By Eric Hisaw

(LSM Oct/Nov 2010/vol. 3 – issue 6)

Waylon Jennings took on the country music establishment armed with a leather-covered Telecaster, a bag full of songs by the hippest writers around, a rare vocal gift and a Buddy Holly beat. In a 45-year career, he would endure all sorts of trends and tribulations, release more music than anyone could ever listen to and revolutionize the business. The Waylon Jennings story began on the dust-blown plains of West Texas, where he was born in Littlefield — a “suburb of a cotton patch” as he’d often describe it. Though he left Texas as a young man, never to live there again, the Lone Star State figures heavily into Waylon history. It was in Texas that he first found mass popularity, and Texas songwriters who would provide material for many of his greatest recordings.

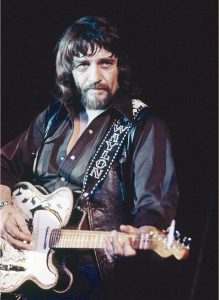

Though he was a commercial force in the ’60s, an icon and TV star in the ’80s and an elder statesman in the ’90s and into the first decade of the new century, the ’70s were really the defining decade for Waylon Jennings. In a storied battle with RCA records, Jennings had wrestled creative control from the architects of the “Nashville Sound,” stripping away the wall of strings and vocal choruses and bringing in his own funky bunch of road-tested players to create a trio of albums with the depth and quality to rival the work of the Rolling Stones or Bob Dylan. 1973’s Lonesome, On’ry and Mean kicks off with a Waylonized run through Steve Young’s drug-induced title track. The raw twang of the Telecaster and the thumping “four on the floor” of the bass drum immediately announce this is something new. With the soaring waltz of Bill Hoover’s “Freedom to Stay,” Gene Thomas’ philosophical “Lay It Down,” the definitive version of Danny Okeefe’s “Good Time Charlie’s Got the Blues,” Mickey Newbury’s grim “San Francisco Mabel Joy” and the closing guitar and pedal steel jam on Kris Kristofferson’s “Me and Bobby McGee,” Lonesome is solid throughout. Jennings’ big Texas baritone and Ralph Mooney’s pedal steel keep it country while the lyrical themes and rhythms venture into folk, rock and soul.

Later that same year, Jennings would unleash the songs of a drifting cowboy poet from Corsicana, Texas, named Billy Joe Shaver on the world at large through his next LP, Honky Tonk Heroes. Cut mostly at Tompall Glasers’ studio away from the RCA suits, union logs and clock-watching session men, Honky Tonk Heroes is the ultimate modern cowboy concept album. Shaver had turned a lifetime of hard living into material for songs. Jennings and his road band, augmented by Muscle Shoals guitarist Eddie Hinton and acoustic picker Randy Scruggs, turned those songs into an undisputable classic. Driving acoustic guitars, twanging pedal steel and that patented thumping bass frame Jennings’ stunning vocals. Legend has it Shaver was upset at times with Jennings for “messing with the melodies,” and he would go on to cut excellent versions of almost all these songs himself. The nine Shaver compositions on the album are capped off with a bold take on swamp-rocker Donny Fritt’s country soul classic, “We Had It All.” Though a bit jarring in contrast with the sparse arrangements on the previous tracks, “We Had It All” showcases Jennings’ vocal power at its best.

With solid sales and radio play, Jennings was confident going into the sessions for the 1974 album This Time. Enlisting Willie Nelson as producer, occasional guitarist and songwriter, Jennings and the Waylors lay into this set of songs with a laid-back, funky groove a million miles away from the assembly line productions Music Row had been turning out. The album starts with Jennings’ own title track, full of jangly guitars and wailing harmonica, then moves on to like-minded traveler JJ Cale’s “Lousiana Women,” with some tasty Wurlitzer piano courtesy of Mrs. Jennings, Jessi Colter. Jennings revisits the Shaver songbook for “Slow Rolling Low” and takes on a couple of Nelson’s tunes, “Heaven or Hell” and the gorgeous “It’s Not Supposed to Be That Way.” Colter contributes the moving “Mona,” and Lee Clayton’s “If You Could Touch Her At All” brings the album to a close. The album has the sound of a tight group trading licks and ideas off each other, playing live and spontaneous in a small room, every note from the heart. This is Jennings and crew at their most comfortable and self-assured.

These three records took the world by storm, brought on the “outlaw” country craze and put Waylon on a first name basis with every household in America. After the song “This Time” gave him a bona fide No. 1 hit single and an exciting appearance on Don Kirshner’s Rock Concert put him in living rooms across the country, his next couple of records were set up for success. 1974’s The Ramblin’ Man, though a bit slow moving, contains three strong singles in “Rainy Day Woman,” “Amanda” and the title track. The following year’s stronger Dreaming My Dreams, full of great songs written by Roger Miller, Billy Ray Reynolds, Bob McDill and others, contains a trio of powerful Jennings originals. “Are You Sure Hank Done It This Way,” arguably the most famous of the lot, tells the tale of survival in the modern music biz over a rocking groove. “Bob Wills Is Still the King” is a call for historical reverence, and “Waymore’s Blues” is a Jimmie Rodgers-style romp with some raunchy lyrics. All three are classics, though they marked the beginning of an unfortunate trend of self-mythologizing.

In 1976 RCA released a compilation titled Wanted! The Outlaws that combined older tracks by Jennings, Nelson, Colter and Glaser. It was an attempt to use the “outlaw” brand to sell this new kind of country music to the trend-hopping public. In doing so it trivialized the message of the better songs and brought on the demon of celebrity to Jennings and Nelson in particular. The LP became the first platinum-selling country record, suggesting in some ways that the battle that had started 10 years earlier with Jennings’ first record was officially over.

Jennings had come to Nashville a pompadoured nightclub sensation fresh from Phoenix, Ariz., where he’d dipped his foot into the big time with an album on Herb Alpert’s fledgling A&M label. Don’t Think Twice, which disappeared quickly but was reissued in 1970, was aimed at the folk market and denied Jennings’ obvious country leanings. Making the move to Music City to work with Chet Atkins, Jennings would suffer a different problem. In 1965 country music was in a crisis. Rock ’n’ roll had taken much of the rural youth audience, and in an attempt to sustain adult listeners, producers like Atkins and Owen Bradley had created a slick, string and chorus-laden style tagged “the Nashville Sound.” While this method worked for some singers like Don Gibson, Jim Reeves and Patsy Cline, Jennings was a different animal. A West Texan raised on the hard country of Ernest Tubb and Carl Smith, tutored in the big beat rockabilly of Buddy Holly and inspired by the conscience-expanding sounds of the Beatles and Bob Dylan, Waylon had developed into a guitarist, arranger, writer and vocalist with a distinct musical vision. It would be through fighting against the strains of country music conformity that Jennings would come into his own.

Folk-Country (1966), Leavin’ Town (1966), Love of the Common People (1967), Hangin’ On (1968), Jewels (1968) and Just to Satisfy You (1969) are all decent albums containing a series of hit singles performed by a stylish crooner. For an artist of lesser potential, these albums would be career-defining high points, but they fall short of the hard edge Waylon would become known for. As the ’60s came to a close, the hard-touring Jennings would find himself reaching an audience outside the so-called “silent majority” country music was aiming for. On the Navajo Reservation around Gallup, N.M., his single “Love of the Common People” would become a breakout hit, providing him with super-star status in the desert Southwest. Boosted by the airplay and sales, and lifted up by his recent marriage to Colter, a first-rate singer, writer and pianist herself, by the end of the ’60s Jennings’ records began to reflect his own distinct vision. 1970’s Singer of Sad Songs, produced by pop-music guru Lee Hazlewood and featuring Tom Rush’s “No Regrets,” the Stones’ “Honky-Tonk Women” and a rocking run through Fats Domino’s “Sick and Tired” with Duane Eddy guitar licks, ’71’s The Taker/Tulsa, with a slew of hard-hitting Kristofferson tunes, and ‘72’s Good Hearted Woman, featuring Chip Taylor’s “Sweet Dream Woman” and Tony Joe White’s “Willie and Laura Mae Jones,” were all anchored with pumping bass, tough guitar picking and solid song selections. Ladies Love Outlaws (1972), with its soulful take on Hoyt Axton’s “Never Been To Spain” and a half-time, funked-up take on Buck Owens’ “Under Your Spell,” would also introduce the outlaw image via Lee Clayton’s anthemic title track. Though these albums are bogged down with older, incongruous tracks tossed in between the strong material, they are definite signposts of what was to come.

Road weary, amphetamine damaged and burned out, Jennings nearly quit the business before renegotiating his contract and seizing creative control to make his classic albums of the early ’70s. But after Wanted! The Outlaws, he found himself working through the burdens of celebrity. The tight-knit core that had harmoniously grooved through This Time had disbanded, and Jennings put together a band that was geared more to rocking the stadiums. Are You Ready For the Country (1976) featured songs by Neil Young and the Marshall Tucker Band alongside the heartfelt “Old Friend,” a moving tribute to his mentor Buddy Holly. Ol’ Waylon(1977), with its giant hit, “Luckenbach, Texas (Back to the Basics of Love),” had less rock ’n’ roll but some touches of weirdness in Jimmy Webb’s “If You See Me Getting Smaller” and the unfunny “Think I’m Gonna Kill Myself.” A duet album with Nelson, 1978’s Waylon & Willie, the same year’s I’ve Always Been Crazy and 1979’s What Comes Around Goes Around, featuring a hard-rocking run through Rodney Crowell’s “Ain’t Living Long Like This” with a disco bass line, rounded out the ’70s.

The ’80s began with Music Man, a strong collection of songs including JJ Cale’s “Clyde” and Jennings’ television hit, “Good Old Boys (Theme From The Dukes of Hazard).” Black on Black (1982), It’s Only Rock ’n’ Roll (1983), Turn the Page (1985) and Sweet Mother Texas (1986), along with duet albums with Colter and Nelson (again) and other celebrity projects finished up Jennings’ tenure at RCA. While these albums don’t come close to reaching the energy and quality of his classic period, there are good points throughout — though his choice of covers at the time was a bit disappointing. Takes on songs by Steely Dan (“Do It Again”), Gerry Rafferty (“Baker Street”) and Fleetwood Mac (“Rhiannon”) are better than expected, but at a time when roots rockers like Jason and the Scorchers, X, the Blasters and Lone Justice were turning out first rate tunes inspired by Jennings and his contemporaries, it would’ve been a great time for him to look to them for material. He actually did do just that on 1985’s Will The Wolf Survive, which is notable for the Los Lobos title track and Steve Earle’s “Devil’s Right Hand.” Unfortunately, the rest of the album is made up of Nashville songwriter tunes and the thin, early digital production sounds dated. He wrapped up the ‘80s (and his short stint with MCA) with Hangin’ Tough (1987), A Man Called Hoss and Full Circle (1988). Though hitting with a couple solid singles, including the No. 1 hit “Rose In Paradise,” these albums don’t stand the test of time. The highpoints were collected by MCA as New Classic Waylon.

Moving to Epic Records in the ‘90s, Jennings delivered 1990’s The Eagle, featuring the silly hit single “Wrong,” another duet album with Nelson, 1991’s Clean Shirt, and 1992’s Ritchie Albright-produced Too Dumb For New York City, Too Ugly For L.A. With an autobiography on the shelves in 1994, he then returned to RCA for the Don Was-produced Waymore’s Blues (Part II). Sidemen associated with Tom Petty and John Mellencamp provided an atmospheric backdrop on 10 good original songs and a Tony Joe White cover. Waylon joined Nelson and Billy Joe Shaver at Randall Jamail’s Justice Records for 1996’s Right For the Time, the most acoustic oriented project of his long career. His last studio album, 1998’s Closing In On the Fire, was cut for the ARK 21 label and contained contributions from Sting and Sheryl Crow. The last Jennings project to be released before he succumbed to diabetes-related illness in February of 2002 was a live album, Never Say Die, that featured contributions from his longtime sidemen and friends like Albright, Jerry Bridges and Reggie Young. At this point covering songs like Dobie Gray’s “Drift Away” and jamming on mellowed arrangements of his hits, it was obvious Waylon was more interested in spending time playing with his pals than creating the kind of earth-shaking music he was famous for.

Now eight years after his death, Waylon Jennings’ musical vision lives on, stronger than ever. His son, Shooter Jennings, put together a remix album, Forever Waylon, with his band adding their hard-rock sound to re-recorded Waylon classics. And of course you can always hear plenty of Waylon music played live in bars and festivals, not only across Texas and America, but around the world. Just this summer, Texan Weldon Henson played “Waymore’s Blues” and “Mental Revenge” at the Mirande Country Music Festival in France. Mario Escovedo, the hard-rocking younger brother of Alejandro, plays “Just To Satisfy You” every week with his band at the Riveria Supper Club in San Diego, Calif., and soul songstress Shannon McNally cut “Lonesome, On’ry and Mean” and “Freedom to Stay” on her last record, Coldwater. And 2003 saw the release of two all-star Waylon tribute albums. Dualtone’s Lonesome, On’ry and Mean (A Tribute to Waylon Jennings) has contributions by Kristofferson, Robert Earl Keen, Guy Clark, Nanci Griffith, Alejandro Escovedo and even punk rocker Henry Rollins, while RCA’s more mainstream I’ve Always Been Crazy: Tribute to Waylon Jennings features John Mellencamp, Dwight Yoakam, Metallica’s James Hetfield and Kenny Chesney with Kid Rock.

As for the originals, even a diehard Waylon fan would have to admit that there are way too many (“Waymore?”) albums to comfortably digest. My best advice for conquering the catalog is to pick up those three iconic albums made in the early ‘70s — Lonesome, On’ry and Mean, Honky Tonk Heroes and This Time, all of which are readily available on CD. To hear what was happening with Jennings on the bandstand at the time, grab a copy of the re-issued and expanded Waylon Live, recorded in Austin and Dallas in 1974. Next, go to Sony/BMG’s fantastic four-CD box set, Nashville Rebel. I don’t agree with all the choices on the track list, but it is an excellent overview of Jennings’ career, especially in covering the early RCA material that was scattered over so many LPs. After getting started with those, if you still want to dig deeper into the Jennings catalog, you’ll find that some of the early albums have been packaged as double CDs, and several are available for budget prices. If you have a turntable, grab every piece of Waylon vinyl you see; some albums may be disappointing or dated, but I promise there is something good on every one of them. Get out there and do some listening.

MR. RECORD MAN’S TOP 5 WAYLON ALBUMS (BY ERA)

Early Years

Early Years

Leavin’ Town, RCA 1966

Waylon’s second RCA album has more of the untamed spirit lurking beneath Chet Atkins production. Excellent songs like the title track, Gordon Lightfoot’s “For Lovin’ Me” and Delbert McClinton’s “If You Really Want Me To I’ll Go” feature some gutsy Bakersfield-via-West Texas guitar lines, while Jennings’ signature baritone croon shines.

Pre-Outlaw Years

Pre-Outlaw Years

The Taker/Tulsa, RCA 1971

Jennings’ sound toughens up considerably on four Kris Kristofferson tunes mixed in with Red Lane’s rocking “Mississippi Woman,” Wayne Thompson’s dramatic “Tulsa” and Waylon’s own “You’ll Look for Me.” The anti-war “Six White Horses” is chilling. The downside? A couple of tracks obviously recorded years earlier on the second side, including a could’ve/should’ve-been-great but unfortunatlely overproduced version of Don Gibson’s bluesy “Legend In My Time.”

Classic Period

Classic Period

Lonesome, On’ry and Mean, RCA 1973

Lean, mean and hungry, this is Waylon firing on all cylinders. Great songs, inspired guitar and pedal steel exchanges and — at last! — the voice captured in all its glory. Though comprised of other writers’ material, the album holds together as a piece chronicling the life of a drifter approaching middle age.

The Celebrity Days

The Celebrity Days

Dreaming My Dreams, RCA 1975

Neil Diamond did the liner notes for this one, announcing Jennings’ acceptance in the mainstream entertainment world. But don’t worry — the music inside contains plenty of great moments for the hardcore fans. There’s lots of guitar boogie on Billy Ray Reynolds’ “High Time (You Quit Your Lowdown Ways)” and the macho, self mythologizing “Waymore’s Blues.” Jennings’ untouchable talent with the slow ballads shines on Allen Reynolds’ title track (later covered by the Cowboy Junkies and Marianne Faithfull), and a beautiful take on Hank Williams’ “Let’s Turn Back the Years.”

The Later Days

The Later Days

Waymore’s Blues (Part II), RCA 1994

The drop in intensity between Jennings’ classic ’70s work and his later albums is jarring. But in 1994, on the heels of his autobiography (co-written with rocker Lenny Kaye), Jennings took an inspired look through his past to come up with a set of self-penned songs (and a run through friend Tony Joe White’s cool “Up In Arkansas”) on this “comeback” album of sorts. Legend has it that when drummer Kenny Aronoff, keyboardist Benmont Tench and guitarist Mark Goldenberg gathered with producer Don Was to record the album, Jennings instructed them to forget all they knew about his musical past and just play the songs — he’d take care of the Waylon Jennings part. The album has a modern, atmospheric sound that nicely frames Jennings’ voice, and Nashville soul singer Jonell Mosser also makes some tasty contributions. “Old Timer (The Song)” is a particularly moving track about lost love and lost time. It may not be in the league of Lonesome, On’ry and Mean, but Waymore’s Blues (Part II) is a fantastic insight into the man who made those revolutionary records.

This is an insightful overview of an artist that has done a lot for what we now tend to call Americana, though I don’t like that term, roots music suits me better. It also rightfully calls to attention the beautiful records he made in the sixties, which sound better by hindsight, even the background singers have their peculiar charm, a bit dated maybe but not overpowering or untasteful, and somehow providing something nostalgic to an amazing soulful performance (even right before or during the time that Gram Parsons made it his trademark). Though in the article Dreaming my Dreams is favored over Ramblin’ Man for obvious reasons of rocking harder, I myself think the latter digs deeper and is actually the one I like most, as much as I have to admit those three that are called his masterpieces here may be artistically topping that one. But why compare? He stands beside Johnny Cash, Merle Haggard and Willie Nelson in my book, warts and all (for all of them).