By Richard Skanse

February 2002

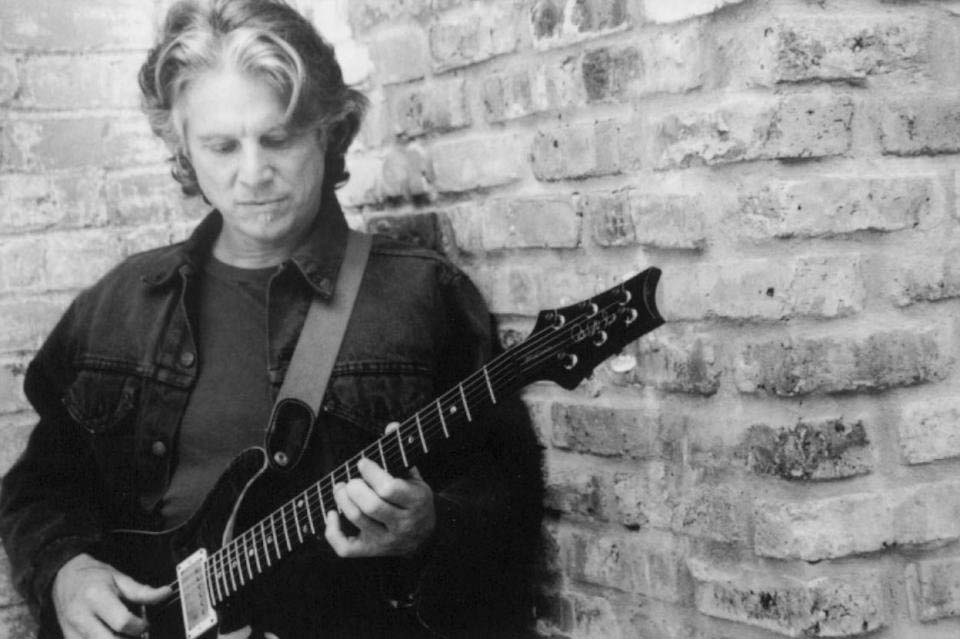

In the Texas music sideman hall of fame, Stephen Bruton can comfortably take his place amongst the A-list ranks of veteran cats like Johnny Gimble, Billy Preston, Bobby Keyes and Augie Meyers. The son of jazz drummer Sumter Bruton Jr. — who also happened to own the coolest record store in North Texas (Fort Worth’s Record Town, still standing after 45 years), Turner Stephen Bruton began playing guitar with Kris Kristofferson shortly after graduating from TCU, and he’s been “off to the races” ever since. Along the way, he’s picked up gigs with everyone from Billy Joe Shaver to Bonnie Raitt, Bob Dylan to local hero Bob Schneider … not to mention Barbra Streisand, and also done a little bit of all right for himself as a producer and songwriter. His latest adventure — apart from his weekly gigs at Austin’s Saxon Pub with the unassuming supergroup the Resentments [Bruton, Jon Dee Graham, Scrappy Jud Newcomb, Bruce Hughes, and before his passing last fall, John “Mambo” Treanor] — is that of solo artist, a singer-songwriter who happens to play killer lead guitar in a way that always serves the song over the solo. On Spirit World, his second album for Austin/Los Angeles label New West Records and his fourth solo set to date, Bruton the self-professed “wise guy” reveals his sensitive side, setting the relaxed, jazzy and introspective tone of the record for the most part with the opening beauty, “Yo Yo.” But just when he’s got you good and relaxed, he throws the snarling, Dylanesque rocker “Acre of Snakes” at you — proof that when someone’s spent a lifetime soaking up nearly every musical style under the sun like Bruton has, the best of it can break out at any time and still surprise you.

If albums have distinct personalities, how would you label Spirit World? Did you have a theme in mind throughout the project?

I never really think about a theme to an album, although I guess this one does have some sort of theme, but I don’t write with a formula in mind at all. I just go with the best songs that I’ve written at that point. I have to beg off responsibility on answering the question because I’m really the last person that could answer that. It’s like when you’re looking at an album, everyone else is looking at it as a whole and I’m looking at it as a two-year process. But I think “Spirit World” is an idea, and kind of a concept, and also kind of a visual that really kind of encompasses all of the songs on the record. John Kilzer and I were working on his album in L.A., with T Bone Burnett, and we had a little bit of time off and John and I were messing around with the idea for the song. There seemed to be so much bad news coming out that day, so much divisiveness — it seemed like race relations and every other kind of relations in the world were in worse shape than they were when we were little kids. So we were trying to write a song with a peace-love-hippie vibration, a positive message. It was just one of those days where it seemed like nothing was working, and we decided to write something different. That’s how that song came about.

Does that peace-love-hippie vibe characterize you generally, or does it take really bad circumstance to bring that out?

Well, I wouldn’t say … both. I mean, it’s kind of typical of people of my generation, but at the same time, I come up with more of the wise-guy approach. Wise-guy lyrics as my friend calls it. That’s more my style in terms of writing than some sort of misty-eyed idealist.

Speaking of misty-eyed, the last verse of “Just a Dream” is about John “Mambo” Treanor, isn’t it?

Yes. I had written that song in a London hotel room. I had woken up from a dream, and there was a TV show on, and I heard this guy on the TV say “oh, it was just a dream.” I just had this visual of this person, so I turned off the TV and I wrote this first verse about this old guy in an old folks home that keeps reliving the war. And I don’t usually write story songs; I mean, I do, but I don’t have a tendency to write a lot of characters. So I wrote that verse and then I wrote the chorus, and I thought, that’s an interesting chorus — “it was just a dream.” Then I thought, Martin Luther King had a dream, so I wrote the next verse about how we shared this dream with Martin Luther King — which is also thematically repeated on “Spirit World.” And then I didn’t have a third verse, and I was playing this song for the guy who produced the album, and he said, “You have to put this song on the album.” But I said, “I just can’t think of another slant on that.” And I was in L.A., at a rehearsal, and I came out and I had 11 messages. I had talked to Mambo before I came out to L.A., we talked every other day because he was getting worse, it didn’t look good. So he was dying that day, and I’d gotten these messages saying, “You’ve got to call Mambo, he’s in the hospital, he’s dying today.” So I did. I called the hospital when I got in the car, and for once I was glad I had a cell phone. I called and he answered and we spoke. It was longer than briefly, but it was way too brief. I didn’t want to hang up. He was dying, he was surrounded by the guys in the Resentments, his mom and friends. Evidently that afternoon the hospital room just filled up with people, every hippie in South Austin. They played all the stuff he had worked on on the radio, and he was listening to it. I wanted to call him back but I didn’t want to, I’d said my peace and I didn’t want to waste his energy. So I talked to him, it was very emotional, I drove back to Santa Monica, I went down on the beach at sunset, and right as I got to the water’s edge, this fog bank hit, and I just fell apart. I went up to my apartment and wrote that verse. I went into the studio the next day — we’d recorded the song without the third verse — and said, “I’ve got probably one take in me.” We were all pretty broken up, because we’d gotten the message that he’d passed. And I realized that was the only way to end that song, was the aspect of this life being a dream for Mambo and for everybody. You should have seen the lyrics — they were just smeared with tears. It looked like a watercolor. But I’m real proud of that song. I get phone calls from people who say, “That’s the one that just killed me,” people who didn’t even know him. So evidently there’s a resonance there. Who knows … maybe I’m getting spirutal in my old age. You never can tell.

The flipside of that is “Acre of Snakes,” where the wise guy in you comes back out. I love the line “Is it crowded in here, or just you?”

[Laughs] I actually really like the one, “She wasn’t really smiling, only showing me her teeth.”

Is the crazy fan you’re singing about in “Acre of Snakes” a real person?

Oh yeah. Absolutely. There was a period when I was working with Bob Schneider — well also with my own band, and the Resentments, there seemed to be an awful lot of people — you should probably frame it with the word “people” — but there were some women that would come to these shows that were just off the graph, and one of them thought that I was communicating to her via my songs. [Laughs] She would give me tapes of songs that answered my songs. Then I later found out she had tried to kill somebody. Then there was another person up in Dallas who would show up and give me tapes, and you couldn’t understand what she was talking about. Ultimately, the bottom line was she wanted me to pick up a mobile phone and call Elton John for her, because she felt like she had to talk to him about something. And the best one was a person that kind of put me over the edge one night, I had just played with Bob, got off the stage, and a friend of mine was with some gal and she shook my hand and wouldn’t let go of it and said, “You don’t know what you just did for a friend of mine. You saved his life. He’s dead, but he was flying around you when you played.” And at that point I went, “Ok, I’m a freak magnet.” It just got kind of silly.

Well, what you’ve done now is all those people can come back to you and say, “See, you did write a song about me.”

Well, the thing of it is, in all honestly, they probably just hear that song and go “Boy, I wonder who that’s about,” because they don’t see this at all. In fact, one who I hadn’t seen in months and months was at the Resentments show last night, and talked all the way through that song. I sang it, and she and her friends talked all the way through it and never heard it.

So yeah, that song does have more of the wise guy kind of lyric, which is where I normally come from. But then there’s “Book of Dreams,” “Yo-Yo,” “Spirit World,” other songs that are a little bit more impressionistic, like poetry. Where you kind of write more for writers, you’re not trying to make a lot of sense, you’re not trying to make a point.

When you write, are you conscious of things you might have learned along the way from different people you’ve worked with? Where you might think, “Oh, that’s a Kristofferson trick,” or “I got that from Bonnie”?

Not really. There isn’t a trick to any of the writers that I grew up with. Delbert [McClinton] doesn’t use any tricks, Kristofferson doesn’t write with any tricks at all, Billy Joe Shaver doesn’t use any tricks, James McMurtry doesn’t use any tricks. That’s one of the reasons I really like the people that have influenced me; I was able to play for some of the greatest writers, and the reason I like these guys is they get the songs that touch you because they don’t use tricks. I think most of the stuff that you hear in Nashville — and not just Nashville, I’m not just Nashville bashing — but most of the stuff you hear on the radio, it makes you mad because it’s like some sort of stupid Hallmark greeting card with a chorus. It’s like “Have a Nice Day” with a bridge. And it just pisses me off. All it is is an exercise in cleverosity. It means nothing. No fucking meaning to it at all. So as a result it’s about as deep as your mirror — there’s nothing there, and it doesn’t mean anything to you two minutes after you hear it. It doesn’t stimulate a thought, it doesn’t stimulate you to think of anything beyond what you’re listening to. It’s filler. It’s all icing and no cake. And I hate that. I don’t mind clever, because I think clever’s good, you gotta be able to play off words. But if you don’t have nothing to say, shut up.

It’s a fine line between clever and stupid …

Yeah, but I’ll tell you what, it’s glaring. It may be a fine line between clever and stupid, but it’s glaring, because when someone says something that’s both, boy it just makes me want to get up and slap somebody. I’ve written with people in Nashville and L.A. that write a certain way and it works for them, they’re really good at it and occasionally they get a really good song out of it, but it’s a formulaic way of writing. And I don’t do it. Most of the guys I write with, all we do is sit around and talk about everything but writing, and after we stop laughing and poking fun at each other, we’ll start writing. I love writing with Al Anderson and all these guys, and they’re really great at what they do, and there’s something there — there’s an intellect there, and a lot of musicianship. I try to write with people that know the changes and know how music works.

You had a first class music education yourself, growing up in your father’s record store.

It certainly gave me a very high reference point, growing up in a record store with a jazz drummer father. That’s a very high bar. It certainly was an advantage that I can’t overstate. My father was a fine musician, he was from the Duke Ellington school of music where there’s just good or bad music, that’s it. And he didn’t put any pressure on us — he let us listen to whatever we wanted to listen to; in fact he listened to what we listened to as well. He wasn’t exclusive, he was inclusive. And likewise, I enjoy listening to all kinds of music. The record store in its own way was like a music school. You learn to listen to a lot of classical, a lot of jazz, a lot of pop. As a producer it really helped me out because by the time somebody asked me to produce them, not only had I had a lot experience recording on the other side of the glass as a sideman, but I was also able to draw on all the records that I had grown up listening to. I’m able to quote from various records that a lot of people had never heard, a lot of styles of music that are unusual. I can be like, “Hey you remember that bridge on such and such album from 1964? Check this out!” Or, “Listen to the way these guys played in 1934.” I mean, T Bone Burnett and I grew up together — we knew each other in junior high and high school, went to rival high schools — he and I used to go to my dad’s record store after hours to listen to stuff. I remember he and I were listening to “Man of Constant Sorrow” and “Oh Death” by Doc Boggs when we were in junior high school. These are songs that are all on the O Brother soundtrack. We were talking about a month ago and we were laughing about isn’t it great that we were able to hear all that stuff at the store, and turn each other on to all kinds of music that we both used. We were laughing about the fact that we were 14 or 15, sitting there playing “O Death” by Doc Boggs and going, “Man, that’s creepy – that’s cool.” Or “Man of Constant Sorrow” by the New Lost City Ramblers at the Newport Folk Festival. We were listening to all that stuff, and you don’t know where it’s going to turn up. Well, it turned up on the Album of the Year. He really knocked it out of the park I gotta say. I’m really proud of him.

So out of all the stuff you listened to, what was the first thing to really knock you out?

There were two things, well probably three things. Chuck Berry, and then the guitar solo on a rockabilly song called “Granddaddy’s Rockin” by Mac Curtis from Fort Worth Texas. And then a bunch of kids came into the record store when I was a little kid, they were practicing for a talent show, working on a folk song like the Kingston Trio. And I heard an acoustic guitar, and I was like, “Oh my god! Man, how cool is that?” All this sound coming out of this little box, with everybody crowding around and having a good time. I thought, “That’s it, right there.” So I was off to the races. I didn’t know how long the race was, though …

When you were in that race during the sideman days, were there moments when you could step back and really appreciate where you were, or were you too close to it?

No, not at all. I’ve never ever taken for granted the fact that I get to do what I love to do for a living. My dad was a passionate, great jazz drummer, and he raised a family, two sons and a wife. Had a day gig selling records all day and played music six nights a week. I was able to parlay that into just playing music for a living. And I’ve never, ever taken for granted the fact that I get to do what I love. I’ve probably taken a lot of things for granted in my life — we all do — but that’s not one of them. I’ve been grateful for that and thank the Lord, whatever you want to call it, thank my lucky stars, thank the Great Sprit every day that I get to do what I do for a living. Its like you are among the precious few of the precious few of the precious few that gets to do what they love for a living.

Last question: What’s the state of that long-talked about live album by the Resentments?

It’s been one of the most exasperating experiences, because we’ve had this album in the can for about a year and a half. And every time we try to get this thing together, something gets boondoggled. I don’t want to jinx it, but it looks like it might be coming to fruition very quickly and finally done in a couple of days, at which point I will cast it out upon the waters of production and manufacturing and see when it comes back. It’s going to be independent at first, but I think New West wants to pick it up, but at the same time every time you put out a record, you got to put all this machinery behind it to get some momentum behind it. And the big momentum behind the Resentments is the same club every Sunday. It’s kind of hard to ask someone to get all revved up about it. So we’re just going to put it out ourselves. It’ll be a fun record, and you’ll get to hear Mambo again.

No Comment