By Richard Skanse

“How did you find me?” asks a (somewhat) convincingly surprised-sounding Joe Ely by way of “hello.” “I’m in a small village in South America that doesn’t have telephones!”

Giving credit where credit is due, he almost had me — and not just because it still wouldn’t be entirely out of character for the old Panhandle Rambler to pop off to just about anywhere in the world on a wild hair. Out of the dozens if not scores of interviews I’ve had with Ely over the last 20 years, this is the first time he’s ever opened with a greeting other than a jovial “Hey, whatta-ya-know?” So, if not quite as jarring as hearing Willie Nelson kick off a concert with anything but “Whiskey River,” it’s just unexpected enough to elicit a split second lapse in reason. “Ha … wait, seriously?” (Note: Yes, I cringed hearing myself actually ask that in the moment, too.)

“Nah, I’m kidding,” he lets up, chuckling. “I’m home. I just got back from New Mexico. As Townes said, ‘New Mexico ain’t bad …'”

Ely was up in Santa Fe, hanging with fellow Lubbock-reared maverick Terry Allen again just a couple of weeks after their June 2 show together at Austin’s Hogg Auditorium. Even in a town famous for its live music scene, that particular evening served up quite the scheduling predicament for fans of quality Americana cursed with the inability to be three places at once; that’s because while Ely and Allen were holding court on the campus of UT, their pals Jimmie Dale Gilmore and Dave Alvin were celebrating the release of their Downey to Lubbock album at Antone’s, and Kelly Willis was playing her own album-release show at the Paramount. All three were solid choices, but those who opted for Ely and Allen — at least long enough to hear the first half before hightailing it downtown to catch some of the competition — were treated to something a bit more surprising than what could have been “just” a standard songswap between two legends. Joined by Terry’s wife, actress and writer Jo Harvey Allen, they devoted the entire first set to revisiting Chippy, their 1994 music and theater production inspired by the diaries of a West Texas prostitute. That they just dived right into it, sans any sort of expository intro save for Jo Harvey’s salacious opening monologue (a recitation from one of Chippy’s diary entries), was all part of the fun.

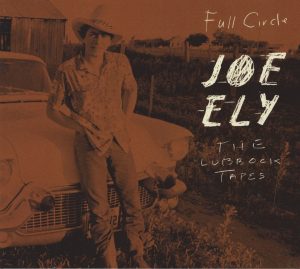

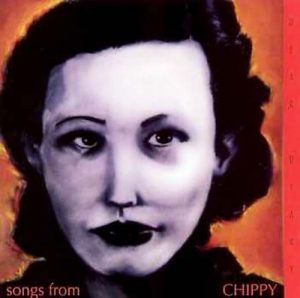

I’m eager to talk with Ely about that show, having long considered Chippy to be one of the most intriging projects he’s ever collaborated on; for proof, track down a copy of Songs from Chippy, featuring not just Ely and the Allens, but Butch Hancock, Robert Earl Keen, Wayne Hancock, and Jo Carol Pierce, all singing songs about a Lubbock whore on a CD somehow released by the Disney-owned Hollywood Records. But the main topic for today’s chat will of course be The Lubbock Tapes: Full Circle, a collection of previously unreleased demo recordings showcasing the earliest incarnation of the legendary Joe Ely Band in its ’70s prime. Over the past decade, Ely has issued a number of “Pearls from the Vault” titles on his own Rack ’Em Records label, ranging from 2007’s Happy Songs from Rattlesnake Gulch and Silver City (both comprised mainly of songs he’d written decades earlier but never gotten around to recording) to 2014’s B484, his original, homemade version of 1984’s Hi Res. But unlike most of those releases (not to mention many more still in the pipeline), The Lubbock Tapes were not culled from Ely’s personal treasure trove of shelved recordings and unfinished passion projects; in fact, he swears he didn’t even know the tapes still existed until his old friend, former pedal steel player and apparent fellow hoarder Lloyd Maines, found them buried in a box at his own place.

“The Lubbock Tapes: Full Circle” was released on Ely’s Rack ‘Em Records label in August.

Ely was still in the early stages of sorting through and digitizing the lost and found recordings the last time I interviewed him, a week before his 70th birthday back in February 2017. Naturally, he already had plans on releasing some of them, having gone so far as commisioning Nashville producer Ray Kennedy’s services for repair and restoration work on the 40-plus year-old tapes. But everytime Ely played me some of the tracks off his computer that day, he almost looked like he was hearing them all for the very first time himself — especially the 1974 demo of “Because of the Wind,” recorded before Jesse “Guitar” Taylor joined the band but with Maines’ signature keening steel sound already fully formed. “When I first heard that,” Ely marvelled, “it kind of brought tears to my eyes. Because that whole band … it had such a great spirit to it, you know?”

And to think they were just getting warmed up. By the time MCA Records released Ely’s self-titled debut in 1977, the band, locked and loaded with the inimitable Taylor then in place as the proverbial thunder to Maines’ lightning, was firing on all cylinders. Of course the evidence was always there on the rest of the “official” albums that the original Joe Ely Band recorded together: 1978’s Honky Tonk Masquerade, 1980’s Down on the Drag, and 1981’s Musta Notta Gotta Lotta, not to mention 1980’s absolutely essential Live Shots. But the 15 demos from ’74 and ’78 featured on The Lubbock Tapes go a long way towards adding even more luster to that legacy by proving just how special that band truly was from the get-go, even in the raw. Or when required, by honky-tonk law, to serve up a good schottische.

So Joe, it’s good to visit with to you again — and to get to hear these demos again. But before we get to The Lubbock Tapes, I wanted to ask you a little bit about that show you did with Terry Allen this summer in Austin. One of the things that really surprised me about that night was just how little the two of you talked onstage. Given the way song-swaps like that usually go, I went in figuring there’d be as much joking and story telling between the two of you as there’d be actual songs. But I don’t think the two of you talked for more than two minues the whole show! Was that the plan going into it?

[Laughs] No. We just, you know … I guess there’s been a couple of different times now where we’ve done kind of a sketch piece of that play we did back in the 1990s called Chippy. And since we were all going to be in town at the same time for this one, we dug through our old notes and just formed a little story kind of based around that play, with Jo Harvey reading parts from the diary as Chippy herself. It just opened up an opportunity for us to play a different set of songs, and let the songs tell the story instead of us explaining it.

I thought it was funny how even Jo Harvey didn’t really even mention Chippy by name until the very end of that set. I never saw the full play but I’ve always loved the “soundtrack” album, so I caught on pretty quick — but there had to have been a few eyebrows raised in the audience when one of the first things Jo Harvey said at the start of the show was, “My only regret was not sleeping with 6,000 men …”

[Laughs] Yeah, it’s funny … and we we kind of figured that would be a harsh way to open! Because when we’ve done that Chippy set in the past, we would talk about how the play came about — like when we did it in Dallas a few months ago, we actually told the story first. But it kind of felt like you were almost making an excuse, you know, for what was coming up — instead of just letting the songs themselves tell the story in a more abstract way, so that the audience could sit there and try to undo what it was all about instead of being told first. So we switched it aound this time, just as an experiment of a different way to present it. But we never really have a set script intact; we leave it open to let other things come in.

I know Terry and Jo Harvey Allen wrote the play together, and you and the rest of the original cast all contributed original songs. But where did those Chippy diaries come from in the first place?

1994’s “Songs from Chippy” (Hollywood Records)

There was a teacher, in Wichita Falls, I think, who somehow came across the diary — or she knew Chippy and Chippy gave her the diary at the end of her life. And she kept them around for years. And then Joe Sears and Jaston Williams were playing Greater Tuna somewhere around Wichita Falls, and the teacher got to talking with them and asked Joe Sears to see if he could maybe do anything with them. He told her he’d look at them, or pass them on to someone and would stay in touch. And so we all kind of got to go through pieces of the diaries, and it turned out that we just kind of took over the project. I started working on a record and writing songs for the play, and we started doing just little sketches of it in different places until gradually it developed into a complete little story. The Philadelphia American Theater Company decided to bring it to Philadelphia, so we took it there and played it for 11 days, and then we took it to New York and played it for five days at the Lincoln Center. And that original cast had Robert Earl Keen, Wayne “the Train” Hancock, Butch, and Jo Carol — just a whole bunch of people, so it would be difficult to reconstruct the whole thing, but we were wondering if we could strip it down and do it more as a story instead of a play. So that’s how it kind of came about, as near as I can tell — it made a few sharp turns left and right, but it’s fun to do because it’s a different way of presenting an era.

Were there many more songs, old or new at the time, in the original play than the ones that made Songs from Chippy album? During the stripped down Chippy set at Hogg Auditorium, Terry played his “Gimme a Ride to Heaven” and you sang “Because of the Wind,” both of which fit right into the narrative.

There were some things like that, yeah. But I also wrote another six or eight songs for it myself, and Butch and Terry wrote some, too. I think all together there were about 25 songs. “Cold Black Hammer” was one that I wrote for Chippy that I’ve since recorded again, for Panhandle Rambler. So things come around, and it’s fun to kind of dust them off. And that’s in the literal sense, because when we did the play in Philadelphia and New York, it was in our contract that the whole stage be covered with six inches of dirt. So every time there’d be a big dance scene, the whole auditorium would fill up with dust. The theater people hated us! [Laughs]

Well, speaking of dusting things off, literally or not — that’s as good a transition as any into talking about The Lubbock Tapes. I remember when you played me a few of these demos a year and a half ago, you said you hoped to eventually get around to releasing them. But knowing that you always have so many different irons in the fire, I was honestly kind of surprised at how quickly you followed through on that.

Yeah. Because, you know, the tracks were already there. They were tracks that Lloyd had given me a couple of years ago; he’d given me a box of tapes and said “Dig through here, it’s some old stuff …” And I guess it was kind of like when we got the “Odessa Taples” that the Flatlanders had made and forgotten about, where I didn’t really expect much out of it. Because back in those days, I didn’t really even think about recording, and when I did I never thought about going back and lisening to anything after I’d recorded it. I pretty much dropped everything as I was leaving Lubbock, and after I got that old band together with Lloyd and Jesse and Ponty and all those guys; I moved to Austin, then took off across the ocean and kinda just left everything behind. So I had forgotten some of those really early recordings, but sure enough, Lloyd had them the whole time. And he didn’t even know … he had them in a box of his own tapes, and didn’t really know what was on them himself. So I was really surprised to find that they were done in a studio and really produced well.

Just because of the fact that you already have so much other unreleased material to sort through in your own archives, anytime Lloyd or anyone else brings you something like that, does it take you awhile to get around to actually listening to it?

No, I dig into them immediately. I’ve got a whole stack of them … I can’t release three or four live tapes in a row, you know, so I think I’m going to kind of make a little online store where you can go in and look at things without it being an actual “record release.” Because there are other things that I want to put out — like this great live tape from 1977 or ’79 from Minneapolis, at a place called the Cabooze club. It’s just a smoking set from that early band. So I’ll probably do that in the next few years. But in the meantime I’m working on several collections of these songs.

Have you looked at Neil Young’s massive archive site yet?

I have looked at that, yeah. That’s exactly what I was kind of looking at as a way to, you know, have fans be able to see all of the archives without having to release them as a project. So that’s definitely a model that I see as a really good way to go about it.

Well, as one of those fans — I would hope the option would still be here to buy and download things off of such a site. Streaming is fine, but I’m still old-school enough to want to buy and “own” stuff that I really like.

Oh yeah, me too!

So these tapes Lloyd gave you, they were from two different sessions?

Two different sessions, right. The first was from ’74; I think I put the earliest version of the band together in ’73 and we started recording in ’74. And the next group of tapes was from ’77, ’78. The band had changed by then. Jesse had become the full time guitar player. The first group of songs, there was a guy named Rick Hulett. And then by the second set, Jesse came in, Ponty Bone came in, and a different drummer, Steve Keaton. Same bass player, though (Gregg Wright).

What ever happened to Rick?

Rick decided to go to school in Portland, Oregon. Marine technology or something. We were making $10 a night, so it was not very profitable playing in a honky-tonk band. Later on we built an audience, but at first it was difficult. But that was Rick Hulett playing on all the first tapes on this collection, and Jesse came in after that, which would have been around 1975 or ’76. He was working with a band called Crackerjack, I think with Tommy Shannon. They were a really great blues band band, based out of Houston I think. I saw Jesse playing with them and thought, man! So, I talked to him after that show and asked if he’d think about joining my band. And then not long after that, the band Crackerjack kinda fell apart and Jesse came back to Lubbock, and I ran into him again.

Jesse was very much part of the band by the time you recorded your first album. But even though he didn’t join the group until after you made that first batch of demos, you had actually known him for a while before 1974, hadn’t you? Even before you saw him in Crackerjack?

Oh yeah. It’s funny — the first time I met him was in Venice, California, in about … ’69, maybe. He was out there with some of his Lubbock friends. I had come out there on my own, and I was walking along the boardwalk, and I heard these guys in front of me, talking in strong West Texas accents. I went up to them and said, “Where you guys from? You sound like you’re from West Texas.” They said, “Yep, we’re form Lubbock.” And we started talking about people we knew. So that was the first time I met Jesse. And then in the early ’70s, me and Butch and Jimmie used to get together with Pony Bone, and go out and play out at Ponty’s house out in Slaton. And Jesse started coming out there sometimes and playing with us acoustically. So, after the Flatlanders went off all different ways, I had actually thought about Jesse quite a few times, because he was just a blistering blues player. And when he finally came in and me and him and Lloyd sat down with the songs and started working out arrangements, he just added a real fire to what we were doing.

Although the tracks on The Lubbock Tapes come from two different sessions three or four years apart, with two slightly different lineups, the actual sequencing on the album mixes them all up. The songs aren’t separated by session date.

No, they’re not. Because I didn’t want it to be … you know, if you order all the songs by date, then it becomes just an “historical” record or something that’s …

Too academic?

Yeah. Instead of that, I really wanted it to capture the feeling of that time when we first started playing together. I had put this group of great bar musicians together, but also guys from the honky-tonks — like Lloyd, whose whole family was a part of that Lubbock honky-tonk scene. And in the begining, we were part of that scene, too. Before we started playing all over the United States and Europe, which was a big change, we were basically a pure dancehall band, because to play those Lubbock honky-tonks, you always had to be able to play a schottische and a waltz, a two-step, all that kind of stuff. So that’s what’s you hear on [The Lubbock Tapes]: that pure band before we ran out into the world, still very much West Texas inspired.

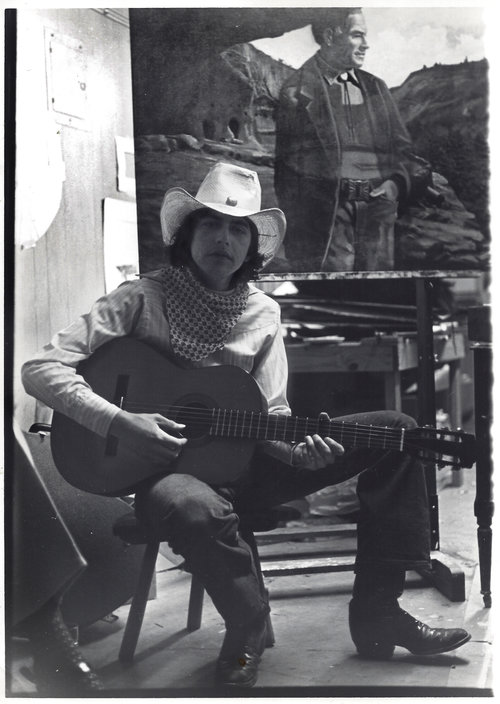

Joe Ely back in 1974. (Photo by Jim Eppler)

The only song on The Lubbock Tapes that I was unfamiliar with was “Joe’s Cryin’ Schottische.” To be honest, I didn’t even know what a schottische was.

It’s an old German dance where everybody kind of hooks hands and goes in a big circle, does a couple of kicks. We always had to play one of those, so I just did my own.

When you came across that song on the tapes, did you even remember it?

I did not remember recording that. Nor did I remember us recording “Windmills and Watertanks.” In fact there’s several on there that I did not remember recording at all.

How well do you even remember that first recording session?

I really don’t! But that first bunch of tapes, I think there were eight songs on it. We did them at Don Caldwell’s studio, which was kind of the center of the Lubbock music scene, and we must have recorded them all in one day, because it was so expensive. But we were really well rehearsed. I think what I did was, after I got out of the Ringling Brothers Circus, I spent about five or six months finishing up all these songs that I’d started and really planning out and working on our selist. But as far as recording them went, we just stopped in, turned on the machines, played through all the songs and left at sundown. It was much the same as the “Odessa Tapes” with the Flatlanders; those were all done in one day, too, only in a different studio.

And that was the tape that eventually landed you your record deal with MCA, after Jerry Jeff Walker passed it along, right? How did he come to hear it?

Because of Bob Livingston; he was playing with him. I knew Bob because he had a little club that was in an alley across from Texas Tech, and I used to go down there and play sometimes. I don’t think they even had a mic down there; it was just a little room in a basement that held about 20 people. Anyway, that’s where I got to know Bob Livingston, and that was about the time that I played him that tape, and he somehow got that tape to Jerry Jeff and to MCA. That tape was also how Jerry Jeff heard that song of Butch’s “Standin’ at the Big Hotel,” which he ended up recording on his own album [1976’s It’s a Good Night for Singin’].

That must have been like getting the king’s blessing at that particular point in the ’70s.

Oh yeah, definitely. Jerry Jeff was …

Riding high?

Riding high, yeah! In many different forms! [Laughs]

You mentioned another Butch Hancock song from the 1974 session that’s on The Lubbock Tapes: “Windmills and Watertanks,” which the Flatlanders first recorded in 1972 as “You’ve Never Seen Me Cry.” Why the name change?

Because that’s what I always called it! I think “You’ve Never Seen Me Cry” is the real name of it, but I’ve just always called it “Windmills and Watertanks.”

Six of the songs on The Lubbock Tapes were written by Butch. From the very beginning with the Flatlanders and all through your solo careers, you and Jimmie both have really gone back to that well a lot over the years. Can you talk a little about what it was about Butch’s songwriting that’s always stood out for you? All three of you have talked in the past about how influential Townes Van Zandt was to the Flatlanders; but even before you heard Townes for the first time, had Butch already set the bar for you?

He had. Because Butch’s songs, they were like songs inside of songs. He had little trick catchphrases that would make it a completely different meaning with just the change two words. He’s just a master at that. And I guess I’ve always felt like that about his songs, ever since I first met him. He has not stopped making completely great pieces of work.

Do you have a hands-down favorite Butch Hancock song?

Oh, I guess just for sheer beauty and mystery and all, “You’re Just a Wave, You’re Not the Water.” That song just slays me every time I hear it. Chops me in half.

Jimmie’s recorded that one a couple of times, but I don’t think you have, have you?

I have, but I’ve never released it. I’ve got a couple of hundred songs that I’ve recorded and still hope to release some day. But that one … it’s almost like, when I produced that record that Jimmie first sang it on (1988’s Fair & Square), Jimmie sang it so well, I guess that’s why I never released my own, because I didn’t think I could top what Jimmie did with it.

Another Butch song on The Lubbock Tapes is “Down the Drag,” which of course was also the title track to your third album. That whole album has always been one of my very favorites of yours, but I seem to remember hearing you and Lloyd both talking about how neither of you were particularly crazy about it. Why not?

Well, I like the record, I just didn’t like the mix. The mix seemed real flat. And I think that happened because … I don’t know, I usually follow records all the way through, and I didn’t with that one. We recorded it with Bob Johnston up in Seattle, and it was a little, oh, kind of depressing there. We were there during winter time, and it was 43 degrees and raining every day. So after we finished it, instead of going down to San Francisco to be with the mixing engineer, I went back to Lubbock, and I think the mixing engineer just had a different impression of it than Bob Johnston did.

So you got along ok with Bob?

Oh yeah, I got along great with him. He was great fun to be around. He had great stories. But he basically just turned the band loose, saying, “Here, y’all know these songs,” and didn’t really produce so much as just kind of let us go. And I kind of feel at that time, we could have used a little more of a production hand, because we were in strange town in kind of depressing weather … we kind of needed maybe a little more ambiance or something on some of the record. But The Lubbock Tapes shows a few of those same songs that we recorded on the Down on the Drag record, so you can kind of get a feeling of where we were trying to come from. And I do think they actually feel better on The Lubbock Tapes.

I think one of my favorite songs on both Down on the Drag and The Lubbock Tapes is Ed Vizard’s “BBQ & Foam.” That’s such a quintessenial Joe Ely sounding song to me, it’s really hard to believe it wasn’t written by you or Butch.

Yeah. Somehow I think Jimmie had met Ed in Austin in the ’60s, and that song of his just always stuck with us. From the very minute that we first heard it, something about it just felt right, you know? It felt like a Flatlanders song, and it felt like a song for each of our own bands, individually.

This might seem a little left field, but as long as we’re talking about old Lubbock tapes … Lloyd Maines and Terri Hendrix were on KNBT earlier this summer, doing this “Turntables” show where they have guest DJs playing their favorite songs. And Lloyd dug up this really cool recording of Stubb [aka C.B. Stubblefield of “Stubb’s BBQ” fame] singing “Summertime,” I think with most if not all of your band backing him. Do you remember anyhing about how that came about?

Hah! Yeah. Stubb used to have this jam every Sunday that Jesse had helped him get started. All the musicians in town would gather at Stubb’s on Sunday night and have a jam session that lasted six or eight hours. And Stubb would always get up and sing two or three songs himself. He had “St. James’ Infirmary,” “I’ve been down one time, I’ve been down two times …” (“Drowning in the Sea of Love”), and “Summertime.” And he’d always start that song off with a little dialogue: “Yes, ladies and gentlemen — there’s one thing that we all know for sure …” And everybody would sit back and listen: “Everybody’s got a mama!” (Laughs) And then he’d break into “Summertime.”

I’d love to hear that again sometime.

I think I have a single of it some place. I’ll see if I can find it.

With all of the cool stuff in your archives to go through and hopefully get out, not to mention all these other old tapes that seem to keep turning up … how do you ever manage to still work on new songs and projects? How strong does the urge to make a new record have to be for you to put everything else on pause?

Well, I’m working on two or three like that. It’s just a process, you know? It kind of depends on where I am at the time. But boy, I don’t know, that’s a good question. I don’t know if I’m the one to answer that.

So what do you think will be next? Something old or something new?

Something new. Or something … there’s something almost finished that could come in next. There’s a sequel to Panhandle Rambler that is almost finished. And there’s tributes to different songwriters. I have a tribute to Guy Clark, and to Townes, and Butch. A lot of people I’ve worked with. It’s just, when the wind blows one of them a little harder and pushes it out front, that’s the one that I work on …

Oh, man — I just looked out in my back yard, and there’s a wild turkey with three baby turkeys.

Do you get those often?

Yeah, they’ve been coming around quite a bit over the last three or four years, actually. They kind of make this daily stop on their quest for corn.

Are baby turkeys cute, or do they still look like turkeys?

No, they look like little … they’re about a foot tall, and kind of pop up and down, like they’re coming out of a toaster. (Laughs) They just follow their mother, and jump up and down, like frogs or something.

Ha! Well, speaking of distractions — and turkeys! — before I let you go, do you have any thoughts on the upcoming midterm elections? Or more specificically, do you think there’s a legiimate chance for a Texas blue wave?

Well, we’re hoping so! I cannot decipher American politics these days. I just don’t understand. It’s so totally and completely different from the politics in the ’60s and ’70s, even the ’80s. I’m just hoping for a big change. That’s all I can say.

Taking encouragement where you can get it, when you sang the Flatlanders’ “Borderless Love” during the second set of that Austin show with Terry Allen, the audience really responded in a positive way to the “there’s no need for a wall” line. I also thought it was pretty inspired the way you and Terry put together a running theme there, with Woody Guthrie’s “Deportee,” “Borderless Love,” and his “Big Ol’ White Boys” all working off of each other.

Yeah. That song (“Borderless Love”) has kind of re-entered my repertoire. But I don’t know … crazy times we’re living in. And it’s hard to, you know, find songs and do shows like that in the state of modern day America.

The enthusiastic response to “Borderless Love” in a progressive-minded town like Austin is one thing. But have you ever played that song in other parts of Texas or the country, either solo or with the Flatlanders, and gotten the opposite reaction?

Oh, yeah! In fact I had a guy grab me around the throat and try to drag me off the stage as soon as I played that song once. He actually got physical. It was in Philadelphia or Pittsburg.

For real? That’s pretty unbelievable.

Yeah. He just said, “Why do you have to politiciize everything?” I said, “That’s the way it is, man. That’s the way I feel.”

But he actually grabbed you off stage, though?

Well, right from the wing of the stage as I was walking off. Don Boles [Ely’s road mangager] was there and he got in between us, and the bouncers from the venue saw something was going on and they came down and got the guy off my neck. But yeah! You’d think those cities would be more wide open to, you know … But, they’re close to the border of Canada. So maybe he thought …

Well, Canada’s one of our worst enemies now, apparently. So you can understand the tension.

[Laughs] It’s a wacky world. I just kind of look at it day to day, and wonder how it got here, and wonder how we’re all going to get back. But, that’s a whole ‘nother set of songs!

Thanks ojnik

[…] He told me the same story! I didn’t know you were at that show with him, though. […]