By Richard Skanse

October 2003

Friday, Sept. 19, 2003, was the day Robert Earl Keen was supposed to get to have his cake and eat it too. He was scheduled to play an evening set on one of the two main stages at the second annual Austin City Limits Music Festival — the perfect opportunity to break in some of the wilder songs from his brand new Farm Fresh Onions, the wildest album of his career, in front of several thousand fans. And he’d happily play all the crowd favorites, too, because for once he wouldn’t be torn between the familiar struggle of giving the people what they want (party songs!) and the quieter, more introspective songs that represent his best work. That’s because he’d also get to play an entire set of the latter earlier in the day at a smaller stage sponsored by BMI to spotlight singer-songwriters. On paper, it promised the best of both worlds.

It didn’t quite pan out that way though. Oh, the evening show was a success, with thousands singing along with Keen to every word and rocking out with the band to “The Road Goes on Forever,” “Dreadful Selfish Crime” and all the other anthems, while hundreds of out-of-towners got a taste of homegrown Texas Hill Country roots rock at its finest. The afternoon set on the BMI stage was a keeper, too — but any hope Keen had of sitting down to play his folksier fare in an intimate setting went out the window the minute he saw the crowd.

“The BMI people had told me, ‘It’s just going to be a little thing, under a little shade tree with just a few people there,” chuckles Keen. “Then I stepped up there, and there was a couple thousand people all the way around the stage. That was a shock. I threw everybody off — me, the sound people, even the BMI people. Of course, I couldn’t really do the real quiet stuff then, because you have to play to the crowd at that point.”

All of which Keen is good and used to. “There’s always that battle,” he sighs good-naturedly. “A big part of me always likes to just have that real acoustic, sit-down kind of deal. And then I get overwhelmed by the crowd, and go for plan B.”

“Plan B,” it just so happens, has made Keen far and away one of the most successful entertainers on the Texas music scene. While he’s never found a foothold in the mainstream quite like his old A&M buddy Lyle Lovett, Keen has a national cult following across the country that has stuck with him through thick and thin for more than a decade, while in Texas he’s been a bona fide headliner for years, his live performances the stuff of Lone Star legend and his songs deemed cover-worthy by everyone from Joe Ely to Nanci Griffith to the Highwaymen (Willie Nelson, Kris Kristofferson, and the late Waylon Jennings and Johnny Cash, who named their third album The Road Goes On Forever). All that, mind, before the brand new generation of Texas troubadours who seized on Keen’s popularity with the frat crowd set and turned an approximation of his sound into a bankable franchise.

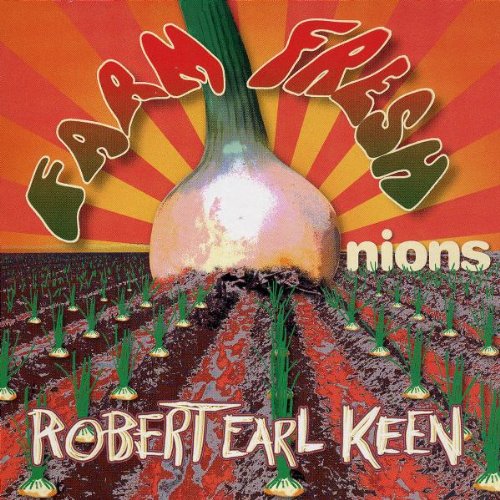

Keen responded to the blossoming Texas music revolution by launching his own Texas Uprising package tour, while continuing to put out records like 1998’s Walking Distance and 2001’s Gravitational Forces (both for major labels, Arista and Lost Highway, respectively) that consistently proved he could still deliver anthems as punchy and rabble-rousing as anything offered up by his later-day imitators while simultaneously penning songs like “Road to No Return” and “Wild Wind” that reaffirmed his right to be named alongside his own songwriting heroes. Farm Fresh Onions, his first release on his own Rosetta Records label (in affiliation with Audium/Koch), adds several more winning songs to both categories (“Furnace Fan,” “These Years”), but Keen’s never written or recorded a song like the psychedelic-freak-out title track before. It may leave some of his fans scratching their heads, but Keen and band sound positively recharged, like they’re having the time of their lives. Think of it as Keen’s “Plan C” – when the road goes on forever, sometimes you’ve gotta take a few detours to rediscover why you’re making the journey in the first place.

And if you want to grow you hair out a little bit while making those detours, who’s gonna stop you?

You know, a funny thing I kept hearing at the Austin City Limits Music Festival was how Steve Earle was clean-shaven, but Robert Earl Keen looked like long-haired, shaggy mountain man. People were saying you’d switched bodies.

[Laughs]

It’s fitting, actually, because you kind of look like this new album sounds: wild and unkept. Did you plan it that way, like, “I need to grow some rock hair to complement my rock album?”

Hah. No. It’s just how it came out. I guess it’s just all part-and-parcel to the whole thinking process. When I made this record, I just wanted to make a fun, colorful record. And the more I got into it, the more colorful I wanted it.

Was Farm Fresh Onions as fun to make as it sounds?

Oh yeah. I think that’s a big part of it. I got [guitarist] Rich Brotherton to produce it. We’ve been working together for 10 years, so he knows what I like and I know what he likes, and it was just a perfect match. I’ve enjoyed working with all of those people like Gurf Morlix and Lloyd Maines in the past, but I think Rich is overlooked as a great guitar player, and he’s got a giant musical mind. I was like, “Why would we go looking for a producer when we’ve got this guy right here?” And I was really happy with the results.

Two years ago, right after Gravitational Forces came out, Texas Music magazine did a cover story on you, and in it you said you had a “strong suspicion” that your next record would be “very acoustic and wooden.” Did this album start out that way and then kind of just go off the tracks and turn into a rock ‘n’ roll record?

I just didn’t know at the time. I think right after Gravitational Forces I was kind of thinking in terms of how I’ve always wanted to do a bluegrass sort of record. But it’s right in the middle of everybody doing a bluegrass record, so, always being contrarian to everything, I didn’t want to do what everybody else was doing. So when we started doing this record, the songs just came out like this. They were just more funky and junky. As a matter of fact, in my notebook, that’s what I wrote on the second page, when I was writing about what I wanted to do with this record. I wrote in big letters: “Funky and Junky.”

So does that stem from a kind of, “what have I got to lose?” attitude? Has that kind of wild streak always been with you in the studio, or is something relatively new?

You know, for a while there I was really trying to second-guess what I thought people wanted, or what I could make things sound like, what might fit in more. And I’ve finally just totally accepted the fact that I don’t always fit in, and I just need to do what I want to do and what feels good at the time.

So you made a record that doesn’t fit in with anything – even your own catalog.

[Laughs] Right. I don’t think so. But then again, some people say that they feel like this is the quintessential Robert Earl Keen record. To me, it’s just a record that I made with the band, and I really like it. I play it back, and I don’t wince or go, “Damn, I should have done that.” I don’t have any regrets about this one. I kept telling myself, “Hey, I can do anything I want to do here.” But it steel feels like me. I mean, I have my own boundaries within my writing style, and I just tried to expand some of them.

Speaking of boundaries, I would assume that you’d be past this sort of thing at this point in your life, but I have to ask: what were you tripping on when you wrote “Farm Fresh Onions?”

[Laughs] Well, I tried to keep explaining this to the people who were working on the album cover. I was like, “Come on, you guys! Don’t you know what ‘visual echoes’ are? That’s what I’m looking for here!” And they’d go, “No.” And I said, “Well, obviously you’ve never done any hallucinogenics!” And they said, “No, not really.” But I finally found a guy who did understand what I wanted, and that was the guy who ended up putting together the whole package. We spoke the same language — you know, dripping ceilings and all that kind of shit.

Did you find him in a halfway house?

Oh no. He’s a real artist, but he just has that kind of experience. It’s hard to explain to somebody who hasn’t.

How do you even begin to explain the song itself? It sounds like Guy Clark’s “Home Grown Tomatoes” crossed with the Rolling Stones’ “Gimme Shelter.”

Yeah. Well, the starting point with the song was, I brought this sack of grapefruits back from the valley. It was one of those mesh sacks. And my wife picks this bag up and she looks at it like she’s had some kind of epiphany, and she says, “You’ve got to write a song about this.” I said, “What, that bag?” “No, no …” And she turns it around and it says “Farm Fresh Onions.” I said, “Why?” She said, “Believe me, you just have to.” So I said “fine.” I really was just trying to write a song to appease my wife. And I thought, wow, this is really fun. Instead of trying to write something you think somebody wants, it’s more fun when they say, “Write me a song that says ‘farm fresh onions.'” Like, hey, I can do that! It’s nice and wacky. As opposed to how, you know, anytime someone finds out you’re a songwriter, they reference their own words and say, “You know, that’d make a pretty good song.” And you have to tell them, “No, it wouldn’t.” But ‘farm fresh onions,’ that does make a pretty good song, as far as I’m concerned. Especially as I got deeper into it. It got more and more fun as I went along.

Well, what’s it about?

Truth! When you peel away all the layers, what’s there? The truth.

What about my favorite song on the album, “Beats the Devil” — you have a story behind that one? It really seems like a great throwback to “Blow You Away” and “Dreadful Selfish Crime,” those kind of songs.

Well, it is a common theme: never stopping, the whole wandering lost soul kind of thing. Where did that come from? I don’t know. I just sat down and wrote it. That was truly one of those 20-minute songs that just falls out.

Do you get a lot of those?

Not very many. One out of 20 maybe.

Is writing for you always a labor?

You know what? Putting on my socks is labor. I am so intrinsically lazy that I can’t even start to tell you what is work and what is fun. It’s all work. [Laughs]

You started out on Sugar Hill, a national independent label, then signed to Arista for two records in the ’90s and most recently with Lost Highway for Gravitational Forces. Now you’re back on the independent route. Was Lost Highway just the last straw for you as far as major labels go?

I don’t know. I didn’t have very much luck in major label land. I felt like we were just off-center always, somehow. I try to remain naïve enough and idealistic enough to think that people don’t actually think these things out, but I’m also paranoid enough to think that they might be thinking these things out. Does that make any sense? So with that in mind, I’d like to just say that, you know, shit happens. But the fact is, it just kept happening, so I decided in the end that somebody must want it to happen this way, and I can’t play this game any more. Because I can’t figure it out.

What’s your set-up now, with Audium and Koch? Do you own your own masters, and they license the album?

Right. I did some records that way with Sugar Hill, too. But I couldn’t do that with the major labels. They won’t let you.

Speaking of Sugar Hill … where did this Robert Earl Keen “best of” they just put out come from? The Party Never Ends: Songs You Know From the Times You Can’t Remember? Did you see that one coming, or was that one of those, “Oh God, why did you did you do that?” kind of deals?

It was a why-did-they-go-and-do-that kind of thing. I mean, I called them up and went, “Come on! What are you doing to me?” They said “Oh, it’s not on purpose, it just fell out this way and stuff.” And I just said, “OK.” I mean, we were friends for so long, I’m not going to shake it up over this. But see, that’s the magic of changing labels and stuff. I was never at one place long enough for somebody to actually get a grip on a kind of a best-of package on me. And I thought, I’m skipping along here pretty good, getting away with not putting out a best of. Sometimes they come in handy — I’ve got a best of Bob Dylan that’s an awesome record, right? But I don’t like to buy a lot of best ofs, I like to go out and find the real record. But evidently, a lot of people do, and labels love them; as soon as they get two records on you, they’ll do one. And in my naïve way, I always thought that the artist has something to do with that, and that’s not true. Most of the time the artist probably has nothing to do with it, and it’s all about the record company and selling and packaging and all that shit. Which is a shame because it really takes away from your view of the artist. Some of my favorite artists, they’ll do three records and then come out with a best of, and I think, “Come on! Can’t they make another record? Can’t they go out and just do some tuba songs or something?” So the best of thing is discouraging to me. I was lucky that I got away without having one for so long … but now I got nailed.

It really doesn’t seem very comprehensive …

It’s from three records! They did come to me and ask if I wanted to license them some songs from my other records, and I told them no. Because I didn’t want a best of! So, it’s really … what’s that word they kept using all the time with those books? “Unauthorized.” But … it’s out of my hands, dude!

Speaking of things being out of your hands, did you want to cry when the Dixie Chicks covered “Merry Christmas From the Family,” only to have Rosie O’Donnell stink it up by talking in the middle of it?

[Laughs] Oh, I don’t know. That did nobody any good, I know that. It’s like, if that had been on a real record, I could retire. But it’s not on anything. It’s on some bullshit thing [Another Rosie Christmas, 2000]. But, whatever. You know, I’m pretty judgmental in general about stuff, but I’m never too judgmental about people doing my songs. It usually makes me happy.

Any covers coming up that you know of?

Yeah, the Greencards, a bluegrass band in Austin, just did a cover of “Love’s a Word I Never Throw Around.” They just sent it to me today, so I’m looking forward to hearing that. On a bigger scale, I don’t know what’s coming down the pike. It’s weird — you’d think people would call you up and tell you, but a lot of times they don’t.

You’ve got a gig in College Station this month. Given you’re A&M background, are your shows in College Station like the eye of the storm as far as the whole wild Robert Earl Keen crowds go?

No, not really. They were at one time, but not so much any more. We’re playing to really almost another generation. I mean, our crowds are really varied these days. It’s weird. You know, for a while there, when we had so many fraternity guys … I’d never been in a fraternity, and it kind of crept up on me. And I didn’t even know it was happening. Then I realized it was a big part of our audience. But now it’s dissolved to some degree. We still get handfuls of those guys, but they’ve moved on, and now we get this really … just, everything from junior high school kids to really old people.

That diversity’s got to be a good thing, no?

I guess. But it’s like, I don’t really even know who I’m talking to anymore. When I started out, I was really talking to people about my age – the age of sarcasm, with a pinch of cynicism. That was my whole approach, and I felt real comfortable with it. But now it’s gone all over the place. I guess that’s why I can do a record like Farm Fresh Onions, though.

I guess it throws you for a loop when you go out on stage and see a bunch of families.

Yeah. It’s just weird. But they seem to like it. I used to be kind of afraid when I’d see an older group or families, because I’d think, “I’m going to offend these people – they just stumbled in here.” But now, I have to say, I do know that they came here on purpose.

Are you still in the management game?

Yeah, to some degree. We still manage Rodney Hayden. I think we’re doing a great job. Artistically, I he’s doing great. Of course monetarily, that’s another story. But the two records he’s put out are great records. Of course, I’ve had a lot to do with them, so I would say that, but the fact is they do sound good, and they’re true to Rodney. So I’m still into that, and I’ll still do it as long as I can do it as kind of like a mentor thing; just help somebody from stepping in the big traps.

But doesn’t that get old? I mean, a lot of those frat guys you were talking about a minute ago went on to make their own records. Do a lot of young guys hit you up for advice all the time?

You know, if they have a few pointed, specific questions, I can certainly answer them. But there’s always the people who show up backstage and go, “Here’s my first CD, what should I do?” And you just throw your hands up and go, “Hell, I don’t have any idea.”

No Comment