By Rob Patterson

September 2005

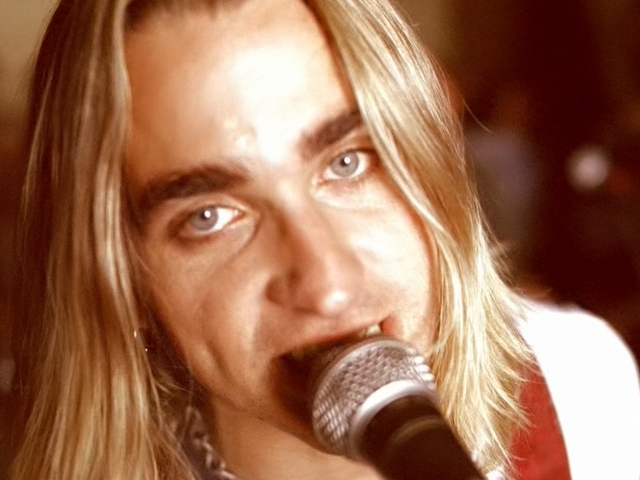

Okay, this is LoneStarMusic.com and Cross Canadian Ragweed is from Oklahoma. But we all know that Texans and Okies are soul brothers. As CCR’s singer, guitarist and primary songwriter Cody Canada notes, “Oklahoma is the biggest county in Texas.” And CCR are one of the biggest bands on the Texas music scene. Joining up together when they were all still in their teens in the tiny Oklahoma town of Yukon, they’ve built a career from knowing how to rock the house, country boy style. Five independent albums and hundreds of packed gigs stoked a buzz that rippled all the way up to Nashville and caught the ears of music business legends Tim DuBois and Tony Brown, who signed up CCR as one of the first bands on their new Universal South label.

CCR’s first self-titled major-label album proved that these feisty (if also friendly) OklaTexans weren’t about to go Music Row. And their latest, Garage, reiterates that point with a killer one-two set of punches of real Texhoma rock ’n’ roll. As the title implies, this 14 song set is all about rocking out just like they did when the band first started, albeit with a good decade of experience under their collective belts. In addition to songs written by Canada and the band, there are collaborations with Mike McClure (who is also CCR’s producer), Stoney LaRue, Wade Bowen and Randy Rogers as well as tunes by Todd Snider, Texas singer-songwriter Scott Copeland and the legendary Bo Diddley. It’s an album that screams “turn it up!” from the moment it hits the player yet also gives the listener cool food for thought in the lyrics. In short, it rocks.

We caught up with Canada — who now lives in the New Braunfels area, making him now a Texan — just a few days before the birth of his first son: Dierks Cobain Canada. (Look for an Q&A later this month with drummer Randy Ragsdale, guitarist Grady Cross and bassist Jeremy Plato.) It was obvious that Cody and his wife (and the band’s manager) Shannon didn’t know the gender of their child when asked if they knew what it would be. “Nope,” he answered, then quickly added, “A Texan!” Hell, yeah!

Taking a cue from the title Garage, it seems to me that this album has an implicit theme all about being being in a rock ’n’ roll band and what rock ’n’ roll means to you guys. Is that a fair guess?

Yeah. That’s the theme you’re getting from the record?

I sure am.

It seems like every record we make there’s always a theme but it’s never really on purpose. It just kind of happens. It seems to be working for us. We went into the studio with five songs, and we ixnayed one because our producer Mike McClure didn’t think it fit the album. At the time we didn’t really have an album. All we had was four songs. So we just wrote ’em as we went and dug up old ones and finished some songs that were on blocks. To me it’s our most creative thing because we had time. I guess the only goal to this record was to get it done. We had time, but then again we didn’t. I told the record label never to put us on a time schedule and of course they did. I guess the theme of the record was to just try to make a good record.

How do you feel it fits into your catalog?

Soul Gravy to me was my favorite — but I say that with every record — just because it was the first mature record that we ever had. But this one got me in the end. When I sat back and threw it in my truck and listened to it, it was like, all right, now we’ve got something.

The initials of your name, CCR, are the same as that of Creedence Clearwater Revival. Your sound is different, but do you feel there’s a spiritual parallel with that band who also rocked out country style?

Yeah, I see it. Yeah, we’ve been fighting that for like 10 years. I think we maybe did one Creedence song, “Suzie Q,” a long time ago back when we were playing 25-person capacity bars just because if we didn’t play it we’d get our ass kicked. But I do think there is a parallel similarity there because they did something different and I think we do something different.

You are probably the most rocking band at a Nashville record label as well as within the Texas/Red Dirt Music movement.

We’re definitely more rock than anything. My dad would rather hear steel guitar and fiddles. We grew up listening to Haggard and Willie, so we always say that we’re a country influenced rock band. But it’s definitely more rocking than most, which is why we have a hard time getting on the radio, which bothers us about five percent of the time. The rest of the time we don’t really care. As long as we’re making a living and feeding our families and out there supporting our habits — because I guarantee you that off the road for a week and a half we start jonesing for it — and as long as we have people that want to see us, we could care less.

You’ve done a damn good job of being on a Nashville label and not getting compromised one bit in doing so. Any advice for other acts from the Texas and Oklahoma scene on how to pull that off?

Oh man, I’m not good for advice because if it goes wrong it’s my fault. I don’t know. The thing that we always did was never changed anything. From the git go, from 10 1/2 years ago people saying we need to change our name, to now people saying, well, you need to do this if you want this person to do a favor for you. It’s like, no. Just do your own thing. My big thing is always be honest. I heard Guy Clark say one time in an interview I read: If there’s not a true story, then make people believe it. I’ve always stood by that one. I try to write about everything that’s going on around me or happening to me or my friends. I try not to write too many tunes that are made up. I think you’ve just got to be honest. If you really believe in something, don’t be an ass, but believe in what you do, believe in your heart. I know that sounds cheap, but …

I’ll tell you what: I read a Robert Earl article that said don’t be too stubborn because it could bite you in the ass. Everybody’s still learning, you know? I learned from that, and I read that just a couple of weeks ago. And I said, oh wow, I never really thought about it that way. Stand up for your own guys, but don’t be too stubborn or you’re going to be backtracking.

There’s a common sentiment down this way of “Fuck Nashville.” Is it safe to say that you don’t share that feeling?

I’m not going to mention any names, but we’ve seen people preach that for 10 years and then succumb to that. We’ve been guilty of saying things before, but we’ve got a lot of friends in Nashville. About 75 percent of the music coming out of there I can’t stand, but that doesn’t mean that the person doing it is a bad person. There’s about two percent of them where I don’t care if they’re Santa Claus, I don’t want to meet them because their music is so bad. But it’s not really the artists up there, it’s the machine. I remember when the Great Divide signed with Atlantic, I told this fellow Okie that’s on the scene that used to play with Garth Brooks, “Man, I think something’s really fixing to happen.” He said, “I’ve been hearing that for 20 years.” And that was about nine years ago. Then once we got to poking around and getting to know people in Nashville, I saw that they know what’s going on and they look at this stuff in Texas and Oklahoma and see the big crowds and stuff, but they’re too afraid to change. I mean, God forbid you go back to singing about Merle Haggard and speaking the truth. Nobody wants to hear about you being drunk and losing everything. They want to know how snappy you dance. Horseshit! Some of that music — the majority of it, I guess — just doesn’t have traction. I’m about to have a kid, but if I write a song about sippy cups and being Mr. Mom, shoot me.

I always say on stage that there’s four people that still keep it alive for me: George Strait, Gary Allan, Dierks Bentley and Lee Ann Womack. To me, they’re country, Even Gary Allan’s Vertical Horizon song [“Best I Ever Had”]. For the spot that that guy’s at in his life, that song is perfect. And it’s country. It’s sad, and if you want to pigeonhole country, its sadness and losing things.

The thing is with Nashville, you go out there on a Monday night and you go to three or four bars, and you find the right ones, you’re going to hear some really good music. They’ve got some music. “Fuck Nashville” is a big one amongst all of us. But the more we got into it, the more I realized, you know, it’s more the industry. I’m not saying this about our record label, but there’s a lot of labels up there that have been doing so much for so long that, I think — and they’ll probably grill me for this but I don’t care — they just don’t know what’s going on out here on the battlefield.

You have to be the only act on a Nashville label that has a song [“Dimebag”] that pays tribute to the late Dimebag Darrell.

But I am sure it’ll get swept under the table. Not with the fans it won’t, but with the industry. And who gives a shit? We all want to do something in life. But as far as I’m concerned we can play the same clubs we’ve been playing for the next 20 years and still have as much fun as we’re having.

Is it safe to say that you care more about making music you are happy with than having a big country radio hit?

That’s one thing I say almost every night. You know, we had one song that went to No. 33. And that was good, it was cool. It didn’t really rattle our cage any. But all these guys that are No. 1 might be around for a while. But you’re gonna have to shake the tree to get us to leave because we’re going to be here for a long time.

Is the fact that you all grew up together in a small town what makes the group so solid and determined to go the long haul?

That’s it, you said it. We’ve known each other forever, for 20 years, some of us longer. That what did it for us. I see my sister 10 times a year, and that’s not nearly enough. But I see these guys almost every day. And if I go a couple of days without ’em, I have to call ’em — “hey, what are you doin’?” We’re closer than brothers most of the time. I’ve seen brothers fight more than we do. And if somebody gets their panties twisted over something, we sit ’em down and say, “hey, what’s wrong?” “Well, this is bothering me.” “Well, let’s fix it and get over it and go rock ’n’ roll, because it ain’t that bad.”

Did you see music as the one way out of Yukon?

I’m not a real fan of my upbringing in the town that I grew up in. I had a hard time growing up with the educational system. I got kicked out of school when I was a senior because I was living on my own, and my folks had split up — long, drawn-out story. I was feeding myself. And I got kicked out of school because of low attendance. And I went directly to music, and I’ve been there ever since. I think if we’d grown up around music 100 percent, it would have been a little different. We were the only thing going on in Yukon. And we were the only guys in a band that took it seriously. Some of the parents were gung-ho, and some of them were, “Get a job.” And you know what? You can’t do anything about it. Hold college over our heads. Who gives a shit? We’re going to do what we want to do.

How do you feel about the fact that to some people you aren’t country enough and to others you are too rock ’n’ roll?

You can’t be too rock ’n’ roll. And talking about rock ’n’ roll, to me — and this is my opinion — the only thing I like in rock ’n’ roll is the guys who have been doing it for a while, like Audioslave and Velvet Revolver. To me, that’s still rock ’n’ roll. Not crying because your dad hates you. It’s straightforward rock ’n’ roll — turn it up and listen. Like Foo Fighters. Dave Grohl has been doing it forever. And that’s the way it should be.

I’m tired of doing the interviews where they go, “well, you guys aren’t that country.” Well, no shit! We never claimed to be a country band.

But you are a band from the country.

Country boys playing rock ’n’ roll.

No Comment