By Rob Patterson

(LSM Oct/Nov 2014/vol. 7 – Issue 5)

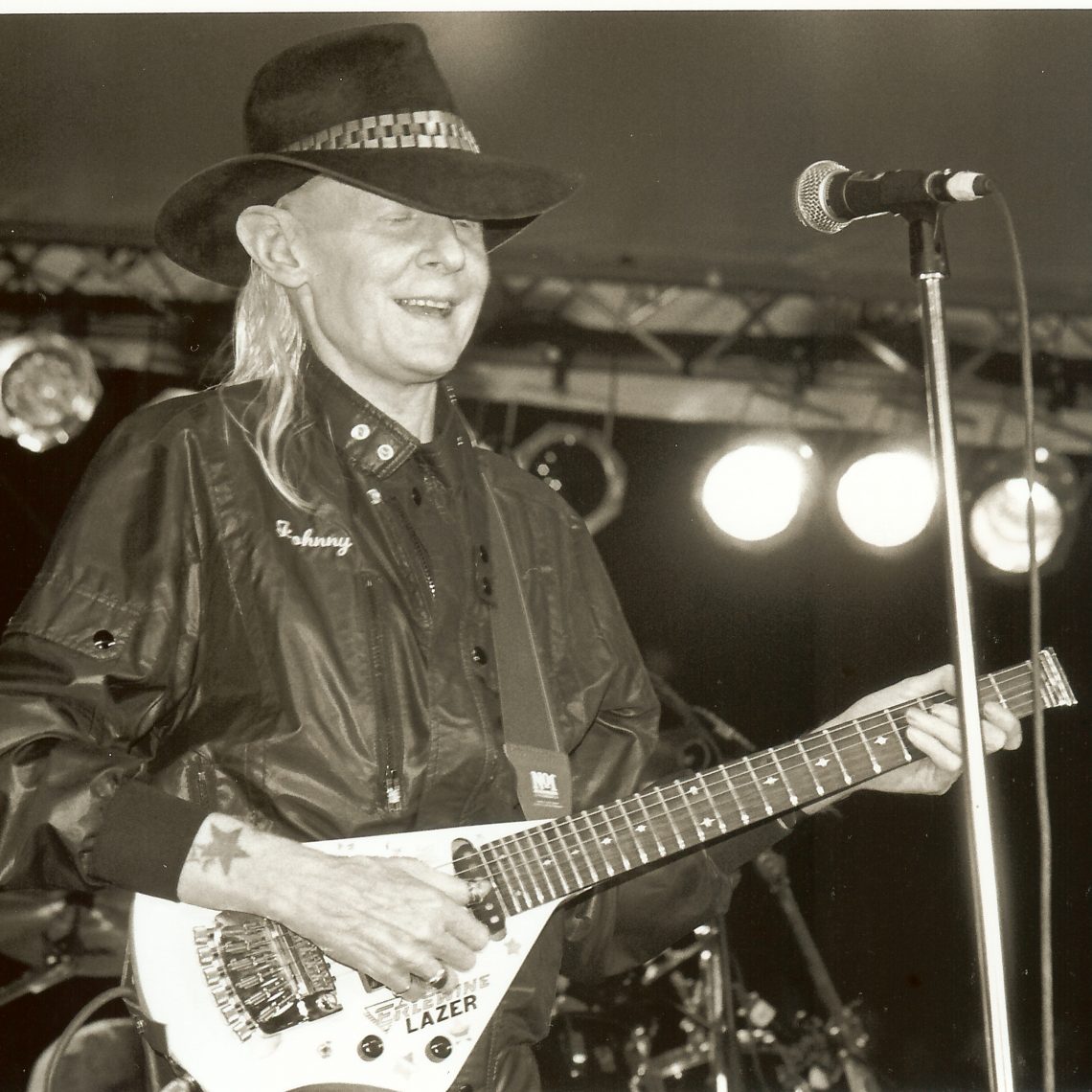

One feels just a twinge of guilt to say there is an upside to the passing of some significant musical artists. But the recent death of Texas blues guitar wizard Johnny Winter on July 16 at 70 years old makes the case that when influential musicians long out of the mainstream spotlight depart this earthly realm, it can and does help reassert why they matter and the impact they had on popular music.

It’s not totally like “you had to be there” to understand. But when Winter emerged from Texas onto the international music scene in the late 1960s, white musicians playing blues guitar for a rock audience was still something rather new since the emergence of blues-influenced British rock bands like the Rolling Stones, Animals, and Yardbirds a few years before. Guitarists like Winter, Eric Clapton, Jeff Beck and Mike Bloomfield upped the ante with their fleet-fingered extended workouts and fiery tone. What distinguished Winter was how fully-steeped his style and sound was in genuine blues and the ferocity of his musical attack. Even the highly- regarded Bloomfield, who learned his craft on the South Side of Chicago — ground zero for black urban blues — hailed Winter as the best of the white blues players.

Winter leapt to fame in 1968 by bringing a crackling intensity to the electric blues canon with the independent Progressive Blue Experiment, recorded at Austin’s legendary Vulcan Gas Company nightclub on a night it was closed. He followed it lightning quick in 1969 with his self-titled major label debut on Columbia Records, for which he was paid a reportedly then-unprecedented $600,000 advance. Both Johnny Winter and Second Winter, a three-sided LP released later that same year, proved he could translate the blues tradition into a rock ’n’ roll mode. A Rolling Stone cover story and his appearance at Woodstock helped make Winter a star through the 1970s.

Born in Beaumont in 1944, both Johnny and younger brother Edgar were encouraged in music by their parents. “An albino in ever-so-conservative Beaumont was going to stand out,” says noted music photographer Stephanie Chernikowski, who went to the same schools as Winter, who was a few years younger than her, and first heard him play when she was in high school. She says that even from a young age, “the Winter brothers were known as accomplished musicians and recognized as ‘others’ in a community that was not fond of others.”

Jon Paris, a skilled blues guitarist and songwriter himself who played bass with Winter throughout the 1980s, recalls Winter talking about feeling ostracized as a youth. “Johnny told me how he and Edgar were just treated like crap in school,” Paris says. Where Winter did find acceptance was, ironically, in Beaumont’s black music clubs he began to frequent as a teen.

He’d obviously learned his lessons there well when Chernikowski heard him again in Austin in the mid ’60s. “He’d come a long way, and he was awesome,” she recalls. A Winter show this writer saw in New York City in the late ’70s was not only stunning for his searing guitar work-outs, but also for how he performed with such intensity that at the end of the show, soaked in sweat, Winter had to be all but carried offstage by his road manager. He literally gave everything he had to playing his music.

“He was just a well of musical knowledge,” notes Paris. “He is rightly known as a blues master, but he was an all-around phenomenal musician. He was a man on a mission to show the world what he could do.”

Dropped from Columbia after his last record for the company in 1980, Winter carried on recording for the independent Alligator label and consistently touring. “All of us around Johnny when I was working with him in the ’80s used to say to him: ‘Johnny, why don’t you try and have a hit record, what’s so bad about that? Do a good rocking tune and try to get a hit. Then when we get out to play you’re going to have more people come that you can lay the blues on,’” says Paris. “At the time it seemed like a no- brainer: Guys like Clapton, ZZ Top and the Fabulous Thunderbirds were having hits and then getting up onstage and playing the blues.

“He said, ‘Oh no, if I have a hit record, all my blues fans will desert me,’” Paris continues. “He was so into being a blues purist and respecting the genre.”

During the height of his fame in the ’70s, Winter produced three excellent albums for Muddy Waters that won the blues legend Grammy Awards and ushered in the most successful years of his career. Winter’s hard-driving style and three-man band was an obvious influence on Stevie Ray Vaughan when he formed Double Trouble with former Winter sideman Tommy Shannon on bass.

Winter died as he lived, in a hotel room on tour in Europe. Sadly, it was just after issuing a three-disc career retrospective box set, The Johnny Winter Story, and less than two months before the release of a new album, Step Back, that features guest appearances by Billy Gibbons, Eric Clapton, Ben Harper, Dr. John, Joe Perry, Brian Setzer and others.

“It’s now a moment for celebration of his brilliance frozen for all time,” says Gibbons of Winter’s passing. “We’ve lost another of the gifted guitar greats and a truly soulful spirit.”

“He once told me how when he was a kid, he wanted to be the best blues guitar player in the world — that was his goal,” says Paris. “And he certainly is in the minds of a lot of people. Nobody could play like him. He was just unbeatable.”

Johnny Winter had a true spirit about his music. That is what drew me to his music.