through this musical industry ride together. In my day, we were competitive and out to get each other and get ahead of each other — but today it’s all about, how can we help each other?

That’s really honest though, how you describe your initial wariness to that new generation: “I’ve been building this my whole life, and these kids are getting all the attention now!” Who can’t relate to that?

Yes, exactly: “I can’t buy a thrill!” And that is true, because it is a youthful industry. And there is some ageism, which I hate. But there is surrender as well when we age, and we have to be grateful about it. There’s surrender involved as these new people come in with a fresh energy and new music that’s exciting.

But you’ve never surrendered in terms of writing and producing relevant new music of your own. And although I’m not as familiar with all of your super early stuff as I am with everything from Hard Times and on, to my ears it doesn’t sound like your voice has changed that much at all. Do you think it has?

Well, my voice is a lot lower; I can’t even sing a lot of those earlier songs in the key that I wrote them in. So my voice is really going through some old lady stuff, but I have learned to adapt to it. Because there’s something else that’s emerging that in some ways makes me feel like I’m singing better than I ever sang before. I know how I want to sing these songs, and sometimes my voice won’t let me; I have to warm up, it takes me 30 minutes of warming up to sing anything. Aging is daunting, and there is a challenge there for us to do it with some grace, and to accept that we’re not at the prime of our performance abilities. But yet we have something to offer, because there’s a depth of wisdom and experience in aging that money can’t buy. So it’s a trade out, and it’s all part of preparing ourselves to leave this mortal coil, you know? You don’t get to be young forever, and we’re going to die someday, so it’s good to kind of take notes and prepare. But, the songs still seem to be coming, so that’s always a good thing. Like, thank you!

On that note of … optimistic fatalism: How’s quarantine been treating you? I got a kick out of the selfie you posted to social media with the cheese puff stuck to your face.

[Laughs] Well, I finished the cheese puffs, so that’s over! I’m actually doing okay with things in the self-discipline department, but let’s talk a month from now! It’s easy to fall into sort of a slothful place, so I try to get dressed ever day, and I try to exercise every day. We take the dog on a million walks and work outside in our garden a lot. I unknowingly planted a vegetable garden, so we’ve been eating out of that, which has been really nice. But I’m also doing a lot of stuff online. I kind of alternate between political news and family news and humor, because I think we need to keep laughing.

Are you binge watching anything in particular?

Ozark! Have you watched that? Oh my god! It’s worth going through the whole thing. The acting is so amazing and the characters are all so fully developed, and the plot lines … there’s just really nothing that compares to that. We streamed all the other usuals that people like, too, but nothing has struck us like Ozark. We just finished the third season and now we’re like, “How can we wait till the next one?”

You’re also about to start doing weekly (Fridays) live streams on Facebook, right? [Her first, from 2020‘s April 10 release day, is archived here.]

Oh yeah, and that’s been a whole project, too. Cisco helped me set all of that up in my garage.

I know you’d obviously rather be playing these new songs outside of your home, but can you see yourself getting used to live streaming as part of the new “normal,” at least as long as you have to?

Well, we set up our stage area with lights, so the lights are coming on me and I’m not just looking into my garage at my husband hanging out sitting at the computer, which would be weird. So having the lights has been helpful in that I can get into my stage persona. And I’m okay with not having the clapping at the end of songs, because I know people are out there watching. The part that I miss is, I usually like to travel with a side guy; it’s fun for me to play off of somebody. So having to play everything myself is an adjustment, and I’m used to having more toys and stuff to get just the right guitar sound and set up my voice a certain way. But Cisco has really helped by putting me through a little mixer which makes it sound a little better, so that’s only a small complaint. And, of course, I also miss selling actual product and making a living. That would be novel! I mean, I’m one of the lucky ones who can float for awhile … but I can’t float forever.

Well, here’s hoping that we can all get back out there, sooner or later. And that 2020 can still take a turn for the better.

Yes! Sooner than later. In every sense of the word.

[…] (From LoneStarMusicMagazine.com, May 1, 2020) […]