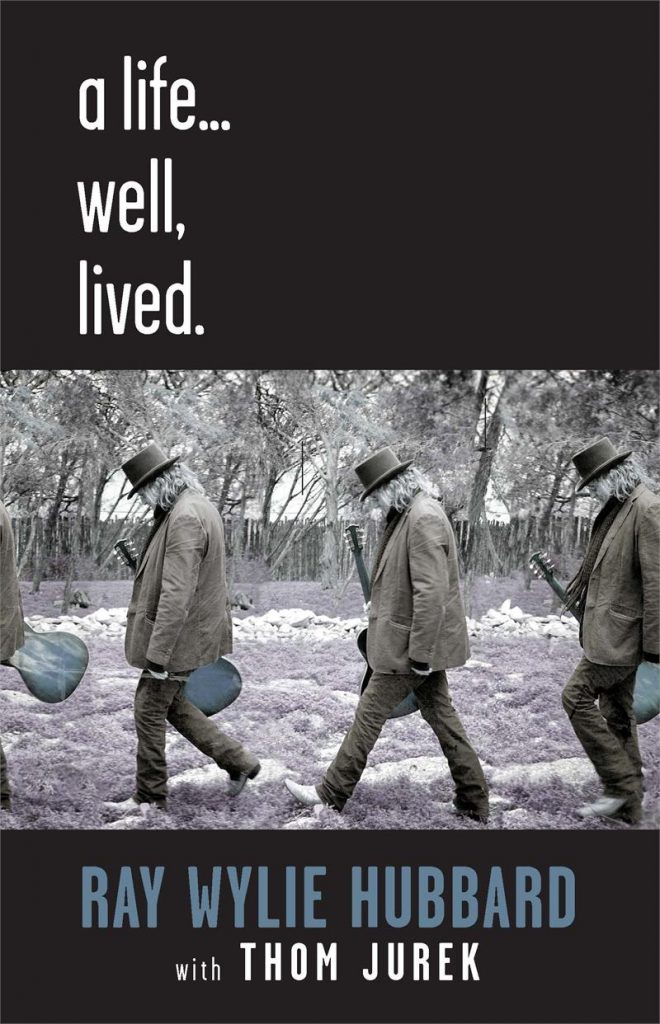

a life … well, lived

a life … well, lived

By Ray Wylie Hubbard with Thom Jurek

Bordello Records

By D.C. Bloom

The epigraph speaks volumes.

Ray Wylie Hubbard chooses the diametric yin and yang of Greek tragedian Aeschylus and his wife, Judy Hubbard, to signal just where he’s going with his new autobiography, a life … well, lived. The spiritual grounding the author — and yes, let’s refer to Hubbard not as one of Texas’ most brilliant songsmiths for the moment, but as a figure of ample literary prowess — finds in both the wisdom of the elders and the commonsensical perspective of a good Texas woman provides a revealing clue as to where Hubbard has drawn inspiration and hope throughout a fascinating and well-lived life.

Interspersed, as it is, with lyrics from a host of Hubbard songs, a life … well, lived plays (sorry, reads) like an extended Ray Wylie set with an extra generous serving of his trademark Okie-infused aw-shucks revelatory stage banter, which owes as much to Will Rogers as it does to Woody Guthrie.

So there are breezy stories about Hubbard’s late-night network television appearances with Jimmy Fallon, Conan, and David Letterman (who made a special request of RWH to play “Screw You, We’re From Texas” for his studio audience during a commercial break); Ringo Starr’s love of Snake Farm and RWH’s mutual admiration for the Liverpudlian percussionist’s “Coochy Coochy”; a pins and needles post-gig robbery in an L.A. Howard Johnson’ parking lot and Little Richards’ “Lawdy Clawdy” take on same; a memorably hazy bit of space and time traveling on Willie’s bus to a beerfest in Milwaukee; and what Hubbard still calls the best gig of his life at the Texas Redneck Games near Tyler in front of hundreds of hard-drinkin’ and cow pasture copulatin’ redneck brothers and sisters.

Along the way, Hubbard also writes about the redneck family and matriarch that inspired that oft-performed and enthusiastically sung-along song of his about honky-tonkin’ Okies who take wives with names like Betty Lou Thelma Liz. And there are compelling cameos from luminaries such as Mance Lipscomb, Bob Livingston, Tony Joe White, Terry Buffalo Ware, Gurf Morlix, Dallas Cowboy Pat Toomay, Troy Campbell, Ronnie Dunn sans Brooks, Jerry Wexler, Jerry Jeff Walker, and Hubbard’s own guitar-slinging son, Lucas. A fair chunk of the first half of the book finds him revisiting colorful times as a young musician working summer residencies, for lack of a better word, in not-so-glamorous venues in New Mexico and Colorado, where he and his band were recruited with the promise of a peak season influx of big-breasted farm girls from Texas and Oklahoma seeking harmonic attention from young musicians just like them.

But for all the hilarity and music history contained in a life … well, lived, the strength of this incredibly easy read are the accounts of the off-setting deals Hubbard has made with the devil of drink and the heavenly father of forgiveness over the years. From an early childhood accidental stoning of an Oklahoma cousin to an adolescent encounter with a stubborn pair of balls that just wouldn’t drop to a teenage bender after his first of beer to his realization that it’s way beyond time to give up the bottle, Hubbard isn’t shy about recounting the promises he’s made to that higher power that he’ll straighten up and fly right, if he’s only granted another chance. There’s many a candid confession here from an imperfect layman who continually believes in the saving grace of deal-making redemption.

But when Hubbard learns, at the young age of 29, that he has pancreatitis and is forbidden from drinking ever again, there’s a really big, life-or-death deal to be made. No punches are pulled about the reticence Hubbard had about giving AA a go and working the 12-step program. As one would expect from one of Texas’ most honest songwriters and performers, Hubbard offers a frank and revealing look at the struggle of pulling oneself out of the grip of alcoholism and forging a sober will to not only survive, but thrive in a business where the temptations to hop off the wagon are many and close between.

Hubbard also plays the sage career and songwriting advice giver towards the end of the book. To aspiring artists, he suggests “there’s a fine line that does not need to be crossed as far as getting your songs heard and that line is the difference between being persistent and being a pest. However, it’s okay to promote yourself … just don’t let anybody see you do it on purpose.” And he even reveals the secret of his own stellar career, if not of the universe itself: “It’s an E chord without the third … repeat … it’s an E chord without the third.”

So go get yourself a chord book … and a life, well, lived.

No Comment