By Kelly Dearmore

(Aug/Sept 2012/vol. 5 – Issue 4)

It’s not terribly difficult to look back about 15 years or so and locate pretty much the exact moment when what has become known as “Texas Country” began its boom in and around college towns across the state. Not that a unique brand of country music was new to fans in Texas, of course. In the mid-to late ’90s, Willie Nelson was as cool as he had ever been, fellow ’70s trailblazer Jerry Jeff Walker still reliably proffered rowdy times for fans of all ages, and Robert Earl Keen, hot off of A Bigger Piece of Sky and Gringo Honeymoon, was playing to packed dancehall crowds of his own. But younger upstarts like Jack Ingram were quickly gathering steam, inspiring college kids across the state to pick up guitars and try their own luck at grabbing a piece of the action. One such dreamer was San Antonio-born Texas Tech Red Raider Pat Green, who began playing covers and original songs for fellow students and frat buddies in Lubbock alongside Cory Morrow and by decade’s end was one of the hottest concert draws in the state, poised for a national breakout.

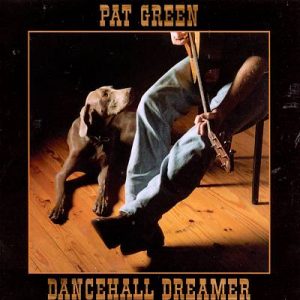

From the beginning of his rise to popularity, Green always proudly identified himself as a “Texas Songwriter” — a tag emblazoned after his name on the T-shirts and bumper stickers that sold like hotcakes from the merch table at every bar, dancehall and festival he headlined. His portfolio of originals certainly lived up to the title, with song after song celebrating the virtues of Texas, living in Texas, and listening to the music of his own Texas music heroes, and his legion of fans couldn’t get enough of it. Critics and even some of his avowed influences were less, ahem, keen on his wares, though, invariably contrasting his admittedly simple crowd pleasers against the more sophisticated offerings of elder statesman Texas songwriters like Townes Van Zandt and Guy Clark. It was an apples to oranges comparison, though, and Green himself never positioned himself as anything but a populist troubadour, his repertoire for the most part aimed at Texas country fans hungry for something a little more homegrown in attitude and rougher-around-the-edges than mainstream pop country, but still fun and catchy enough to sing (and drink) along to in venues more conducive to dancing and cheering than quiet listening rooms. He would have it down to perfection by the time of his first live album, 1998’s Here We Go, but the template was clear from the get-go with both his self-released 1995 debut, Dancehall Dreamer, and his sophomore outing, 1997’s George’s Bar.

From the beginning of his rise to popularity, Green always proudly identified himself as a “Texas Songwriter” — a tag emblazoned after his name on the T-shirts and bumper stickers that sold like hotcakes from the merch table at every bar, dancehall and festival he headlined. His portfolio of originals certainly lived up to the title, with song after song celebrating the virtues of Texas, living in Texas, and listening to the music of his own Texas music heroes, and his legion of fans couldn’t get enough of it. Critics and even some of his avowed influences were less, ahem, keen on his wares, though, invariably contrasting his admittedly simple crowd pleasers against the more sophisticated offerings of elder statesman Texas songwriters like Townes Van Zandt and Guy Clark. It was an apples to oranges comparison, though, and Green himself never positioned himself as anything but a populist troubadour, his repertoire for the most part aimed at Texas country fans hungry for something a little more homegrown in attitude and rougher-around-the-edges than mainstream pop country, but still fun and catchy enough to sing (and drink) along to in venues more conducive to dancing and cheering than quiet listening rooms. He would have it down to perfection by the time of his first live album, 1998’s Here We Go, but the template was clear from the get-go with both his self-released 1995 debut, Dancehall Dreamer, and his sophomore outing, 1997’s George’s Bar.

Although those aforementioned Green critics would readily dismiss Dancehall Dreamer and George’s Bar as lightweight compared to the then-latest sets from Keen and Lyle Lovett (Picnic and The Road to Ensenada, respectively), Green’s first two studio albums delivered — and still deliver — honest charms that transcend mere nostalgia. Green was still finding his voice as a writer and singer, but his relative inexperience was counterbalanced by the seasoned hand of producer Lloyd Maines, who brought years of experience to the table. Maines’ resume as both a guitarist and producer was already formidable, having spent years working with Lone Star legends like Joe Ely, Terry Allen, Jerry Jeff Walker, and Lubbock’s Maines Brothers Band; but his status as one of Americana music’s most sought-after producers of the last two decades has just as much to do with his knack for coaching and getting the best out of young artists.

Although those aforementioned Green critics would readily dismiss Dancehall Dreamer and George’s Bar as lightweight compared to the then-latest sets from Keen and Lyle Lovett (Picnic and The Road to Ensenada, respectively), Green’s first two studio albums delivered — and still deliver — honest charms that transcend mere nostalgia. Green was still finding his voice as a writer and singer, but his relative inexperience was counterbalanced by the seasoned hand of producer Lloyd Maines, who brought years of experience to the table. Maines’ resume as both a guitarist and producer was already formidable, having spent years working with Lone Star legends like Joe Ely, Terry Allen, Jerry Jeff Walker, and Lubbock’s Maines Brothers Band; but his status as one of Americana music’s most sought-after producers of the last two decades has just as much to do with his knack for coaching and getting the best out of young artists.  And between Dancehall Dreamer and George’s Bar, Green hit the ground running with a handful of memorable songs that continue to be staples at his live shows as well as frequently heard on radio and blasting out of countless pickup truck speakers. The debut’s “Southbound 35” and “Dancehall Dreamer” and George’s Bar’s title track and “Songs About Texas” (co-written with Walt Wilkins) in particular stand out as enduring greatest hits, both of Green’s career and the whole modern Texas country movement. And though the sing-along anthems were clearly his main forte, Green also showed early promise as a storyteller and interpreter of outside songs — as demonstrated on George’s Bar’s cover of Townes Van Zandt’s “Snowing on Raton.” (That’s Maines’ spunky daughter Natalie dueting with Green on that one, just before she found massive fame of her own as the newly recruited singer of the Dixie Chicks.)

And between Dancehall Dreamer and George’s Bar, Green hit the ground running with a handful of memorable songs that continue to be staples at his live shows as well as frequently heard on radio and blasting out of countless pickup truck speakers. The debut’s “Southbound 35” and “Dancehall Dreamer” and George’s Bar’s title track and “Songs About Texas” (co-written with Walt Wilkins) in particular stand out as enduring greatest hits, both of Green’s career and the whole modern Texas country movement. And though the sing-along anthems were clearly his main forte, Green also showed early promise as a storyteller and interpreter of outside songs — as demonstrated on George’s Bar’s cover of Townes Van Zandt’s “Snowing on Raton.” (That’s Maines’ spunky daughter Natalie dueting with Green on that one, just before she found massive fame of her own as the newly recruited singer of the Dixie Chicks.)

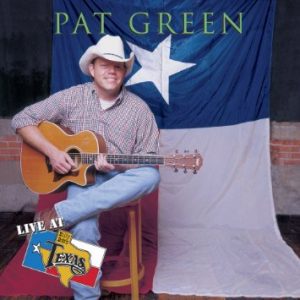

Green’s self-released, ramshackle 1998 live album, Here We Go, captured many of those early tunes in their unvarnished, beer-soaked glory. But it was the following year’s Live at Billy Bob’s Texas that set the standard for the new-school live album that begged to be screamed along with at home, college parties, and in bars across the state. The frenzy that accompanies each song can be pointed to as evidence of how quickly

Green’s self-released, ramshackle 1998 live album, Here We Go, captured many of those early tunes in their unvarnished, beer-soaked glory. But it was the following year’s Live at Billy Bob’s Texas that set the standard for the new-school live album that begged to be screamed along with at home, college parties, and in bars across the state. The frenzy that accompanies each song can be pointed to as evidence of how quickly  Green’s fan-base had grown in a short amount of time. In the album’s wake, scores of other Texas and Red Dirt artists — from established stars to newcomers — have recorded Live at Billy Bob’s albums (all put out by Smith Music Group), but Green’s was one of the first and, for years and years, the best-selling title in the series. Think of it as Texas country’s very own Frampton Comes Alive.

Green’s fan-base had grown in a short amount of time. In the album’s wake, scores of other Texas and Red Dirt artists — from established stars to newcomers — have recorded Live at Billy Bob’s albums (all put out by Smith Music Group), but Green’s was one of the first and, for years and years, the best-selling title in the series. Think of it as Texas country’s very own Frampton Comes Alive.

However much Live at Billy Bob’s seemed to capture the craze surrounding Green in full swing, though, that fervor had yet to reach its maximum madness. By the time Carry On was released in February of 2000, Green was no longer able to fit his crowds into the rooms from which he’d built up his following and lucrative business: he was a bona fide festival headliner.  That raised the stakes for his first studio album of fresh material in three years, and Carry On delivered. Maines was back to produce, but Green was clearly no longer green, having elevated the level of his writing and singing considerably without sacrificing the casual rowdiness that had already endeared him to so many. Participatory anthems like “Take Me Out to a Dancehall” and the life-is-what-we-make-it title track successfully proved Green to be a guy who still loved Gary P. Nunn as much any true-blue Texas country fan, while the intricately told story songs “Galleywinter” and the Wilkins-penned “Ruby’s Two Sad Daughters” found him confidently edging into folksier territory. There were some wildcards, too — such as the shuffling, sax-driven “Louisiana Song” and “Rusty Old American Dream,” with its mix of rock and Texas swing — but overall the album felt and sounded as cohesive as it did ultra confident.

That raised the stakes for his first studio album of fresh material in three years, and Carry On delivered. Maines was back to produce, but Green was clearly no longer green, having elevated the level of his writing and singing considerably without sacrificing the casual rowdiness that had already endeared him to so many. Participatory anthems like “Take Me Out to a Dancehall” and the life-is-what-we-make-it title track successfully proved Green to be a guy who still loved Gary P. Nunn as much any true-blue Texas country fan, while the intricately told story songs “Galleywinter” and the Wilkins-penned “Ruby’s Two Sad Daughters” found him confidently edging into folksier territory. There were some wildcards, too — such as the shuffling, sax-driven “Louisiana Song” and “Rusty Old American Dream,” with its mix of rock and Texas swing — but overall the album felt and sounded as cohesive as it did ultra confident.

Coming a year after the commercial and creative success of Carry On, Green’s next album bore all the hallmarks of a tossed-off stop-gap release: how else to describe an album of cover songs shared with his longtime friend, Cory Morrow, that was issued just months before Green’s major label debut the same year? But far from being forgettable, 2001’s Songs We Wish We’d Written was actually a rock-solid collection of well-chosen material that still holds up as one of Green’s best efforts. On the strength of the album’s signature track, the Green-sung and Django Walker-written “Texas on My Mind,” and the Morrow-sung/Darrell Scott-authored “It’s a Great Day to Be Alive” (which had recently been a hit single for Travis Tritt), the record rang true as a legitimate and fully formed artistic statement. Other songs on the album came from the likes of Van Zandt, John Prine, Billy Joe Shaver, and Waylon Jennings, all of which were rendered with the faithful reverence of genuine fans. Look elsewhere if you like your cover songs completely reinvented; Songs We Wish We’d Written, true to the modesty implied in its title, is a record made by two guys who just loved this stuff. In turn, Green and Morrow’s fans loved it, too: the independently released album climbed to No. 26 on the Billboard country chart (the highest to date at the time for either artist).

Coming a year after the commercial and creative success of Carry On, Green’s next album bore all the hallmarks of a tossed-off stop-gap release: how else to describe an album of cover songs shared with his longtime friend, Cory Morrow, that was issued just months before Green’s major label debut the same year? But far from being forgettable, 2001’s Songs We Wish We’d Written was actually a rock-solid collection of well-chosen material that still holds up as one of Green’s best efforts. On the strength of the album’s signature track, the Green-sung and Django Walker-written “Texas on My Mind,” and the Morrow-sung/Darrell Scott-authored “It’s a Great Day to Be Alive” (which had recently been a hit single for Travis Tritt), the record rang true as a legitimate and fully formed artistic statement. Other songs on the album came from the likes of Van Zandt, John Prine, Billy Joe Shaver, and Waylon Jennings, all of which were rendered with the faithful reverence of genuine fans. Look elsewhere if you like your cover songs completely reinvented; Songs We Wish We’d Written, true to the modesty implied in its title, is a record made by two guys who just loved this stuff. In turn, Green and Morrow’s fans loved it, too: the independently released album climbed to No. 26 on the Billboard country chart (the highest to date at the time for either artist).

As is still the case today, the execs on Nashville’s Music Row knew there was something going on in Texas, and decided to get creative once Green signed on the dotted line for Universal/Republic. What the label came up with in 2001 was a rarity in the country music business landscape of the new millennium: a major-label debut for an established independent artist that appealed to both seasoned fans from the grassroots regional scene as well as a whole new audience. Three Days, with its combination of Green “classics” (some re-recorded, others plucked right off of Carry On) and brand new tunes was a winner right out of the gate. The album debuted at No. 7 on the Billboard country chart and spun off a pair of modest hit singles (“Carry On” hitting No. 35 and “Three Days” No. 36), heralding Green’s transition from Texas flag-bearer to Nashville upstart.

As is still the case today, the execs on Nashville’s Music Row knew there was something going on in Texas, and decided to get creative once Green signed on the dotted line for Universal/Republic. What the label came up with in 2001 was a rarity in the country music business landscape of the new millennium: a major-label debut for an established independent artist that appealed to both seasoned fans from the grassroots regional scene as well as a whole new audience. Three Days, with its combination of Green “classics” (some re-recorded, others plucked right off of Carry On) and brand new tunes was a winner right out of the gate. The album debuted at No. 7 on the Billboard country chart and spun off a pair of modest hit singles (“Carry On” hitting No. 35 and “Three Days” No. 36), heralding Green’s transition from Texas flag-bearer to Nashville upstart.

While the Texan supporters that helped Green to national acclaim were handed only half of a new album, that new half featured some real gems, most notably the Green and Radney Foster co-written title track. “We’ve All Got Our Reasons,” another quality pick from the pen of Green’s close friend Wilkins, and “Threadbare Gypsy Soul,” a folksy duet with Willie Nelson that managed to still feel like a traditional Pat Green song, offered shining proof that Green was still very much a Texan artist plying his craft in the big leagues, and not merely a singer who happened to have lived in Texas for a spell. And as for the reheated songs aimed primarily at new fans, well — loading it with choice cuts like “Carry On,” “Galleywinter,” “Take Me Out to a Dancehall,” “Southbound 35,” and “Texas on My Mind” left little room for filler. It’s a best-of in all but name.

As Carry On primed Green for his arrival into Nashville, Three Days in turn prepped the national masses for the country-rock, mainstream assault of 2003’s Wave on Wave. Although the album overall was a good deal more heartland rock (think John Mellencamp) in style and attitude than dancehall-ready Texas country, it still sounded like Green himself was very much at the wheel, taking his music in exactly the direction he wanted it to go. As he did with his label debut, Green managed to do what is almost unthinkable now and wrote or co-wrote almost all of the songs (with the lone outside cut being another fine Wilkins contribution, the Davis Raines co-written “Poetry”). Green and rock producer Don Gehman (R.E.M., Hootie and the Blowfish) also made room for Green’s gang of Texas friends on the project, with Ray Wylie Hubbard, Ray Benson and Trish Murphy all contributing guest vocals. And for the second album in the row, Green was rewarded with genuine mainstream success: the album went Gold (a first for Green), peaking at No. 2 on the Billboard country album chart, and the metaphorically questionable title track rode its swelling, anthemic chorus to No. 3 on the country singles chart, No. 39 on the all-genre Hot 100, and gained over one million spins on radio. The following single, “Guy Like Me,” stalled just outside of the Top 30, but by then Green was already an in-demand act for opening slots on big-time tours for the likes of mega-stars like Kenny Chesney. Of course, keeping that kind of company didn’t impress Green’s more adamantly anti-Nashville fans back in Texas much, and neither did the admittedly increasingly pristine production quality of his music. But even the glossier sheen of the recordings couldn’t mask the Green-ness of Wave on Wave; thanks to songs such as “Sing ’Til I Stop Crying,” with its fiddle and piano-driven bounce, and the poetic grace of yes, “Poetry,” the album still offered most of the signature qualities that fans had come to expect from Green. All things considered, the disgruntled cries of “Pat’s lost his way” at the time seemed overly reactionary and off base.

As Carry On primed Green for his arrival into Nashville, Three Days in turn prepped the national masses for the country-rock, mainstream assault of 2003’s Wave on Wave. Although the album overall was a good deal more heartland rock (think John Mellencamp) in style and attitude than dancehall-ready Texas country, it still sounded like Green himself was very much at the wheel, taking his music in exactly the direction he wanted it to go. As he did with his label debut, Green managed to do what is almost unthinkable now and wrote or co-wrote almost all of the songs (with the lone outside cut being another fine Wilkins contribution, the Davis Raines co-written “Poetry”). Green and rock producer Don Gehman (R.E.M., Hootie and the Blowfish) also made room for Green’s gang of Texas friends on the project, with Ray Wylie Hubbard, Ray Benson and Trish Murphy all contributing guest vocals. And for the second album in the row, Green was rewarded with genuine mainstream success: the album went Gold (a first for Green), peaking at No. 2 on the Billboard country album chart, and the metaphorically questionable title track rode its swelling, anthemic chorus to No. 3 on the country singles chart, No. 39 on the all-genre Hot 100, and gained over one million spins on radio. The following single, “Guy Like Me,” stalled just outside of the Top 30, but by then Green was already an in-demand act for opening slots on big-time tours for the likes of mega-stars like Kenny Chesney. Of course, keeping that kind of company didn’t impress Green’s more adamantly anti-Nashville fans back in Texas much, and neither did the admittedly increasingly pristine production quality of his music. But even the glossier sheen of the recordings couldn’t mask the Green-ness of Wave on Wave; thanks to songs such as “Sing ’Til I Stop Crying,” with its fiddle and piano-driven bounce, and the poetic grace of yes, “Poetry,” the album still offered most of the signature qualities that fans had come to expect from Green. All things considered, the disgruntled cries of “Pat’s lost his way” at the time seemed overly reactionary and off base.

But not for long. In standard Nashville fashion, a follow-up album didn’t take long to hit shelves, and with the arrival of 2004’s Lucky Ones, even some of Green’s staunchest defenders started to have cause for concern. Gehman stayed on as producer and Green once again wrote or co-wrote most of the album, but the album’s chart success notwithstanding — it debuted at No. 2 on the country chart and launched a pair of singles into the Top 25 — the results this time around just weren’t quite as irresistible. Where Wave on Wave had sounded like an assertive charge in a new direction, Lucky Ones went straight for the middle of the road. Most of the songs were forgettable, and even the better ones were undermined by the oily slick production and lacklust-er performances. The most blatant example of the life-sucking studio sheen slathering was Green’s take on his pal Jack Ingram’s “One Thing.” When the song first appeared on Ingram’s underappreciated Electric album, it was a fiercely urgent song that owed much of its personality to Ingram’s angst-into-joy delivery. Green’s version was limp with an overly folksy feel that permeated so many of the other tunes. “College,” Green’s duet with Nashville stud Brad Paisely, was silly without being humorous and generic to the point of losing sight of its actual point of reminding people of their special days doing keg-stands and skipping class. Worst of all was “Baby Doll,” a groaner of a tune about a pole-dancer with possible daddy issues and definite low self-esteem. There may be grist there for an interesting character study, but Green and co-writer Rob Thomas (of Matchbox 20) put less depth into the story than you’d read in a TV Guide blurb for a Lifetime made-for-TV movie.

But not for long. In standard Nashville fashion, a follow-up album didn’t take long to hit shelves, and with the arrival of 2004’s Lucky Ones, even some of Green’s staunchest defenders started to have cause for concern. Gehman stayed on as producer and Green once again wrote or co-wrote most of the album, but the album’s chart success notwithstanding — it debuted at No. 2 on the country chart and launched a pair of singles into the Top 25 — the results this time around just weren’t quite as irresistible. Where Wave on Wave had sounded like an assertive charge in a new direction, Lucky Ones went straight for the middle of the road. Most of the songs were forgettable, and even the better ones were undermined by the oily slick production and lacklust-er performances. The most blatant example of the life-sucking studio sheen slathering was Green’s take on his pal Jack Ingram’s “One Thing.” When the song first appeared on Ingram’s underappreciated Electric album, it was a fiercely urgent song that owed much of its personality to Ingram’s angst-into-joy delivery. Green’s version was limp with an overly folksy feel that permeated so many of the other tunes. “College,” Green’s duet with Nashville stud Brad Paisely, was silly without being humorous and generic to the point of losing sight of its actual point of reminding people of their special days doing keg-stands and skipping class. Worst of all was “Baby Doll,” a groaner of a tune about a pole-dancer with possible daddy issues and definite low self-esteem. There may be grist there for an interesting character study, but Green and co-writer Rob Thomas (of Matchbox 20) put less depth into the story than you’d read in a TV Guide blurb for a Lifetime made-for-TV movie.

Fortunately, Green would make a strong return to form with his next album. After a three-album run with Universal that took Green from the festival fields of Texas to near the top of the charts, he moved over to the RCA imprint BNA, which released Cannonball in 2006. With Gehman at the helm again, the album unquestionably boasted the polish that hadn’t exactly been a favorable trait for Lucky Ones, yet Cannonball had a more confident, focused identity as a country-rock record that brought back a cohesive comfort that was lost in the previous collection. The opening two songs set the pace and allowed any who were leery to rest easy. The title track and the Craig Wiseman written “Way Back Texas” blended Green’s love of “Texas songs” and massive choruses with swirling fiddles and lead guitars that twisted themselves around Green’s vocals. On the album where Green welcomed more established Nashville writers than ever before (Wiseman, Jeffrey Steele, Matraca Berg, Casey Beathard), Green had figured out a way to show off his personality without singing his own words. Fans could still quibble over the merits or non-merits of some of the tunes (some folks were more gung-ho than this writer was over the singles “Feels Just Like It Should” and the schmaltz-intensive “Dixie Lullaby”), but even when Green was clearly aiming for the Top 40, he sounded fully invested in making a legitimate artistic statement again. Cannonball ebbed and flowed like a good album should, with songs like “Sleeping with the Lights On” and “I’m Trying to Find It” providing a calming dignity that made the more up-tempo numbers all the more exciting and engaging.

Fortunately, Green would make a strong return to form with his next album. After a three-album run with Universal that took Green from the festival fields of Texas to near the top of the charts, he moved over to the RCA imprint BNA, which released Cannonball in 2006. With Gehman at the helm again, the album unquestionably boasted the polish that hadn’t exactly been a favorable trait for Lucky Ones, yet Cannonball had a more confident, focused identity as a country-rock record that brought back a cohesive comfort that was lost in the previous collection. The opening two songs set the pace and allowed any who were leery to rest easy. The title track and the Craig Wiseman written “Way Back Texas” blended Green’s love of “Texas songs” and massive choruses with swirling fiddles and lead guitars that twisted themselves around Green’s vocals. On the album where Green welcomed more established Nashville writers than ever before (Wiseman, Jeffrey Steele, Matraca Berg, Casey Beathard), Green had figured out a way to show off his personality without singing his own words. Fans could still quibble over the merits or non-merits of some of the tunes (some folks were more gung-ho than this writer was over the singles “Feels Just Like It Should” and the schmaltz-intensive “Dixie Lullaby”), but even when Green was clearly aiming for the Top 40, he sounded fully invested in making a legitimate artistic statement again. Cannonball ebbed and flowed like a good album should, with songs like “Sleeping with the Lights On” and “I’m Trying to Find It” providing a calming dignity that made the more up-tempo numbers all the more exciting and engaging.

Of course, a lot of his old-school fans back in Texas — the ones who’d been crying “sell out” since Wave on Wave if not all the way back since he signed his first label deal — remained unconvinced, but the album’s debut at No. 2 proved that plenty of devotees were still very much strapped in for the ride. Sometimes for better (Cannonball), sometimes for worse. 2009’s What I’m For, Green’s second and last album for BNA, was another dip, at least artistically if not commercially. The album found him teamed with famed Nashville producer and guitar slinger Dan Huff (Rascall Flatts, Keith Urban), and there’s no getting around the fact that plenty of ball-cap-covered eyebrows in Texas were raised when the word of this pairing got around. And once “Let Me,” the banal, pseudo-soul lead single hit airwaves in the summer, the worries proved well founded. But it wasn’t so much the production that sank What I’m For (even though Huff made Gehman sound like a minimalist by comparison) as it was the frivolous, aimless quality of the songwriting. Perhaps What I’m For should have had a question mark at the end of its title, because the album suffered from an identity crisis of the highest order. In Green’s own “Country Star,” he pokes tongue-in-cheek fun at neon-chasing dreamers (“I’ll get Big and Rich rich!”), but songs like “Let Me” and especially the title track find him taking the most obvious, desperate grabs for radio spins of his career. “What I’m For” took the trendy-at-the-time “list-song” to a comical low. Proclaiming his favor for “crackers in my chili” and “getting off the Internet” reeked of a desperate artist hoping someone would confuse loosely relating to a lyric (“Hey! I know the words to the Gettysburg Address, too!”) with genuinely liking the song. At a time when the Top 10 usually consisted of at least a few bland, cover-all-the-bases, slice-of-life songs, Green titled his album after his most boring statement to date. But as if that wasn’t bad enough, he and Huff padded the album with a spit-shined, slightly reworked version of “Carry On.” When people are lost, it’s not unusual to look for a path that leads to somewhere safe. For Green, the only thing safer would’ve been a song entitled “I Love Stubbs, Shiner Bock, the Hill Country, the Cowboys, the Guadalupe and Willie.”

Of course, a lot of his old-school fans back in Texas — the ones who’d been crying “sell out” since Wave on Wave if not all the way back since he signed his first label deal — remained unconvinced, but the album’s debut at No. 2 proved that plenty of devotees were still very much strapped in for the ride. Sometimes for better (Cannonball), sometimes for worse. 2009’s What I’m For, Green’s second and last album for BNA, was another dip, at least artistically if not commercially. The album found him teamed with famed Nashville producer and guitar slinger Dan Huff (Rascall Flatts, Keith Urban), and there’s no getting around the fact that plenty of ball-cap-covered eyebrows in Texas were raised when the word of this pairing got around. And once “Let Me,” the banal, pseudo-soul lead single hit airwaves in the summer, the worries proved well founded. But it wasn’t so much the production that sank What I’m For (even though Huff made Gehman sound like a minimalist by comparison) as it was the frivolous, aimless quality of the songwriting. Perhaps What I’m For should have had a question mark at the end of its title, because the album suffered from an identity crisis of the highest order. In Green’s own “Country Star,” he pokes tongue-in-cheek fun at neon-chasing dreamers (“I’ll get Big and Rich rich!”), but songs like “Let Me” and especially the title track find him taking the most obvious, desperate grabs for radio spins of his career. “What I’m For” took the trendy-at-the-time “list-song” to a comical low. Proclaiming his favor for “crackers in my chili” and “getting off the Internet” reeked of a desperate artist hoping someone would confuse loosely relating to a lyric (“Hey! I know the words to the Gettysburg Address, too!”) with genuinely liking the song. At a time when the Top 10 usually consisted of at least a few bland, cover-all-the-bases, slice-of-life songs, Green titled his album after his most boring statement to date. But as if that wasn’t bad enough, he and Huff padded the album with a spit-shined, slightly reworked version of “Carry On.” When people are lost, it’s not unusual to look for a path that leads to somewhere safe. For Green, the only thing safer would’ve been a song entitled “I Love Stubbs, Shiner Bock, the Hill Country, the Cowboys, the Guadalupe and Willie.”

After What I’m For, Green took another three-year break from recording — and parted ways with BNA, ostensibly in a bid to put some distance from himself and Music Row and reconnect with his roots. He signed a new deal with the smaller independent label Sugar Hill and began writing songs for what’s rumored to be his long overdue “back to Texas” record (even though he never really left the state). But his first release for Sugar Hill was another covers album, the curiously named Songs We Wish We’d Written II — curiously named, that is, because the “we” this time around was mainly just Green. Morrow shared a duet with Green on Lyle Lovett’s “If I Had a Boat,” but Green goes it alone on the rest of the album except for on Collective Soul’s “The World I Know,” which features the song’s writer, Ed Roland, and a take on little known Ohioan Aaron Lee Tesjan’s “Streets of Galilee.” Even more curious is the track list; whereas the first Songs We Wish We’d Written possessed a theme in terms of the writers and sounds that were chosen, II is pretty much all over the place, as random as a shuffled iTunes playlist. But to Green’s (and the album’s) credit, it sounds like he’s having a hell of a lot more fun than he did on What I’m For. He also demonstrates more willingness to put his own stamp on the songs, as opposed to the play-it-straight approach on the first covers record. His earnest but suitably impassioned cover of Joe Ely’s “All Just to Get to You” stays well inside the lines, but his slowed-down, piano and strings take on Tom Petty’s “Even the Losers” is an unexpected but noble stab at putting a fresh spin on a classic rock tune. Not to be overlooked, Green’s interpretation of Shelby Lynne’s “Jesus On a Greyhound” is also noteworthy and commendable.

After What I’m For, Green took another three-year break from recording — and parted ways with BNA, ostensibly in a bid to put some distance from himself and Music Row and reconnect with his roots. He signed a new deal with the smaller independent label Sugar Hill and began writing songs for what’s rumored to be his long overdue “back to Texas” record (even though he never really left the state). But his first release for Sugar Hill was another covers album, the curiously named Songs We Wish We’d Written II — curiously named, that is, because the “we” this time around was mainly just Green. Morrow shared a duet with Green on Lyle Lovett’s “If I Had a Boat,” but Green goes it alone on the rest of the album except for on Collective Soul’s “The World I Know,” which features the song’s writer, Ed Roland, and a take on little known Ohioan Aaron Lee Tesjan’s “Streets of Galilee.” Even more curious is the track list; whereas the first Songs We Wish We’d Written possessed a theme in terms of the writers and sounds that were chosen, II is pretty much all over the place, as random as a shuffled iTunes playlist. But to Green’s (and the album’s) credit, it sounds like he’s having a hell of a lot more fun than he did on What I’m For. He also demonstrates more willingness to put his own stamp on the songs, as opposed to the play-it-straight approach on the first covers record. His earnest but suitably impassioned cover of Joe Ely’s “All Just to Get to You” stays well inside the lines, but his slowed-down, piano and strings take on Tom Petty’s “Even the Losers” is an unexpected but noble stab at putting a fresh spin on a classic rock tune. Not to be overlooked, Green’s interpretation of Shelby Lynne’s “Jesus On a Greyhound” is also noteworthy and commendable.

Where Green goes from here remains to be seen. Will his next album of original songs (tentatively scheduled for later this year) find him over compensating in a bid to reclaim his spot as the king of Texas country, pandering to the George’s Bar and Live at Billy Bob’s contingent of his fan base the same way those very fans accused him of pandering to the national mainstream? Or will he confidently “carry on” in the same anything goes, freewheeling direction hinted at with Songs We Wish We’d Written II and his more adventurous major label efforts (Wave on Wave, Cannonball)? At the time of this writing, it’s anyone’s guess. But this much is almost certain: waves of loyalists and skeptics alike, some of them listeners since Dancehall Dreamer, others part of a whole new generation who were first introduced to Texas country via the music of later-day stars like Randy Rogers and Josh Abbott, will be ready to pounce on it. Stay tuned.

MR. RECORD MAN’S TOP 5 PAT GREEN ALBUMS

1. Three Days, 2001

Green’s major label debut provided a great explanation to a national audience as to why Texans were bonkers for the guy, especially on the heels of his self-released Carry On, which might be a more beloved album by a lot of fans. But with selections from Carry On plus a handful of welcome new songs, such as the title track, Three Days is the album that features more Green standards than any other non-live album.

Green’s major label debut provided a great explanation to a national audience as to why Texans were bonkers for the guy, especially on the heels of his self-released Carry On, which might be a more beloved album by a lot of fans. But with selections from Carry On plus a handful of welcome new songs, such as the title track, Three Days is the album that features more Green standards than any other non-live album.

2. Dancehall Dreamer, 1995

Of course, this started it all, and features a few of the songs that would go on to be added onto multiple Green offerings down the road. In terms of the mid-90s “Texas Country Boom,” Green’s Lloyd Maines-produced debut holds up as well as any other album in the genre and still conveys an irresistible sense of carefree fun.

Of course, this started it all, and features a few of the songs that would go on to be added onto multiple Green offerings down the road. In terms of the mid-90s “Texas Country Boom,” Green’s Lloyd Maines-produced debut holds up as well as any other album in the genre and still conveys an irresistible sense of carefree fun.

3. Wave on Wave, 2003

Thanks to this revved-up collection and its infectious title track, Green finally gained the commercial success that had eluded other Texan stars in the years just prior to Wave’s release. Perhaps the biggest success of the album was inside the record’s liner notes. Each song from the Nashville-released album was written by Green and/or another Texan. The fact that the album was a chart-smash and a money-maker for the label allowed Green to keep making music with his friends until he decided otherwise.

Thanks to this revved-up collection and its infectious title track, Green finally gained the commercial success that had eluded other Texan stars in the years just prior to Wave’s release. Perhaps the biggest success of the album was inside the record’s liner notes. Each song from the Nashville-released album was written by Green and/or another Texan. The fact that the album was a chart-smash and a money-maker for the label allowed Green to keep making music with his friends until he decided otherwise.

4. Live at Billy Bob’s Texas, 1999

To this day, a Green show at the legendary Ft. Worth venue is a guaranteed chance to see the Fire Marshall shove people away from the door. Green’s second live album captures him at the peak of his surging regional popularity, knocking out a crowd-pleasing set of greatest hits (in Texas, at least) in front of a massive and wild audience.

To this day, a Green show at the legendary Ft. Worth venue is a guaranteed chance to see the Fire Marshall shove people away from the door. Green’s second live album captures him at the peak of his surging regional popularity, knocking out a crowd-pleasing set of greatest hits (in Texas, at least) in front of a massive and wild audience.

5. Cannonball, 2006

Cannonball is perhaps the only Pat Green CD that fraternity brothers would steal from their mom’s Escalade — but that’s not a knock on the album’s quality. The ability to rebound from the disappointing Lucky Ones with such an enjoyable album mixing songs written by Music Row vets as well as with his long-time friends was impressive, showing fans of both old-school Green and mainstream Green that he still knew how to throw down.

Cannonball is perhaps the only Pat Green CD that fraternity brothers would steal from their mom’s Escalade — but that’s not a knock on the album’s quality. The ability to rebound from the disappointing Lucky Ones with such an enjoyable album mixing songs written by Music Row vets as well as with his long-time friends was impressive, showing fans of both old-school Green and mainstream Green that he still knew how to throw down.

No Comment