By Scott Schinder

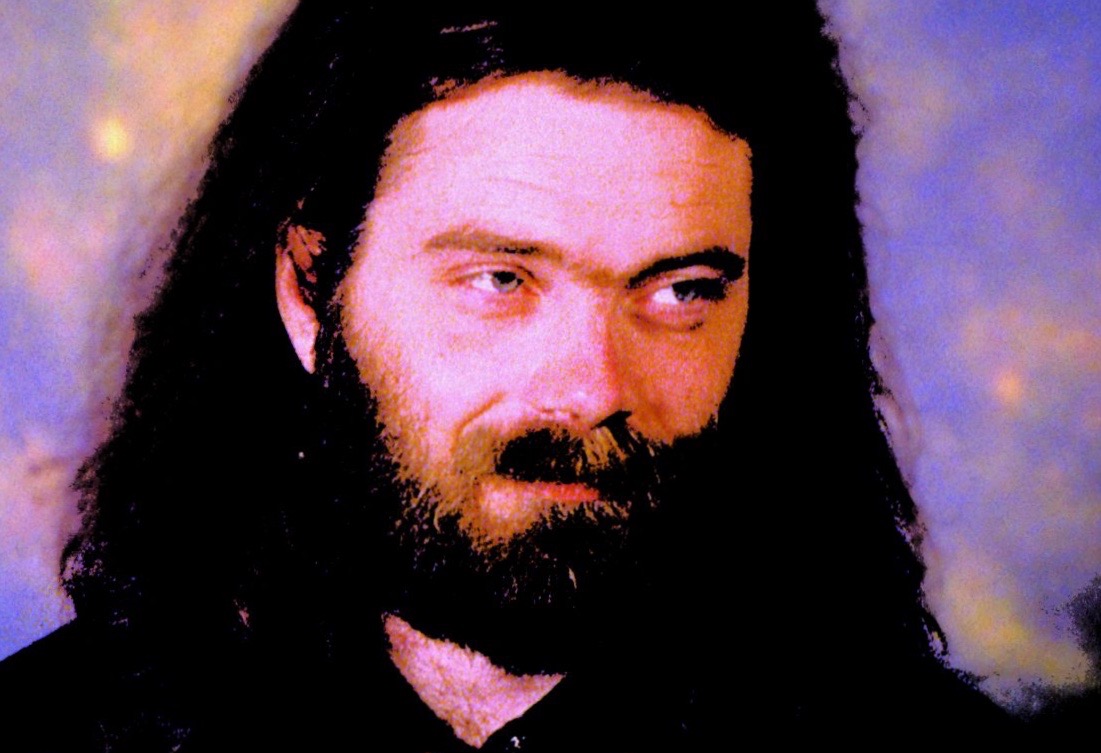

In his seven decades on this planet, Roky Erickson — psychedelic pioneer, punk progenitor, horror-rock maestro — scaled dizzying creative heights and spent extended stretches living on the margins of society. Indeed, if one were to invent the story of a tragic cult hero who failed to achieve a level of fame and fortune commensurate with his achievements and influence, it would be hard to envision a more dramatic saga than that of the Texas trailblazer.

Rock’s history is littered with the tragic life experiences of musicians who lost their way via substance abuse and/or mental illness. But Roky Erickson, who died in his longtime hometown of Austin at age 71 on Friday, May 31, was a rare instance of a visionary artist who eventually came back from the abyss to make vital music again. Along the way, he paid the same penalty extracted from many of those who’ve flown too close to the sun. He spent extended stretches of his life in personal and creative limbo, while his struggles with mental illness and drug use periodically threatened to make him a legend for the wrong reasons.

Erickson was a genuine original, and a genuine eccentric, in a field in which such terms are thrown around too easily. As lead singer, rhythm guitarist, and co-songwriter of the 13th Floor Elevators during the second half of the 1960s, he matched his wild-eyed banshee wail to Tommy Hall’s acid poetry and the band’s expansive sonic excursions. In his subsequent solo career, he plumbed the depths of his tortured soul to create uniquely powerful rock ‘n’ roll that mined horror-movie imagery to evoke the very real monsters that plagued his psyche.

During their turbulent 1965-1969 existence, the Elevators released three studio albums on the Houston-based International Artists label. Their first two LPs, The Psychedelic Sounds of the 13th Floor Elevators and Easter Everywhere, are essential classics that belong in the collection of anyone interested in psychedelia.

Psychedelic Sounds (recorded when Erickson was just 19) opens with the savage Roky-penned garage anthem “You’re Gonna Miss Me,” which became the Elevators’ only charting single, reaching No. 55 on Billboard‘s national pop chart (and charted higher in many regional markets through the Southwestern U.S.). Erickson had previously released the song as a 1965 single with his pre-Elevators band, the Spades.

The Elevators began work on a projected third studio album, reportedly under the working titles A Love That’s Sound and Beauty and the Beast, in 1968. But Erickson’s increasing drug-fueled instability helped to sideline the project. Instead, International Artists slapped together Live, a fake concert LP comprised of demos and studio outtakes overdubbed with unconvincing crowd noise and assembled without the band’s participation. The Elevators — some of them, anyway — eventually managed to make a final studio album with 1969’s Bull of the Woods. But Erickson was in no condition to contribute creatively, and only appeared on four tracks salvaged from the unfinished A Love That’s Sound/Beauty and the Beast sessions.

By the end of the ’60s, the 13th Floor Elevators had crumbled, the victims of their own chemical excesses as well as a campaign of police harassment directed against the band, whose open advocacy of controlled substances made them an inviting target. In 1969, Erickson was arrested for possession of a single joint — at the time, a felony that carried a possible 10-year prison sentence.

Pleading not guilty by reason of insanity in order to avoid prison, Erickson was committed to the Rusk State Hospital for the criminally insane, where he spent three nightmarish years amongst murderers and rapists, and received electroshock and Thorazine treatments. During his stay, he formed a band with some fellow inmates, wrote a book of mystical poetry entitled Openers, and composed numerous songs. When he was finally released from Rusk in 1972, Erickson was a changed man, with many friends and family members agreeing that treatments he received at Rusk exacerbated whatever psychological problems he may have had before entering.

After a brief attempt to reform the Elevators, Erickson reemerged with a hard-rocking new band, Bleib Alien, later known as Roky Erickson and the Aliens. The new outfit complemented Erickson’s feral howl and raw, melodic new songs, whose references to horror movies and supernatural phenomena turned the demons, zombies and vampires that haunted him into unmistakably personal music and engaging, asymmetrical lyrical wordplay.

Erickson returned to the studio with help from longtime admirer and fellow Lone Star iconoclast Doug Sahm, who financed and produced an indie single containing the harrowing “Red Temple Prayer (Two Headed Dog)” and the yearning, Buddy Holly-esque “Starry Eyes.” That disc was followed by a scattershot assortment of releases that compellingly showcased Roky’s new horror-rock vision, even if few people heard them.

In 1979, Roky and the Aliens recorded 15 tracks in San Francisco with Creedence Clearwater Revival bassist Stu Cook producing. Those sessions would produce some of the most lucid music of Erickson’s checkered career, trading the Elevators’ spacy sound and philosophical lyrics for jagged garage-rock sonics, compact melodic craft, and cartoonishly cathartic lyrics encompassing many of the songs that would comprise the core of his repertoire for years to come. Such tunes as “Creature with the Atom Brain,” “Night of the Vampire” and “Bloody Hammer” feature unusual, indelible hooks and oddly poetic turns of phrase.

Incredibly, in 1980, much of the Cook-produced material formed the basis of Roky’s first official solo album and first-ever major-label release — at least in Britain, where CBS issued the album, informally known as “Runes” or “Five Symbols” for its untranslatable cover characters. Many of the Cook tracks also appeared on the album’s American counterpart, released by the indie label 415 the following year as The Evil One.

The release of numerous archival Erickson packages, most of them assembled without the artist’s input, in the ’80s and ’90s demonstrated the growing public interest in the artist’s work. As it happened, though, Roky retreated from music-making for a decade during this period, becoming reclusive as his mental and physical health continued to deteriorate.

Word of Erickson’s difficulties reached old friend and Warner Bros. Records exec Bill Bentley, who responded by assembling the 1990 tribute/benefit album Where the Pyramid Meets the Eye: A Tribute to Roky Erickson, which features a wide array of memorable interpretations of his songs by the artist’s contemporaries (ZZ Top, Doug Sahm) and acolytes (R.E.M., Julian Cope, the Jesus and Mary Chain).

The tribute disc helped to set the stage for All That May Do My Rhyme, released in 1995 on Butthole Surfers drummer King Coffey’s Trance Syndicate label. Promoted as Roky’s first new album in a decade, it actually combined five new, demon-free tunes, with the contents of the 1985 EP Clear Night for Love. The result was surprisingly cohesive, showing Erickson to still be capable of crafting fetchingly elliptical pop tunes that reflect compellingly on his own travails.

Erickson’s living situation improved substantially in the 2000s, as he received much-needed medical care and legal aid and eventually made an unexpected return to touring. 2005 saw the release of the career-spanning double-CD collection I Have Always Been Here Before: The Roky Erickson Anthology, followed in 2007 by Kevin McAlester’s revealing Roky documentary You’re Gonna Miss Me. The same year, Erickson, one of rock’s most notorious burnouts, defied expectations by returning to the stage not just for special appearances in his hometown of Austin, but for festivals, theaters, and clubs across the country and beyond.

In 2010, Erickson surprised fans once more with the release of True Love Cast Out All Evil, his first set of new recordings in a quarter-century. Produced by Okkervil River leader Will Sheff and featuring Sheff’s band as backup, the album rescued a set of intimate ’70s compositions, most of them written during Roky’s stay at Rusk, to create an affectingly reflective song cycle. With Erickson singing sensitively arranged songs of God, freedom, and bottomless loss in a frayed, vulnerable voice, True Love Cast Out All Evil was terrifying, touching and ultimately triumphant, expanding Roky’s remarkable legacy in ways that would have been unimaginable just a few years earlier.

Roky Erickson spent his last dozen years reconnecting with family life and continuing one of the most unlikely comebacks in rock history. Financially secure for the first time in decades, he toured successfully throughout the United States and overseas, performing his classics for crowds of adoring admirers, most of whom weren’t born when the 13th Floor Elevators first explored inner space. In death, his unique vision continues to burn brightly.

No Comment