By D.C. Bloom

(LSM Jan/Feb 2012/vol. 5 – Issue 1)

A guitar is much more than just the tool of a musician’s trade. A guitar can be a decades-long dear friend, one that has been there close to the heart through thin and thick, a constant companion in the lean times when no one could have imagined that the person strumming it would ever find a loyal audience, let alone a career or even fame.

It can be a beloved heirloom, handed down from one generation to the next and cherished, not so much for its sound and feel, but for its genealogical sentiment and family ties.

Guitars are certainly not just wood and steel. A cherished guitar can seemingly be a gift from the musical gods, a mystical instrument that magically finds its way into a performer’s hands. Or maybe just through serendipity.

It can be a battle-worn veteran of the road, bearing the scars of a lifetime of service — like Willie’s legendary Trigger — and the signatures of both the famous and obscure who may have meant something special to its owner.

A guitar can be a lost love, stolen away in deep December, never to be seen again, but always longed for and remembered as the one that slipped away.

Guitars and their stories can be as powerful, inspiring, mesmerizing, or haunting as the ballads played upon them.

These are the stories of some of the favorite instruments played by some of your favorite musicians.

***

Joe Ely’s cool — and cheap — rockin’ Loretta

Hard times and troubles

been doggin’ our tale.

If you’ve got the dough,

Buddy, take her and go,

this guitar is for sale.

— Shel Silverstein, This Guitar is For Sale

“I’d been playing at the old Cellar Club in Houston, and the electric guitar I’d been using there was stolen. After a falling out with the guy who ran the place, a friend and I decided to head out to California. This was 1967, just before the Summer of Love. The only possession I took with me out there was a Super Reverb amp, and the first couple of nights I slept on Venice Beach with that amp as a pillow.

“One day I happened to see a guy at a bus stop playing an old Gibson guitar. It was a down-and-outer, pretty beat-up looking and kind of just wired together. The bridge was a pocket comb and he’d glued seashells all over it. It was a pretty homely sight. But it was a Gibson, after all, and the body looked to be in decent shape. He told me he’d been wanting to sell it, and I could tell he was on speed or something, because he was really jacked up. I told him I didn’t have any money on me, but if I could come back the next day with the 10 dollars he said he wanted for it, the guitar could be mine. When he said he just wanted 10 bucks for it, I just gulped. I mean, this is a Gibson, and I knew that the thing could be fixed up. So I asked ‘Where will be you be tomorrow?’ and he said, ‘Oh, I’m always right here at this bus stop.’

“Well, I went and borrowed a little from the only person I knew in California — the friend I’d gone out there with — and sold Coke bottles I’d found on the beach and did everything I could in that 24-hour period to come up with the 10 bucks. But I only raked up six dollars and change and so I took that down to that bus stop the next morning. Sure enough, he was there and I offered him all I had. He looked at me rather disgustedly and said, ‘Oh, is that all you could get?’ and I said, ‘Yeah, that’s all.’ He thought about it for a couple of minutes and finally said, ‘Alright, I’ll take it, but I get to keep the seashells!’ And then he up and ripped the shells that’d been glued on with model airplane glue or something and I was afraid the whole top would come off.

“When I came back to Texas, I took it to a guitar maker in Lubbock and he put all new frets, a new fretboard and a new bridge on it. It was already 20 years old when I bought it and it’d been played hard. The frets were completely worn into the wood, so it’d been hammered pretty good. That guitar has hitchhiked from coast to coast with me and I’ve jumped freight trains with it from Lubbock to New York City. It’s what I played with the Flatlanders and it’s been in just about every state and all over Europe. And I still use it. It’s the guitar I’ve used to record acoustic on every record I’ve ever made. So it’s served me well. And to think it was a really close call if he would take what little money I had to give for it.

“In those early years, I called it Loretta, but she’s kind of outgrew that name. Loretta kind of became a song, so now I just affectionately play it and don’t call it by name.”

Sara Hickman — You never forget your first

“I get teary when I think of my first guitar. I was about 6 and taking piano lessons and I told my mom I wanted to quit. She agreed, but said I had to play some kind of instrument, so we went to the music store and I pointed at this one guitar and just loved it, loved it, loved it. I’d rush home from school each day and played it all the time. It was a little Yamaha guitar with steel strings and had a little silver heart on it. But I was a little entrepreneurial kid and I was always setting up stands to make money. I’d sell my Halloween candy if I had my eyes on something special. So I’d decided I wanted a new guitar and I sold that first one for 10 dollars to a neighbor kid. Forty years later, I’m doing an interview and I’m asked if I have any regrets. I said, ‘Yeah, I guess I have one big regret. I sold my first guitar for 10 dollars and I wish I could have that guitar back, because I’m really sad I sold it.’

“Well, about a year later, my youngest daughter comes running into the house and says, ‘Mom, there’s a guitar on the porch.’ I went out there and saw a vacuum cleaner box, so I say, ‘Well, you’re obviously mistaken because someone has obviously sent us a vacuum cleaner.’ But we took the package inside and before I could get the bubble paper off, I just knew I was holding my first guitar. It’d been sent UPS from Houston so I called them and they said that the person who sent it wanted to remain anonymous, but they hoped I had enjoyed getting it back … It’s almost like you hear these stories of pets traveling 500 miles to get back to their owners and you think ‘how does that happen?’ It really is a miracle and it was pretty cool that my daughter seemed to sense that it was a guitar in that box. I’m just very grateful my guitar came back.”

Cody Canada — Going for the silver

“I played Fenders from 1994 to ’98 — Telecasters and Strats — and they did it for me and sounded great, but I was looking for a silver guitar. I saw a Fender Honolulu special edition that was really cool looking, but it had a $10,000 price tag on it. I’d only been married a year at the time and I told my wife I really wanted it, but I also realized we couldn’t afford it. Besides, I’d gotten the chance to play one and when I plugged it in, it just didn’t sound that good.

“So, Christmas 1999 rolled around and we were at her mom’s house and there was this giant present under the tree with my name on it. I unwrapped it … and it was a wakeboard. I tried to be cool and said, ‘Oh, wow, thanks.’ But we didn’t live by a lake, ya know. This was Central Oklahoma. So I just figured maybe she was planning on us going wakeboarding somewhere next summer. I slid it to the side and she goes, ‘Open it up, Cody.’ So I finally opened the box and see it’s a guitar case. And inside was a Paul Reed Smith guitar — silver. I mean, I had only dreamed of Paul Reed Smith guitars. I had never played one, but I knew that they were top-of-the-line. I picked it up and played on it with no electricity and just couldn’t wait for New Year’s Eve to jam it. We came down to New Braunfels for that New Year’s Eve show and I plugged it in and I have never been the same.

“When I got it, it was brand new – not a scratch on it. Now it’s beat to hell. It looks like it’s about 30 years old. I’ve played 260 dates a year for the last 12 years of my life and that guitar’s been there the whole time. It just gets better with age. Now I’ve got a Paul Reed Smith sponsorship, and when he made the offer I told him, ‘I could buy guitars off of you or you could give ’em to me, I appreciate it, but you’re never gonna duplicate this one.’ He’d been asking me to ship it up so he could work on it, but I told him, ‘Me and this guitar are married and I know nothing’s wrong with it and I don’t want ya messin’ with it. I know you’re the creator, but I just don’t want you to jack with it.’ But I went up to the plant a couple years ago and looked over this back as he worked on it. He sanded the neck down and made it smoother. Fixed a few things up where they weren’t broken, but they weren’t perfect. And then about three years later I went back and he wanted to repaint it. And I said, ‘No, man, you can’t repaint it. If you paint it and redo it, then I’m screwed.’ It’d be like Custer cutting his hair off. So he said, ‘At least let me clean it. There’s some black stuff in between the cracks,’ and I told him ‘I’m pretty sure it’s Jagermeister and cigarettes.’ So he told me to leave the room. Said he wasn’t gonna do anything to it or modify it, he was just gonna clean it, but he said, ‘I really don’t want you here cuz I’m gonna take it completely apart.’ So he took it apart right down to the last screw. And once I got it back, it played like it was brand new again.

“It’s been everywhere with me, from France to Germany, Italy to everywhere. The only scratch on that thing that I ever put on it on purpose is where I took a knife and etched ‘#1’ on the back. That’s my number one guitar and it always will be. Seth James and I went to the plant about six months ago and there’s all these brand new, beautiful guitars, and then there’s mine that looks like it’s been dragged behind a truck, and his quote was, ‘You officially have the sluttiest PRS in this factory.’”

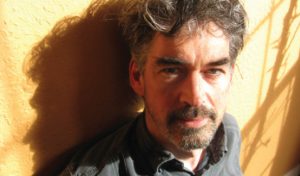

Slaid Cleaves — Grad-school Gibson

In 1965, Slaid Cleaves’ father was a graduate student in Washington, D.C., juggling the academic demands of seminars and dissertations with domestic duties such as diaper changing and managing the young family’s modest finances. But when a musical fellow feels the need to upgrade his guitar, well, chances will be taken and marital bliss be damned. So the senior Cleaves did what any guy with a 1-year-old future Kerrville New Folk winner at home would do: He got rid of the cheap Kay model guitar he’d been strumming and purchased a brand new Gibson J-50. “He had to keep that guitar hidden in the trunk of his car and for about a year could only drive down to the park to play it, because he bought it without mom knowing,” Slaid says with a laugh. “It cost him $145, which was probably an entire month’s rent for them at the time.”

But after a year or so in exile, the Gibson became an accepted part of the family, and Cleaves fondly remembers his father breaking it out at parties to play “My Bucket’s Got a Hole in It” and “Puff the Magic Dragon.” Cleaves inherited the J-50 in the ’70s, when his father upgraded again, this time to a Martin and with spousal approval. The grad-school Gibson has been his main guitar ever since. “I’ve thought about replacing it, but it’s sentimental,” says Cleaves. “And I just think that old guitar’s deep dull Gibson rumble complements my voice pretty well.”

Dustin Welch — Carson, the catalog guitar

“I was probably 8 or so when my dad got me my first guitar. It’s a Carson J. Robison guitar from the mid-30s. It’s a Montgomery Wards catalog guitar that we suspect was made by Gibson. It’s hard to tell because with those catalog guitars they’d shop it out to a lot of different guitar makers. It looks like one of those old Kalamazoos. I had been starting to pick up Dad’s guitars around the house and fooling around and he said, ‘You want a guitar?’ So he bought it from a neighbor, Kent Blazy, who had just had one of his songs, ‘If Tomorrow Never Comes,’ recorded by Garth Brooks. I think dad paid about $250 for it. It’s got a big fat neck on it and is old as hell. It was fairly beat up already when I got it, and probably not your typical first instrument or something you’d get if you were first learning. And I’ve beat it up pretty good, too, I think. When I was 10, I carved an Indian design in its body. There’s an Indian tribe on my mother’s side of the family and a cool design they’d tattoo on their hand. I knew I wouldn’t be able to get my hand tattooed for many years, so I decided to carve it into the guitar. Again, probably not the kind of thing you should do to a 70-year-old guitar. But I never intend to sell it. I’ve always used it for performing and actually tried to retire it a couple of years ago when Dad attempted to give me the Gibson that he’d been playing for 20 years. I tried to work with that one for a couple of months, but it didn’t last. It’s just the feel of that old guitar more than anything. My hand sort of grew around the neck of that guitar, literally. It’s pretty finicky. The tuners squeak and there’s hardly any bridge left. But I put up with it. It’s kind of a crotchety old man, really.”

Ray Benson — A Texas tall tale

“I’d been playing a 355 and I’d been playing a Telly, but I wanted something in between the two. So I asked my guitar company to make me a Telly-like guitar that was bigger than a Telly. I mean, I’m 6-foot-7 and the Telecaster looked like a mandolin when I played it. They made me one with a larger body and put a Texas-shaped pick guard on it. Then I went to a NAMM (North American Music Merchants) show and a guy from Valley Arts Guitars was there at the time and he’d had a guitar body and neck that he’d hung on the wall as a decorative piece. It was beautiful, just a gorgeous piece of wood with no pickups on it or anything. Just hanging on the wall as something to look at and draw people into his booth. I said, ‘Put some pickups on that thing and let me see what it’s like.’ They made a real nice neck for it, too, and I’ve been playing it ever since. It’s been my main stage guitar now for 20 years or so. And it just started out as a wall hanging. It’s sort of a guitar that was never supposed to be. The funny thing about the Texas-shaped pick guard is when I play it the state of Texas is on its side. Dave Sanger, the drummer for Asleep at the Wheel, gets more comments for his Texas-shaped cymbal. But I’m having another one built that’ll have Texas facing the right way for the audience.”

Junior Brown — Guit-Steel to where you once belonged

“Junior Brown was playing with Asleep at the Wheel when he thought up that guit-steel guitar, and it was born out of necessity,” recalls Ray Benson with a laugh, “because he was so slow changing between guitar and steel guitar.”

Whether actual fact or a bit of musical history embellished over the years, Junior Brown has been hitting the stage with his brainchild instrument for a quarter of a century now and the two continue to dazzle audiences with a sound and style that is a whole lot cooler than the sum of its parts. He called that first guit-steel “Ol’ Yellar” — after the color of its finish. “I knew when I first played it that it was a keeper,” says Brown. “I once heard a story about Lindberg when he build The Spirit of St. Louis. They all expected him to taxi around and try it out and get the feel of it before he took off for the first time. Well, he didn’t taxi a bit, he just took right off — with confidence. And that was the way I was when I went onstage for the first time with the guit-steel at the Station Inn in Nashville along with an all-star lineup that included Peter Rowan. I just played it like I’d been playing it for years.”

Brown has trademarked the name “Guit-Steel” and along with guitar maker Michael Stevens, who helped him bring his design to life, they’ve made three more since Ol’ Yellar started to howl. A fourth was made by Peterson Precision Instruments, which Bob Dylan asked to buy “but I just gave it to him as a gift,” says Brown.

Brown’s guit-steel is a common sight these days and it’s not seen as the novelty instrument it was in its early days. “I was with a friend of mine and a fan walked up and says ‘Wow, I haven’t seen one of those in long time.’ My buddy leaned over and said to me, ‘Yeah, like never.’ Because while it’s something that looks like it came out of the ’50s, it’s really not an antique.”

Ray Wylie Hubbard — In the neck of time

Traveling to a folk festival in Little Rock in the mid-90s, Ray Wylie Hubbard stopped in a sleepy Arkansas town for a fill-up, sauntered into the service station and started chatting up the gentleman behind the counter. An unusual sight over in the corner caught Hubbard’s eye — an old guitar neck buried in a flowerpot with ivy twirling up the fretboard. He was told the neck had been in that position since the Nixon Administration, when the White River Flood of 1972 had claimed the guitar as a victim.

“I could see it was a good guitar neck,” says Hubbard, so he asked if the gentleman would be willing to part with. And why wouldn’t he? A simple stick could prop up those vines just as well, and the guy was pretty sure he had the rest of the guitar just taking up space in a shed somewhere. “About two weeks later, a package arrives with the neck, sides and the back,” says Hubbard. “I took it to Tony Nobles in Wimberley and he made a new top for it and put it all together.”

Hubbard’s Arkansas find turned out to be a 1929 Regal Resonator. The round silver cone was missing, however, and in its place was a wooden plate that he suspects was put on the guitar during World War II when the silver would have been of value to the war effort. On the back of the neck, Hubbard noticed that there were deep ridges cut into it behind where the 5th, 7th and 9th frets were, and the guitar detective in him figures that it belonged to a blind guitar player who depended on the cuts to navigate the fretboard. Back in action after two decades of upright service to a potted plant, the Regal Resonator is now occupying a place of honor in the Snake Farmer’s collection.

Walt Wilkins — The South Austin Saxon swipe

“I needed an acoustic that wouldn’t feedback for a festival I was about to play, and Don Pitts at Gibson in Austin had told me if I ever needed a certain guitar to come in and borrow one. At the time they had a new model called the Americana that I’d used before doing a show with Pat Green and really liked. He said I could use one of their new ones, but then said, ‘Hey, let me show you something cooler.’ So he brought out this one-of-kind Americana model guitar that had been made out of wood from an Army/Air Force barracks in Marfa that they’d torn down and Gibson had made three guitars from it for some benefit that ended up never happening. So anyway, they had these three pretty unique guitars. One, they gave to Willie Nelson. Another went to Dan Rather. And Don gave the third one to me. It had actual rivet holes in it and I loved that guitar. But it was stolen on Dec. 23, 2009 from the Saxon Pub. That was a guitar I never left in the van, ever. I would even take it into restaurants with me. I left it alone, though, for one minute too long when I went to get paid. And somebody grabbed it. I looked all over South Austin, in every dumpster and everything. It was windy and cold and I got home about 4 in the morning and put something on Facebook. Three hours later there were hundreds of responses from friends and fans saying they’d help find it. The police were looking for it, too, and we searched every pawnshop in Austin. The outpouring of support was tremendous. But we’ve never had a lead. Not yet. Man, I really miss it.”

Bill Rice & Rich O’Toole — Call it kindness, not luck

Like many a Texas musician before and since, Bill Rice was down to his last few dollars in the late-90s and the only move he had left was to pawn his guitar. But it wasn’t just any guitar; it was a 1967 Gibson Hummingbird that his grandfather had bought brand new. In fact, Rice had the original receipt. He figured it was gone for good after the pawnshop played hardball and wouldn’t let him buy it back when he showed up a few days after the allotted time had expired.

Rice didn’t have the heart to tell his father about the lost Hummingbird. “I lied to him for years and must have looked in every pawnshop in Austin and San Antonio,” he says, but it was nowhere to be found. The hurt was so bad that after he’d gotten an endorsement deal with Gibson, he couldn’t even bring himself to play an offered-up Hummingbird.

After sharing the story of his long-lost, sweet sounding guitar, he was told that a fellow musician – Rich O’Toole, with whom he’d be doing a show in the coming days – had a pretty nice ’60s Hummingbird of his own that his parents had bought as a graduation gift. When O’Toole opened the case to show off his guitar, “I knew immediately that was my guitar,” Rice recalls. He knew the serial number like he’d known his own birthday and turned it over to see the crack it had sustained at the foot of a drunken cousin who had once stepped on it. “I was balling like a baby. I couldn’t contain myself.”

And O’Toole, a true country gentleman, told his friend it was his and that he should take it back home with him that very night. The Hummingbird really hadn’t flown that far after all; the O’Tooles had bought it at a vintage guitar store less than two blocks from where Rice had pawned it.

Dale Watson — Down under and over Euro

“Back in 1997, I met Allan Tompkins from Australia at the NAAM show in Nashville. I tried out some of his guitars and loved them and remembered them. A while later, I was playing the Golden Guitar Festival in Tamworth, Australia, and Allan had a booth there as well. They were doing a showcase with the Emmanuel Brothers and I just gravitated towards that booth. I picked up the guitar I play now. It was so light. A lot lighter than it is now with all those coins on it. He’d shaved the top off and routed out each side of it, then put the top back on. It’s made out of Australian Oak, the neck is Australian Silky Oak and it has Bill Lawrence pickups. It’s got a phase shifter built into it and a Sabine tuner attached to it. It’s been the hammer since ’97. It’s just like an old shoe, ya know? And I’ve not put new frets on it, either. It’s just one of them things. It’s a workhorse. It’s not like I don’t play a lot; I play a whole lot. I don’t have a heavy touch but I’ve played four-to-five nights a week ever since ’97. When I’m on the road I play every night.

“In 2000, I was ending up a long, long tour of three continents, but I realized that when I left Europe I had all these coins that would be worthless by the time we’d be back because the Euro would be in use. I had about four pounds of coins and I was looking at the German Deutsch mark and the Italian lira and I thought I’d just put ’em on the guitar to remind me where I’ve been. Some have fallen off over the years and some people stole others, but other folks started giving me replacements. The Dutch golden guilder got popped off by airport security. The Secret Service have given me things to glue on it — little mementoes. I’m drinkin’ most of the time I glue ’em on, and there’s no rhyme or reason when you’re drinkin’. I did an acoustic tour of Europe where I took the guitar Allan had made me with the Texas soundhole, but I got all kinds of hell from people for not bringing that electric guitar with the coins. It’s crazy, but that guitar’s got its own fan club. But it’s definitely locked me in.”

Terri Hendrix — Small instruments, big dreams

The Tacoma Papoose that Terri Hendrix plays has become a magnet for the children who attend her always family-friendly shows. They’re drawn to it not only because of its diminutive size and the cool banjo/dobro sound it makes, but because it’s been Sharpeed, signed and sketched upon by kids from across the country. “It started in Arkansas with a little girl who had recently learned to write her name and she wrote ‘Christina’ in big letters with a backwards ‘C,’” Hendrix recalls. “She had other friends or relatives with her and so I had to let them sign it, too.”

Such are the manners and what-the-heck nature of one of the hardest-working and nicest performers in the Texas music business, because it’s not like the small but mighty instrument didn’t already have a firm hold on her heart. “I had the Papoose for a week and wrote ‘Clicker’ on it,” Hendrix says. “That song just landed in my lap.” But the bond between player and instrument has grown right along with its piped-piper-like pull on kids because of the things they write. The sentiments they share leave Hendrix laughing and humbled — hedged-bet platitudes such as “Not so bad” or “You’re kinda cool.” But one particularly simple message spoke volumes with its sincerity.

“We were doing a show for underprivileged kids in Austin — children in need of families. And one little girl chose not to write her name. She could have written or drawn anything. But in bright green ink, she chose to draw a house. It really got to me. That little instrument means a lot.”

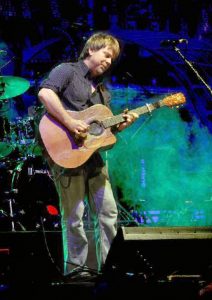

Monte Montgomery — Last guitar standing

“As soon as I saw this Alvarez at Parker Music in Houston and put my left hand around the neck I knew it was the one. So I traded an electric guitar, a boogie amp, a flight case and not a little cash to get that guitar, and at the time I knew I was being taken for a ride a little bit, but I really wanted it and I didn’t really need that other stuff. That happened in 1988 when I found it brand new. And now, all these years later, I’m still playing that same guitar.

“Over the years, many guitar makers have built guitars for me in an effort to give me something similar. I love my guitar, but it’s just kind of scary that I only have one that I’m really comfortable on. So at this point, I own a lot of beautiful guitars, but there’s only one that I play a lot. There’s just something about that guitar and the way it’s aged. It’s just irreplaceable. It had a satin finish on it, not your typical lacquered sheen, and I think that’s why it sounds like it does. You can literally take your thumbnail and push it in the guitar and it’ll leave a mark, it’s that soft. Because that’s the kind of wood it is and it’s not that well protected. It’s aged a lot quicker than another guitar would have. It didn’t always sound like it does now. The longer I’ve played it, the more mellow it’s become. It has a cutting mid-range and more lows than you’d expect. Other guitars don’t have the same kind of balanced warmth. You simply can’t have a new guitar sound like an old one. It’s not gonna happen.

“There’s just a real connection between me and that guitar. Honestly, I like the idea of seeing me with another guitar, but the only drawback to that for me is that when you pick up another guitar it kind of directs you in a different way. It’s like ‘this guitar makes me play this way, and that guitar makes me play that way.’ It’s just very cool that I’m so very familiar with it. But at the same time, I feel like sitting down with a different guitar and a lot of times when I write music I try to get away from that guitar and pick up something that’s a little bit foreign to me. Because that brings out something different in you. But I’m always gonna play that guitar whether it’s 100-percent of the time or if it’s sitting next to something else.

“I guess there’s also a certain attachment to it that fans have. They’ll give me pictures of me playing and I’ll look at them and I can’t tell when it was. I figure, ‘Okay, I’ll add these to the 1,000 other pictures I have of me playing this guitar.’ It’s kind of crazy. It’s just all beat to hell. It’s been in a lot of smokey bars and had alcohol poured over it over the years. It’s been shipped on airplanes and left in my car when it’s 110 degrees. Crazy shit like that. We’ve definitely been places together. I call it Excalibur because I love that mythology stuff and the idea that it’s a one in a million and only works right in the hands of just one person.”

Six Strings From Six Feet Under

Townes Van Zandt passed away on New Year’s Day, 1997, and in the days to follow, his son, J.T., would travel to Nashville on a mission. “Townes played cheap guitars in those early years and really didn’t care,” says J.T. today, “but in the ’90s, friends convinced him to get a nicer one. He got that Gibson J-200 around then and just loved it. That’s the one thing I was determined to bring back from Nashville after his death.”

It wasn’t the first time J.T. set his sights on a guitar whose owner had gone too soon. While Townes had famously — and most likely facetiously — claimed that he had dug up Blaze Foley’s coffin to retrieve the ticket for a pawned Foley guitar, it was J.T. who went “from pawnshop to pawnshop with Calvin Russell” to track down the Duct Tape Messiah’s gut-string classical guitar. “We finally tracked it down to a place on South First and paid $150 for it. I was young and dumb and took off a sticker Blaze had put on that said ‘Onward Through the Fog.’ In retrospect, that sure was a stupid thing to do.”

Another Foley guitar – which has more than 100 signatures of peers and admirers carved into it, including Willie Nelson and Joe Ely – took a circuitous route from Blaze to his sister, Becky Weldon, who owns it today. Foley had apparently borrowed the guitar from someone named Big Richard, but after Foley was killed, his friend Michael Barker had given it Weldon. But when the mysterious Big Richard reentered the picture and asked that it be returned, “I kindly took it back to him,” says Weldon. Years later, Weldon got a Thanksgiving night tip that the guitar was about to be pawned by an acquaintance of the by-then-deceased Big Richard and she’d best hightail it to Austin before it was. “I have it now, and it’s not going anywhere. I’ve left it in my will to my son,” she notes.

Myrtie Payne, daughter of Leon Payne, had to resort to a bit of subterfuge to get her hands on the guitar that Hank Williams had given her father after hearing him sing “Lost Highway” in a Houston bar. “Hank asked Daddy, ‘Who wrote that song?,’ and Daddy said he did. Then he heard him sing ‘They’ll Never Take Her Love from Me,’ and Hank asked if he’d written that one, too, which, of course, he had.” Knowing a great country song — and songwriter — when he heard it, Williams gave Payne a Martin guitar as an enticement to take his tunes to the legendary Acuff-Rose music publishing firm in Nashville. “When daddy passed away, I told my mother I really wanted the Hank Williams guitar. But she said she was giving it to my stepsister. So I just put the Martin in a Gibson case and walked away with it.”

***

So the next time you see those finely-tuned guitars in their stands on the stage waiting for another workmanlike performance by their owners … or hanging on the walls of the neighborhood music store ready to be claimed by a kid with a dream as big as Texas … or being carried onto a crowded plane because that touring singer-songwriter simply wouldn’t stand for their longtime companion being stowed down below with mere luggage, remember that they’re much, much more than just musical instruments. They’re stories waiting to be told. And songs waiting to be played.

No Comment