By Richard Skanse

It’s not about nostalgia, Terry Allen insisted. “It’s about memory.”

That was mid-December, and the internationally renowned artist, sculptor, and maverick songwriter was sharing his creator’s thoughts on the meaning of “Road Angel,” the bronze-casted, song-and-story-playing ’53 Chevy coupe he was about to unveil at Austin’s Laguna Gloria museum and sculpture garden. But he could have just as aptly made the very same point at the outset of his concert last Saturday night at the Paramount Theatre, which was billed as a celebration of Juarez and Lubbock (on everything), Allen’s 1975 debut and its even more acclaimed 1979 follow-up. Long regarded by songwriting connoisseurs as seminal entries in the Texas music cannon, both albums were reissued last year in exquisite fashion by the boutique record label Paradise of Bachelors, and Allen’s Austin show was just the first of several dates he’ll be playing this year to help support the re-releases. But don’t misconstrue any of that for laurel resting, let alone trading in nostalgia for the sake of easy crowd pleasing. Allen may be a renaissance artist of the highest order, but “safe” has never been in the guy’s wheelhouse. And as anyone even remotely familiar with his vast body of work should know, he doesn’t exactly do “comforting” very well, either. Suffice it to say that even though the double-album sprawl of Lubbock may betray the odd hint of sincere affection peeking through the chinks in Allen’s satiric armor, nobody in the 42 years since its release has ever turned to Juarez for a purely nostalgic warm fuzzy fix.

“Memory,” though — well, that’s another matter. Playing with memory has always been fair game in Allen’s book. Where nostalgia looks back with a wistful sign and holds fast, memory mutates over time and shapes the present. Rare as it may be to hear Allen perform all or even most of the songs from his first two albums in sequence like he did on Saturday, a fair lot of them have long been staples of his live repertoire — which accounts for why he says he’s personally never thought of them as being “old” in the first place. “They were written a long time ago, but to me, it’s like songs have a kind of eternal life to them,” he explained in December. “I’ve played those songs on and off for years, and every time you sing one it’s different, because every situation is different. And I think you always find some kind of meaning in them that you didn’t expect before.”

Juarez in particular has always been ripe for reinterpretation and discovery. A blood-splattered road-movie-cum-corrido conflating multiple characters, geographic locations, eras and even centuries into a willfully enigmatic, Möbius strip of a so-called “simple story,” it seems to reveal new meaning and mysteries with every visitation. Not for nothing does Allen himself call Juarez “a haunting.” In a 2013 interview with Lone Star Music, he likened it to a flying saucer that came into his life and “kind of changed everything for me. … There were so many surprises with Juarez, half the time I couldn’t wait to find out what was going to smash me in the head next!”

It’s been smashing him on and off now for going on 50 years, spawning not just the original album but the equally intense series of vivid drawings that preceded it, a subsequent theater piece, and of course Allen’s recurring habit of re-recording a different Juarez song on almost all of his later albums (with Lubbock being the most notable exception.)

Needless to say, pulling those songs out of their original context only heightens their mystery — especially for anyone hearing them for the first time sans the album’s expository dialogues or any formal introduction whatsoever to Sailor, Spanish Alice, Jabo, and Chic Blundy. Regardless, songs on the level of “Four Corners,” “What of Alecia,” “Cantina Carlotta,” “There Oughta Be a Law Against Sunny Southern California” and especially “Cortez Sail” hold their own in any setting, and the practice has also allowed Allen the opportunity to reimagine them with fuller instrumentation; for the most part, the 1975 recordings — tracked in California before the prodigal Texan’s Lubbock homecoming — featured only Allen’s piano with minimal flourishes of guitar and mandolin. Whether one approach is “better” than the other has always been a matter of personal taste, but Saturday night at the Paramount, fans finally got a chance to hear the whole Juarez story given that alternate richer, technicolor treatment from start to finish, courtesy of Allen and a particularly luminous all-star permutation of his Panhandle Mystery Band. Regrettably, due to the need to budget equal time for (almost everything on) Lubbock in the second half of the show without breaking the venue’s strict union curfew, Juarez side-one stunners “Writing on Rocks Across the USA” and “The Radio … and Real Life” apparently drew the short straws at rehearsal and were left behind. But as essential as both of those songs may feel on the actual record, the rest of the set proved so mesmerizing that their absence was barely even noticed until intermission. Because from the very first notes of “The Juarez Device” (aka “Texican Badman”) through to “La Despedida” (followed by the non-album but same-vintage “Wilderness of This World”), that old “tragic magic” was very much in the house, swelling loud and clear all the way to the back of the top balcony.

As befit such a special occasion, the cast was spectacular. Pedal steel maestro Lloyd Maines (no slouch this night on acoustic and electric guitar, either) and gonzo fiddle/mandolin player Richard Bowden may not have been in Allen’s orbit yet back when Juarez was recorded, but both have been mainstays of the mercurial Panhandle Mystery Band from Lubbock on. Bassist Glenn Fukunaga and drummer Davis McLarty entered the Allen universe sometime later but have been part of his trusted musical family for years — as have, quite literally, his sons Bukka (accordion) and Bale Creek Allen (bongos). Guests Charlie Sexton (acoustic and electric guitar) and Ryan Bingham (mandolin and vocals) joined the fray separately to special introductions and excitable applause a few songs into the set, but within moments both were fully integrated into the band as though they’d been there from the start.

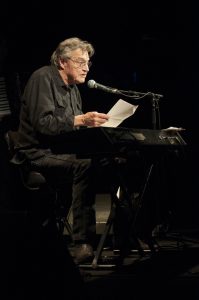

For all that formidable talent around him, though, it was Allen, dressed in black and seated front and center behind an electric keyboard, who was very much the prime mover all night long. His raspy boom of a voice, equal parts coyote howl, arch sneer and elemental West Texas fury, filled the theater with almost supernatural ease, as did the primitive rhythmic roll and conquistador-bold stomp of his piano playing, which for most of the Juarez songs featured a synth setting that imbued every haunted chord and pounded note with a spectral, otherworldly glow. All that the rest of the players onstage really had to do was keep up — or more appropriately for the first set, respectfully hold back. Although every instrument in the mix — Bukka’s Tex-Mex accordion, in particular — added gorgeous layers of sonic depth and ambient light and shade to the Juarez material, only the hot-and-bothered “Border Palace” and psychopathic rampage of “There Oughta Be a Law Against Sunny Southern California” called for (and duly received) the full-on pedal-to-metal, asphalt-into-brimstone treatment. Everyone knew there would be opportunities aplenty for jaw-dropping solos and fireworks come Lubbock’s turn in the spotlight.

After a generous intermission, the band (Sexton and Bingham included) returned to the stage accompanied by another special guest, actress, writer, and storyteller par excellence Jo Harvey Allen. Having been Terry’s wife, muse, and partner in crime for all manner of art mischief for well over half a century, her playful (but ostensibly true) boast that “Terry would never be a songwriter if it wasn’t for me” went uncontested, least of all by her nodding-in-agreement husband. Among other pearls, she dismissed out of hand the notion that Lubbock’s legacy for producing so many great songwriters, musicians, and artists was a result of there simply being nothing else to do there. “If there’s nothing to do, how come we always had so much fun doing it?” she asked. “Terry knocked at my door once for a date, and he said, ‘Run for your life, they’re after us!’ And boy, we lit out running, we jumped in that car, slammed the door and he peeled off down the block, and we hid all night from ‘them.’ Now, I know Terry made that up, but we are still running from them!”

Even at nearly 10 minutes, Jo Harvey’s wry and utterly delightful monologue setting up Lubbock (on everything) was all-too short; she could have easily kept the whole crowd in stitches for the rest of the night. But the biggest Terry Allen fan in the building was as eager as anyone to hear the second act, and graciously turned the spotlight back onto her husband by ending her final anecdote with two little words that might as well have been tied up with a Texas-sized bow: “The Wolfman …” The audience whooped, Terry flashed his wife a shit-eating grin, and then tucked right into the evening’s main course.

“Well he took his first release

on a highway

in a 1953 green Chevrolet

and he was carrying an awful load

for just a 15 year old

Till he laid his mind

on the center line

and turned on the radio …”

If the aforementioned line of distinction between nostalgia and memory seems a little more blurred across wide swaths of Lubbock (on everything), it’s worth noting that Allen’s second album is by design and necessity all about perspective. Juarez may well have crashed into his consciousness from out of nowhere, sans explanation or instruction manual, but Lubbock could have only ever been written through the crystal clear lens of 20/20 hindsight. Like the first album’s Jabo and Chic leaving L.A. for Juarez by way of Cortez, Colorado (“they go north to get south”), Allen first had to get the hell out of Hub City, move all the way out to California, and spend years infiltrating the wine and cheese crowd and so-called “Art Mob” scene before finally coming back around to not only sorta appreciating his humble blue collar hometown, but hooking up with a bunch of guys from the Joe Ely Band to casually knock out the greatest record in Texas music history. (Fortunately, unlike Jabo’s journey, nobody got hurt or killed during the making of Lubbock — except of course for the poor driver of that doomed “Truckload of Art.”)

Speaking of “Truckload of Art” and “The Art Mob,” there’s a couple of other key points to make about Lubbock (on everything). First is the fact that its 21 songs cover a lot more thematic ground than just the literal Panhandle, with a good chunk of the middle of the album shifting its satirical crosshairs to the art and avant garde world that’s long been every bit as big a part of Terry Allen’s life and career as his music. Secondly, in stark contrast to the palpably unsettling, spine-tingling sense of tragedy and violence that permeates Juarez (even or especially in the pretty bits), Lubbock is a goddamn blast. And you could feel the mood change onstage and throughout the theater almost immediately. Mind, not every song on the album is necessarily funny, let alone meant to be; at times, sometimes in the span of a single line or two, they can be disarmingly sweet or downright sad. In “High Plains Jamboree,” an unhappily married family man and a gold-toothed honky-tonk woman (“she weren’t no Maid-of-Cotton”) find fleeting comfort in each other’s arms, “like only the lonely can.” “Lubbock Woman” and “Blue Asian Reds” (two of the six songs from the album that had to be trimmed from the Paramount set due to the aforementioned curfew) ache with empathy, and who’s not a sucker for every sad “cracker crunch” in “The Beautiful Waitress”? But then on a dime, like a jukebox, Lubbock cracks wise with a wicked grin and kicks back into high gear. And whenever the set took one of those turns Saturday night, every player onstage — Allen included — jumped like an excited dog let off leash. Of course you could feel the rush of “Amarillo Highway” (track one on record, but sequenced here after “The Wolfman of Del Rio” to great effect) coming from a mile way, but even that thrill was just a tease for the highlights still waiting around nearly every bend: Maines’ rocket-powered pedal steel taking flight from seemingly out of nowhere in the middle of “The Girl Who Danced Oklahoma”; the demon-possessed, gypsy-Banshee scream of Bowden’s fiddle tearing “The Collector (and the Art Mob)” a new one; Sexton’s shit-hot solo doing “Flatland Farmer” (and the late Jesse “Guitar” Taylor) proud. Not to mention Joe Ely, who hopped onboard the “New Delhi Freight Train” just to blow some furious harp, just like he did on the record 39 years ago. Allen also called both Terri Hendrix and Savannah Welch out for that one, as much just to share the fun as for their added vocal power.

“It’s great to have this stage filled with some of my oldest and greatest friends,” he enthused, visibly having as good a time as everyone else onstage. Ely, Hendrix, and Welch all left after “New Delhi,” but they weren’t gone for long. The women returned to sing spirited backup on the delightful “Pink and Black Song,” and two songs later, after Allen polished off Lubbock with an spare and solo reading of “I Just Left Myself” under a solo spotlight, Ely and the whole Panhandle family joined him for an ecstatically received joy ride home with the uproarious “Gimme a Ride to Heaven” and, finally, an entirely fitting and sincerely heartfelt “Give Me the Flowers.”

“I hope you all get your flowers while you’re living,” a beaming Allen said at the very end, taking his final bow to a full-house standing ovation. Flanked on either side by immediate family and friends old, great, and new, it was clear he got his Saturday night. And a very fine new memory, to boot.

No Comment