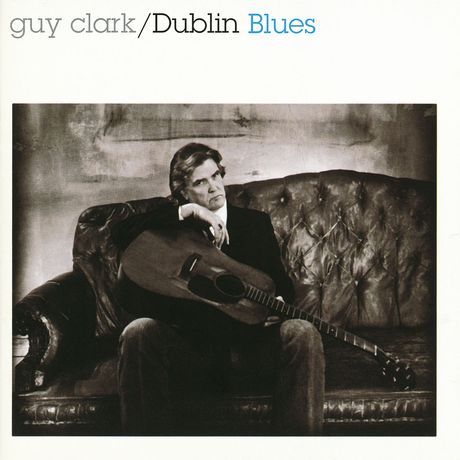

GUY CLARK

Dublin Blues

Asylum/Elektra (1995); Dualtone (2016 vinyl reissue)

Guy Clark passed from this world in the early morning hours of May 17, 2016. The loss is fresh and deeply felt for anyone who’s ever been in love with the thread of wise, subtle, lyrically rich country and folk music that he embodied and advanced during his time on earth. A proper summation of his career could fill a book, and expanding upon his legacy and influence on the writers around him and after him would spill over into a second. But for the moment, let’s contend with just one of his notable life achievements, the 1995 album Dublin Blues. Released 20 years after his first album and just shy of another 20 before his last, it’s a mid-career record that holds up as one of Clark’s absolute best — and one handily bookended by two of the Texas legend’s most acclaimed masterpieces.

First off, a little context. If you’re generally unaware of his work and haven’t caught up through the flurry of hasty but heartfelt tributes that have sprung up on this site and others, Guy Clark was a songwriter from Monahans, Texas that came of age during the outlaw/progressive country movement of the ’70s. He was already a bit of a legend when his stately, stripped-down-yet-towering 1975 debut Old No. 1 came out; several of the songs had already been hits (or at least regional favorites) in the hands of other artists (most notably, Jerry Jeff Walker). The looser, funkier Texas Cookin’ hit the shelves the following year and, though it sold modestly by country-star standards, it cemented Clark’s reputation as one of the best and most distinctive narrative singer-songwriters in an era full of them.

But in an unpredictable business, luck and trends and other intangibles can make one era’s rising star the next era’s niche artist. Clark jumped from RCA to Warner Bros. in the late ’70s, and his next three albums were peppered with classics but didn’t get much market traction and faded out of print. Next came his signing to the folk-friendly Sugar Hill label for 1988’s Old Friends, a warmly modest record that didn’t make too many waves even by low-key folkie standards. But a few years back in his writing room and a jump to the more aggressive and diverse Asylum/Elektra imprint made a big difference: 1992’s Boats to Build was livelier, funnier, and more resonant than most of his post-70s output, with better promotion and distribution in an environment that was growing friendlier to niche marketing. More of the world — at least that portion of it with a taste for thoughtfully crafted acoustic music — was able to see Guy Clark as both a returning legend and someone doing some of the best work of his already-long career. The label doubled down on the rejuvenated artist with 1995’s Dublin Blues, which was greeted with more anticipation and interest than Clark may have seen in over a decade.

Any doubt that his personal renaissance might be short-lived was dashed in the opening lines of the opening title track. “Well I wish I was in Austin, at the Chili Parlor Bar/Drinkin’ Mad Dog margaritas and not caring where you are,” Clark near-whispered, and it just got better after that indelible and oft-quoted line. A subtle but stoically devastating romantic epic that pondered the nature of love, pride, art, and distance, every verse dropped like a challenge to songwriters around the world: can you top this? It begged to be replayed, quoted, and reckoned with by anyone who heard it, an itinerant landmark for fans and fellow artists alike. Feel free to pause for a bit and listen to it by whatever means available if you’ve never had the pleasure.

Inevitably, things get a little more down-to-earth as the record moves on. “Black Diamond Strings” extols the pleasures of cheap guitars and even cheaper strings (of course Clark was among the talented few that could make those still sound good), and the often-covered “Stuff That Works” muses over the pleasures of old work boots, older guitars, and beloved friends and wives. A winsome vein of hope runs through the love-struck “Tryin’ to Try” and the more-celebrated “The Cape,” a unique number about a kid with a “flour sack cape” who can’t stop trying to literally fly no matter how many painful trips he takes from the garage roof to the ground below. “He did not know he could not fly/so he did.” Endings don’t get much happier.

Clark’s long marriage to his famously talented and complicated wife Susanna (who preceded him in death in July of 2012) was always fertile ground for his songwriting, and the gentle needling in “Shut Up and Talk to Me” and the ironic post-argument admiration in “Baby Took a Limo to Memphis” hold up pretty well as examples of how sincere affection and everyday dust-ups can co-exist. They weren’t the deepest of wells, but served as an engaging peek into a storied relationship. The offbeat humor of “Hangin’ Your Life on the Wall” remains a reliable pick-me-up, and “Hank Williams Said It Best” picks up a haunting momentum as a master writer basically plays a word game with himself. “One man’s rock is another man’s sand, and one man’s fist is another man’s hand/One man’s tool is another man’s toy, and one man’s grief is another man’s joy,” and so forth, getting deeper and better as it goes.

Despite all its pleasures, the record never quite reenters the stratosphere inhabited by that opening title track until the very last song. Clark had already recorded his composition “The Randall Knife” before, on 1983’s Better Days. But much like his father’s titular handmade knife that begged to be rediscovered by a son trying to find a way to properly grieve, this treasure deserved to come back out of the drawer. The version “The Randall Knife” on Better Days is more than adequate, but herein lays a rare case of the remake being superior to the original. The Dublin Blues version is starker in sound, more deliberately phrased, the grief and gratitude burnished and enriched by the years. And it’s a testament to the impact Guy’s father had on his life and heart that the specifics of his memory could still bring out the awe and sadness so tangible in his voice, a dozen-plus years after he’d first committed it to song.

It will be ages before the grief, awe, and gratitude we’ve reserved for Guy Clark will wear off. His best work — meaning dozens of immortal songs — belongs right up there with The David, the Mona Lisa, and Doc Watson’s lonesome take on “Columbus Stockade Blues.” Shortly after the release of Dublin Blues, Clark’s late ’70s and early ’80s output got a proper re-release on the compilation Craftsman. His spot up near the top of the modern songwriting pantheon reclaimed, both his productivity and the audience interest in his work hit a new peak. His first proper live album, Keepers, renewed his relationship with Sugar Hill Records in 1997, and he blazed into the new millennium with great records like Cold Dog Soup, The Dark, Workbench Songs, and Somedays the Song Writes You. His last proper album, 2013’s My Favorite Picture of You (Dualtone), was widely considered among his best. Calm but never lazy, deep but never pretentious, prolific with rarely a word wasted, Guy Clark was a poet right up to the end. — MIKE ETHAN MESSICK

No Comment