By William Michael Smith

(LSM March/April 2011/vol. 4 – Issue 2)

With the February release of Blaze Foley’s 113th Wet Dream, a stellar new tribute album by Gurf Morlix, plus the long-in-the-works documentary Blaze Foley: Duct Tape Messiah finally reaching the public, the late, great Foley is suddenly receiving more exposure than he ever did while he was living.

So why does a guy who, at the time of his death, had only ever had 200 copies of one album released, deserve a full-fledged documentary? Duct Tape Messiah producer Kevin Triplett, who has been working on the film since shortly after hearing about Foley in 1996, admits frankly, “It’s not like this is going to be some life of Bob Dylan kind of huge film.” And yet, if ever there was a poster child for the “Keep Austin Weird” ideal, Foley was it.

Austin has always been filled with off-kilter characters, and Foley ranks near the top of the heap on any rational scale of weirdness. Virtually homeless his entire adult life — he and a girlfriend once lived in a Georgia tree-house for nine months — Foley existed by living off others for most of his 39 years, sleeping on couches and in spare bedrooms, even bunking in abandoned cars and, most notoriously, under the pool table at his ostensible headquarters, the Austin Outhouse, where he was known to sleep off many a drunk.

According to friends and supporters, Foley, who mimicked the fancy “Urban Cowboy” set by using duct tape on his boots and Western outfits, could be either a most lovable, caring person or the mean, argumentative, button-pushing local drunk. He was certainly no stranger to the Austin police, and it was nothing out of the ordinary for Foley to be 86ed from the bars he frequented.

Born Michael David Fuller on Dec. 18, 1949 in Malvern, Ark., Foley was also known for his hard luck and bad timing. He would find flush backers to finance a session, only to have some catastrophe strike. The masters for his first album were reputedly seized by the FBI when the executive producer was involved in a drug bust. The tapes from his second album were stolen from a station wagon he was living in. And the masters for Wanted More Dead Than Alive were mysteriously lost shortly after Foley’s death. Squandered opportunities, intentional career self-destruction, and fractured dreams became integral to the legend of this songwriter, who was shot to death in Austin on Feb. 1, 1989, while defending an elderly neighbor from an abusive son. Foley and the man had previous altercations, and Foley had once been arrested for driving the man off his neighbor’s property with an ax handle. Friends were outraged when Foley’s killer was declared not guilty due to self defense.

But personality quirks, unconventional lifestyle, and a lifetime filled with erratic, self-destructive behavior can’t overshadow Foley’s small but intense body of work, which ranges from beautiful, absolutely forlorn lost-love songs to hilariously inventive off-center tunes and bitter political commentary. Although Foley’s entire publishing catalog only spans 65 songs, he has been covered by Joe Nichols, Lyle Lovett, John Prine, Willie Nelson and Merle Haggard. Haggard’s cover of “If I Could Only Fly,” off of his 2000 album of the same name, is one of the premier recorded performances of his career. Lucinda Williams added to Foley’s posthumous legend with her song “Drunken Angel,” and Townes Van Zandt paid a touching tribute to Foley with “Blaze’s Blues” on 1994’s No Deeper Blue, Van Zandt’s final album.

Van Zandt, whom Foley met during an ill-fated trip to New York City to open for Kinky Friedman (he was booted off the stage mid-set), was at once Foley’s biggest champion and a toxic influence. According to longtime Foley sideman Morlix, Blaze fell under Townes’ spell and sought to emulate the mercurial Texan.

“Townes was just one of those people,” Morlix notes. “I saw all kinds of people fall under his spell. There was just something very engaging and compelling about him that made a lot of people want to be like him. Blaze drank, but he didn’t become a binge drinker until Townes introduced him to vodka. They’d get to drinking vodka and those binges could last for days. It was very debilitating for both of them, and it hurt to watch.”

East Texas native Triplett notes he’d never heard of Foley until he moved to Austin in 1995. “When I got to Austin, my cousin and a friend were recording a Blaze tribute album, just basically trying to get all 65 of his songs covered, when they first told me about him,” Triplett says. “At first, I just thought they wanted me to invest in their recording project.

“I have to be honest, I didn’t really even connect with most of the songs at first,” Triplett continues. “His music hadn’t had much reach, and outside Austin he was virtually unknown. So the obvious question was, why a documentary on Blaze? I had no good answer in the beginning. But I eventually grasped that he wrote good songs. Then it dawned on me that he wrote those songs directly about his life and that he had lived a life that had a lot of meaning. He was one of those people who didn’t seem to ever look back. Add to that the fact that he died protecting someone from a wrong, and that seals his legend as far as I’m concerned. And that’s what makes it a worthy project and a film of value.”

Triplett traveled to a dozen states and conducted 127 individual interviews for the film, eventually compiling over 300 hours of footage. Merle Haggard is the only “celebrity” in the film.

“I’m actually proud that Merle is the only famous person in the film,” Triplett says. “But I’m glad we got him.”

Longtime Foley associate Lost John Casner provided the connection to Haggard.

“Around 2000 Merle had cut ‘If I Could Only Fly’ after hearing it during some Willie Nelson sessions at Pedernales Studios, and he told Willie he wanted to cut it,” Triplett explains. “Once we got into filming, Merle came through Austin several times but we never got him. But apparently Merle wanted to know everything he could find out about Blaze, and he would hook up with Casner when he came through town. So Casner was on Merle’s bus and told him about the project.

“We sat up our equipment on a street corner across from Merle’s bus and waited,” Triplett continues. “It was about three hours before Merle got comfortable I guess, but eventually he decided to walk over and talk to us. He was very wary and hesitant at first, but once he realized we were for real he opened up and said some truly beautiful things. The footage shows that Merle really thought a lot of Blaze.”

In the film, Haggard calls Foley “a hero” for the way he lived and died.

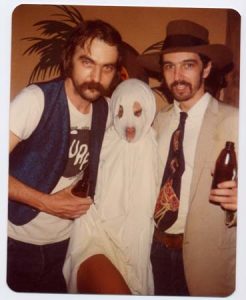

Blaze Foley with Gurf Morlix — dressed as each other — and unknown ghost on Halloween. (Courtesy Gurf Morlix)

Triplett will be touring with the film throughout the coming year, with as many showings as possible coupled with sets by Morlix performing Foley’s songs. He is also entering the film into numerous festivals and plans to do screenings in Europe in the fall.

Meanwhile, Morlix is busily promoting his Foley tribute album with shows of his own in addition to his appearances at the film screenings.

“Not to overstate it,” the taciturn Morlix says, “but this is noble work, and he was a noble man. Blaze Foley is worth knowing and remembering.”

No Comment