Lubbock’s most philosophical musical export ponders the mysteries of artistic motivation, songwriting and the joy of making “Heirloom Music” just for the fun of it.

By Holly Gleason

(LSM May/June 2011/vol. 4 – Issue 3)

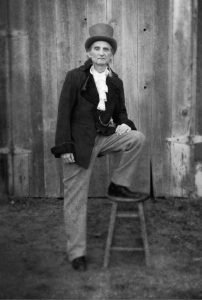

Over the years, Panhandle-born ’n’ raised singer-songwriter Jimmie Dale Gilmore has been many things to many people: a cosmic poet; folkie with a voice that’s all silver ’n’ lonesome; a member of Lubbock’s casual semi-supergroup, the Flatlanders (featuring good friends and fellow critically acclaimed artists Joe Ely and Butch Hancock); a rural blues singer; a crooner who evokes tube radios; and yes, for fans of The Big Lebowski, “Smokey.”

The vast net of Gilmore’s musical wanderlust can be explained as much by the company he kept as the wide-open sky that covered much of Texas in the ’50s. Always curious, deeply rooted in Eastern and Indian philosophy, Gilmore has long been an open portal to everything from quantum codes and advanced physics to Hollywood dynamics, Bob Dylan, good friends and the pleasure in every moment.

Having last explored the depths of the country music he shared with his father, on 2005’s Come On Back, Gilmore is now ready to release an album that goes even further back: Heirloom Music, which he recorded with a ragtag troupe of everyman players from the Bay Area called the Wronglers. A spur-of-the-moment notion that grew into an actual album, the joy of the performance on the new collection is palpable: It is about the thrill of making music together, the triumph of holding up near-forgotten songs from another era and the opportunity to remember how great handmade music can be.

Like so much of his reality, Gilmore’s decision to record with the Wronglers comes from an organic place. Wrongler Warren Hellman — by day, a big deal, low-ego private equity investor — is also the man behind the Golden Gate Park’s storied Hardly Strictly Bluegrass Festival, where Gilmore is a mainstay. Gilmore and Hellman developed a friendship that was more than backstage reveries, the pleasantries of the once-or-twice a year variety that holds many relationships between civilians and performers together. Heirloom Music, the eventual bloom of their friendship, is a sparkling celebration of myriad styles that predate much of the country music that Gilmore — and even his country guitar-playing father — was raised on. Drawing on often-overlooked aspects of the man with the singing voice like a loon’s roots, this is a ragtag collection, ranging from “Deep Ellum Blues” to the Carter Family’s “Tonight I’m Dreaming of My Blue Eyes” to the hobo’s version of “The Big Rock Candy Mountain.”

Still, to hear the strummed mandolin and the elegiac beat of “In the Pines” rendered with equal amounts dignity and solemnity, it’s obvious that for all the fun these folks are having, the music is what matters to them. For Gilmore, now entering his 16th year as an adjunct professor at the Omega Institute in upstate New York, that is where the road begins and ends: loving the music and making it matter.

Is it a strange thing, for you to embark upon a project that’s sort of bluegrass?

Not necessarily. Though Joe Ely told me he’d wanted me to do a bluegrass record for 40 years, ’cause he wanted to hear it. It’s always been a piece of who I am.

But it’s not strictly bluegrass, is it?

No, this really isn’t a “bluegrass” record, because bluegrass is so tightly defined. There’s a definite sense of song structure, instrumentation, approach. You realize that in the last 500 years, there’s only one genre of music credited to a single artist, and that’s Bill Monroe with bluegrass. His sensibility was so strong, he literally created the genre, and it is pretty strict.

The music here is almost old-timey…

A lot of this music is, yes, pre-bluegrass. It’s older. In some cases, much older. And old-timey is such a braod category: the Carter Family, Charley Poole, the Bristol Sessons recordings. But the trouble is the term “old-timey” has acquired a sort of pejorative feeling, a kitschyness. And this music isn’t kitschy. It’s simplistic in some ways, but that doesn’t make it quaint. And that’s why we named the record Heirloom Music. It’s related to bluegrass and old-timey, but it’s different. There’s country blues in here a little bit, some folk …

Do you think this is your root essence?

Not necessarily. First, I don’t think in those terms. But factually, it’s certainly a piece of it. But it doesn’t cover other aspects of who I am: the folk blues from when I was first learning to play, the rock and soul stuff I got into later. It’s all in there. From very early on, I think what impress me more had to do with emotion than style. I was deeply in love with Nat King Cole and Eddy Arnold, then Hank Williams and Lefty Frizzell, ’cause of my Dad. It was Little Richard screaming or Elvis singing a ballad the way he did … It all hit me! Later, it was Ray Charles, who kind of blurred lines, too. Whether it was his country stuff or his R&B stuff and soul stuff, it just got inside me. And that’s always been the thing: Whatever hits an emotional chord in me, that would be my music. It wouldn’t be accurate to say I was a big country fan, or a blues fan, or whatever, because I was never about the label.

But this music is most certainly specialized.

Absolutely. And I think it’s what brought Warren and I together.

The music?

Exactly, The music. For me the simple fact that I have a love for this music … and I’ve played with so many great musicians, but they don’t really share my love of this sort of music. It was always more rock and blues for them. [Like] Jesse Taylor, as fantastic a musician as there is, was more blues and not interested in this kind of thing at all. So, this was something I got away from … though when I did NPR’s Fresh Air, Terry Gross went back to After Awhile and pulled that version of “Tonight I Think I’m Gonna Go Downtown,” and was surprised by how similar it was — the performance on this record and After Awhile. But that’s the thing … you know, this music has always been part of everything I’ve done, it’s just not something people notice. It’s something that’s just part of it, but maybe didn’t stand out for what it was. Something maybe they feel, but not necessarily something they’re gonna define. On that subliminal level, it works. You know it’s there, but no one’s gonna say, “There it is!”

Can you explain?

To me, this lies more on the song’s content and the vocal. “Columbus Stockade Blues” was the first thing my dad taught me the chords to. And Warren’s very much the same way! He has the most amazing repertoire: vaudeville things, old folk songs, things from other countries. And he also has this amazing openness and innocence that way.

So you two became friends …

Yes, this all came from my accidental friendship with Warren. I went out to Hardly Strictly close to 10 years ago, and we hit it off. Dawn Holliday, who runs Slims and the Great American Music Hall [and the Hardly Strictly Bluegrass Festival, all in San Francisco] knew that based on the kind of music we both liked — and how few people really do like it — we should be friends. He lives in this world of ultra-high-finance, but his love of music is so pure and genuine. He gives the gift of that festival to the people of San Francisco just for the joy of it. And he’s always doing things like that.

And one of those things led to — inadvertently —

Heirloom Music.

Four years ago, we went out to play at a fundraiser for this radio station in Bolinas. Warren and Heidi Claire, the fiddle player in the band, played, too. Then Robbie [Gjersoe] and I were on. Somehow I coaxed Warren to get back up onstage and play with us. And it was so much fun. You don’t get to play with people who’re having that much fun very often. It just stuck with me. And then they came to town for South by Southwest and the Old Settlers reunion last year. Generally when we’re in the same area, we try to get together, try to have a meal or something. So it was Warren, the band, and Dawn Holliday, who’s responsible for us knowing each other. We were all just sitting around the table after dinner, talking about whatever was going on. It was very friendly, end-of-the-day stuff. And I said, “I have an idea, and I just wanna see if it’s a stupid idea ’cause you never know until you put it out there …” Everyone asked me what I was thinking, and I said, “Well, I don’t know about you guys, but what would you think about making a record with me? Just doing a record that’s kind of this music we all love, and seeing what we come up with. It might be crazy, but …” They were al like “WOW!” and “Wonderful!” I was shocked that everyone seemed to think it was a particularly good idea, because it was so left field.

But it was also kind of organic.

Yes, yes … I was almost embarrassed to bring up the idea. It seemed so off the wall. But like the Flatlanders, my deal with them is based on friendship versus you know, hired guns. That’s funny, sorta … hired guns of old-timey music? [laughs] But this was spontaneous, just the way Joe and Butch and I decided to do the Flatlanders. They both arose spontaneously from our shared love of certain kinds of music and the friendship that we all have between us. For me, it’s how it works …

No calculating the right move, just …

What feels right.

There are some other similarities to the Flatlanders, though, beyond just the friendship. Maybe not obvious, but they’re there.

Oh, yes. You know, the Flatlanders did some of this kind of music in the beginning; then later we got into electric stuff. The Flatlanders developed into something with a pretty intense rhythm section, but we started with this sort of music. This record (Heirloom Music) has no drums on it; neither did the first Flatlanders [originally released only on 8-track, now available as More A Legend Than A Band]. And ironically, this album is all acoustic, except for the bass, and the Flatlanders was all acoustic.

And would it be okay to have you explain a little more why this isn’t bluegrass? Just so people can tell the difference.

Let’s see … where do you start? Bluegrass is truly refined and polished. Someone like Ricky Skaggs, to me, is to the point where it’s not even musical, but more acrobatic!

That how-many-notes-can-you-play-in-a-second idea, right?

Yes, and they’re the right notes. And that’s very amazing and fun, but — for me — it doesn’t have the same charm as song-driven play. There are those songs that are blazing fast and they do have an emotional thing to them, but that’s not the reason for them. It’s still about the playing; and it’s so intense and structured, it’s almost mathematical. It’s amazing. But with this music we’re doing, the whole thing is the songs; it isn’t in the playing.

Yet, there’s a gray area, sort of.

You look at Bill Monroe, it’s generally mandolin-driven. Later there was Earl Scruggs, and the Scruggs-style banjo – but what we’re doing is the frailing style, which is more old-style banjo that was brought back during the folk revival. And again, both have a lot of emotion in the songs, but what we’re doing, the impact lies more in the song’s content and the vocal.

Well, your voice is certainly distinctive and Warren’s is, too. It has this very broken-in feeling to it … and a realness.

I think that’s true. You can really tell … When he brought in “Big Rock Candy Mountain,” a lot of people think of it as a children’s song, but it’s not. It’s a hobo song! I know I loved it when I was a kid and everything, but Warren wanted to do the real hobo version. He has that sense where he can get you to understand this is a hobo song and that the Big Rock Candy Mountain is Shangri La for bums who were bummin’ around, jumping train cars and such. And that’s how Warren sees the world and music: transformatively.

You played at South by Southwest this year. Will we be seeing more of you and the Wronglers?

They’ve done gigs around the Bay Area, special events, but we’re going to tour this summer. Get on the bus and do some shows and festivals. We’re not a young band, so we won’t be vanning around, but I think there’s going to be a real live tour — go to some cities that make sense, play shows. I’m looking forward to it!

Apart from dates with the Wronglers, do you have any other shows?

Interspersed with all this, I’m doing a lot of stuff with Butch and Joe, too. Playing where I’m wanted, because you want people to hear the music if they want it.

And recording?

Yes, that, too. I’m going to carve out a chunk of time to do my own record. Just make it about the songs. You know, that really is it for me. Right now, it’s an as-yet totally unknown and unspecified sort of style. Nothing’s been pinned down. The place we made the last Flatlanders record is out by Dripping Springs. Lloyd Maines produced and he took us out to this place called the Zone. It’s my pipedream to get back out there. Just go out there and let the songs dictate. I’ll be my own A&R person.

That seems like a good thing to do.

There’s that Ezra Pound quote: “The poem fails when it strays too far from the song, and the song fails when it strays too far from the dance.” That’s the thing about music. It’s unspoken, when it’s working, what it can do. It’s a tool for letting people get closer to each other. It’s why churches use music. It’s why people use music to commune with each other, to bring people together. And over the years, I’ve learned many musicians don’t want to talk about this stuff, because they’re afraid it will ruin it on some level. Most people, though, aren’t consciously aware of it. But really it’s a communion of sorts, or an organism that unites everybody. It’s not conscious, but that’s what gives it its power. It’s what makes people want to listen — and being open, I think, is how you find it. And I learned that in my songwriting class.

Yes, the Omega Institute! Are you going back again this year?

Yeah, it’s the one constant I’ve had over the last few years — and this is going to be my 16th year there! It’s become something so important and meaningful and clarifying to me, about all of it: life, creativity, human dynamics. And it’s funny because the first year, the idea that the teacher is the one who learns the most is such a cliché, but it also happens to be almost universally true! It really is.

Was that a strange thing to undertake? Teaching?

Consciously, without realizing the name is the Omega Institute for Holistic Studies — it kind of explains why they asked me. Somebody there knew enough about me, about my music, to know that I’d fit, because the music and philosophy aspects really come together. That’s a big part of it. The process really came together for me when I came to the realization that there’s lots of ways to look at songwriting and playing music that reflect our most intuitive nature. Teaching’s made me really become conscious enough to be able to articulate what I do. I teach methods of thinking about it; not so much mechanics, but more an approach that lets people experiment in the way I do. I don’t give lectures [laughs], but I do talk a lot. But it’s more how do we look at this process or whatever we’re writing about. It becomes a bit more about motivation than the next chord.

Do you care about structure?

In some basic respects. I prefer good rhymes to approximate rhymes. I prefer people playing together to be in tune and on the beat together. So there are tendencies where I am a traditionalist, but my favorite blues stuff is all out of tune and out of rhythm. What I will always go back to is, the thing for me is the emotional response. Whether it’s my song or someone else’s, that’s what I want to get. And I am open — you have to be open to what’s out there! I’d also say, “If you know how to do it properly, then you can do it deliberately improperly!”

And you learned all this in school? I mean, Omega school.

When you’re doing a songwriting class and you start analyzing, suddenly you’re in all this backstage psychology. You’re seeing the seamy underside of where the songs come from, which in truth is as beautiful as the topside, though most musicians don’t want to consider it. But if you can see the underside and still have a love for it, to see the possibilities and consider it dispassionately and objectively — if you can still return to it with the passion to do it, you’re going to start doing it at a whole other level! That is where the real beauty comes from. I don’t teach in any traditional way. I’m there asking a lot of questions, trying to open up the songs or what they wish to say. Big questions are, “What’s the right motivation?” But knowing what your focus is is also critical, and too many people don’t think about that. Its genesis came from this llama Janet [Gilmore’s wife] studied with one year. The idea that the reason for everything is the motivation — we thought he was this ginormous genius thinker, but really, it was Tibetan Buddhism 101. [Laughs] Still, back in ’97, it had a profound effect on both of us. It’s the reason meditating is so important, too — so you can known your motivations, because when you know what they are, you can’t be driven by them unconsciously. Once it is known, you can deal with them or be aware of them, but you realize when they’re working. In songwriting, that’s so important.

Which brings us back to Heirloom Music, doesn’t it?

Kind of, because to record these songs in an almost primeval way, it was the motivation that mattered. And the band didn’t necessarily know these songs, but they were in the style they played in anyway. We did a week of pretty intense rehearsals. Everyone does other things, but they all come together because they love playing. It sounds so unlikely, but that’s actually what makes it work. It really is that thing. I’ve wondered all these years: what is it? How can playing a song or listening to a song cause you to have these deep rich emotions? And they do. Getting to the age I am now, it’s amazing to me how songs can still hit like I was a teenager. So much is watered down by pure ignorant profit motive in conflict with artistic motive. You can’t really have both … but artistic motive can work beyond that if you’re lucky. But you can’t worry about that. That’s the beauty of this record: we didn’t. We came. We played. We had fun. We enjoyed each other and making music. Now there’s this record, and you can hear all that. To me, that’s the reason to do this. If you can make that happen, then you’ve done something that may move people — and that’s worth remembering.

No Comment