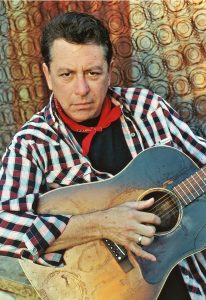

By Richard Skanse

“Hey, what ’cha know?”

It’s 10:30 a.m., and Joe Ely, his signature West Texas greeting as cheerful as ever, is all coffee’d up and ready to seize his day — which after a casual catch-up phoner with Lone Star Music will apparently entail gassing up his mower, cutting his grass, and, more likely than not, popping into his home studio to whittle away at any one of the handful of different recording projects he currently (always) has in various stages of development. The prolific performing songwriter will be hitting the road again soon enough, “buzzing around” Texas and the rest of the country both on his own in support of his latest release, last October’s Panhandle Rambler, and as part of the “Southern Troubadours” package show with fellow Texan Ruthie Foster and Mississippi’s Paul Thorn. But other than this morning’s interview, the newly appointed Official Texas State Musician of 2016 has the rest of this very pleasant Austin day in early March to call his own.

Ely, who turned 69 years old February, has never been a resting-on-his-laurels kinda guy. But if he was, he’s already collected enough in the young new year alone to make quite a bed. In addition to his Official Texas State Musician title (which was actually bestowed upon him last year, at the same time as 2015’s honoree, Jimmie Vaughan), the legendary Flatlander and Lubbock-reared roots rocker was saluted with a tribute concert during January’s MusicFest in Steamboat Springs, Colorado, and February found him inducted into the Texas Heritage Songwriters’ Association Hall of Fame. Panhandle Rambler, meanwhile, has collected even more glowing reviews than usual for Ely, who’s been making critically acclaimed albums now for the better part of 40 years. He’s been especially prolific over the last 15 years, releasing handfuls of records both brand new and culled from his archives as a solo artist and with the Flatlanders (Butch Hancock and Jimmie Dale Gilmore), and even publishing his first novel, 2014’s Reverb. And from the sound of his plans for the rest of 2016 and beyond, he’s still got plenty more in the hopper to keep him busy for well into his next decade — provided, of course, that we all make it through the next election OK.

So I’ve interviewed you a lot of times over the last 20 years, but this is the first opportunity I’ve had to talk to you during your term as our Official Texas State Musician. Before going further, are there any new etiquette rules I need to be aware of?

[Laughs] You know, I’m still trying to figure out what I’m supposed to do with that title. I proposed a couple of things when I was in the Capitol building when they were giving me the proclamation. I offered to, if they would supply the machinery, I offered to mow all the grass from Lubbock to Amarillo on Highway 87, or Interstate 27, but that didn’t go over too well. So I’m just waiting to see if any … I was also going to remove all the speed bumps in the state of Texas; I thought if I had the power to do that, I would use it for that purpose. But so far that hasn’t gotten any response.

Well, damn. What power do you have?

I don’t know! I think about the same that I’ve ever had. Just try to write a good song, and try to go from there.

You’ve been a Texas musician your entire life. But now it’s official.

Now it’s official, that’s right. That’s the only difference a proclamation makes. But it’s nice to be recognized by, you know, the Texas Legislature. I’ve been a Texan all my life, and that’s what I’ve been doing, writing songs. So it’s a nice gesture and I’m, you know, probably going to keep on doing that for awhile. … Oops, hello?

I’m still here. Can you hear me?

OK. Yeah, I can. Just heard a weird sound there for a second. Sounded like a mosquito with a bell on its ass.

Oh, sorry, that was just a text coming through on my phone. You know the commercials always show all the things you can do on an iPhone, but they never show how annoying it is when you’re trying to talk or type on it and it interrupts you with something else.

[Laughs] Exactly. In fact, I think it’s on the Satisfied at Last record, right in the middle of one song you can hear … I guess while I was recording it at my studio, I had my phone on, and I was recording a vocal or something and I didn’t hear the phone ring. But after I had mastered the record and everything, I realized that I had recorded my phone sound onto my vocal track. And so every time I hear it now I go for my phone and then I realize it’s on the recording.

Now I’m going to have to go back and try to find that on the album.

Yeah. It’s like when I had a bunch of dogs back in the ’80s and ’90s, there’s quite a few recordings that have dog barks on them. But I kind of relish the thought of having those on there. Oh and there’s a wild turkey gobble somewhere on Panhandle Rambler, but it fits in so much with the track that you can’t really pick it out. But I found it when I was mastering the record.

A couple of weeks ago, you were inducted into the Texas Heritage Songwriters’ Association Hall of Fame at a big to-do held at the Moody Theater in Austin. As nice as the recognition is, is there an element of squirmy discomfort for you when you’re being honored at a big public event like that? Or do you just let yourself feel tingly good the whole night?

Well, it is slightly uncomfortable, because I’m not used to that — that’s not an everyday occurrence! It’s like when I was up at the MusicFest deal in Steamboat Springs, Colorado, in January, and they kind of honored me at a deal there where they had about 20 different people play my songs, and I sat in the audience while they were playing them. And that was a little uncomfortable, just because as I would hear somebody interpret a song, I was thinking, “Why didn’t I do it like that?” [Laughs] I would hear people’s interpretations of all these songs that I had written over the years, and it gave me a whole different perspective of how and why and all the things about writing the songs in the first place.

Did any of them stand out in particular for you?

I can’t really pick one out right now; I’d have to sit and think about it. But I did hear versions of songs with slightly different rhythms and ways of playing where I thought, “That’s pretty nice, I think I’ll use that the next time I play that song myself.” Stuff like that.

Speaking of different ways of interpreting your songs, your full band shows are pretty legendary, but the last few times I’ve seen you have all been stripped-down acoustic duo affairs, either with Joel Guzman on accordion or Jeff Plankenhorn on guitar and Dobro. How long have you and Plankenhorn been playing together now?

I’d say probably about seven or eight years. The first time was when we were having a little thing together out at my house, playing a few songs under the tree raising money for a benefit that Stephen Bruton put together. And then he had that big show down at the lake that they filmed for a documentary [Road to Austin], with Bonnie Raitt and Kristofferson and all the local great musicians and writers and guitar players. I’d play one song with [David] Grissom, one song with Joel, a lot of different players, but that was kind of when I first played with Plank.

How long does it usually take you to really break in with a new guitarist? Where you know you’ve found just the right one?

Well, a good player who’s been playing a long time can pretty much just hear something and know what to play on it. But it takes years to actually get to that point where you’re almost sharing the same mind. There have been many times where I’ve been playing with Plank, or David Holt or Joel Guzman or Grissom, and I’ll play something and just kind of think of what the feel might be after that, or the solo, and then they do it and it’s almost like they’re reading my mind and I’m reading theirs, because they know how to sequence different riffs and everything. And then I know what I want to hear next. So it’s a strange feeling … it’s a certain kind of guitar telepathy that just happens after you’ve been playing together for a long time.

You’ve played with so many great guitarists over the years, and all of them have had pretty distinctive styles to call their own. It’s clear enough how those different styles can inform a record or performance, but have you ever noticed your songwriting directly shaped or influenced by whoever you’re playing with at the time? I guess the most obvious example would be when you started working with Teye in the ’90s and that Spanish/flamenco sound came to the fore on Letter to Laredo, but even before that — your ’80s band with Grissom, Davis McLarty and Jimmy Pettit must have felt like driving a whole different car than the Jesse Taylor/Lloyd Maines rig you had in the ’70s.

Yeah, I’ve found myself writing songs that fit that particular band. Back when i was putting my first band together after the Flatlanders — or even going all the way back to the Flatlanders — I was finding I would write songs kind of depending on what instruments there were and what the rhythm was. And that kind of influenced the lyrics. So everything’s a part of everything else. Of course, you could take a set of lyrics and theoretically make a jazz tune out of it or a marching band song — you can pretty much take any set of lyrics and change it around a little bit. But when you’re used to working with one band, you start writing things that will work best for that band; especially rhythm parts. The bass is real important in just changing the whole feel of a song.

Since his passing, have you ever found yourself writing a song where you can’t help but hear Jesse Taylor playing it in your head? Almost like feeling a phantom limb?

Yeah. That happens, too. Sometimes a song just screams for what Jesse would play. Or David or whatever. So sometimes it’s a matter of just finding that spot and then just going for it. A lot of things you can’t change; of course you can’t bring anybody back that has already left this world, but sometimes you can bring their spirit back. That’s what’s so amazing about music; it’s not just a physical thing, but also a spiritual thing that happens in the present moment. It’s really powerful when you can kind of bring up the essence of someone like that. Anybody who has ever played with Jesse, there’s a certain spirit that is really … I don’t know what the word is, but the essence of that person comes through the essence of other people.

I’ve constantly been amazed over working for so long … basically my entire life ever since I was 8, I’ve been working with music, and been on the road you know 50 years. So I’ve kind of seen all different forms of music, and I’ve gone through all different phases and stages and cycles and everything else. But I feel really lucky to have gone through all those things. Because every time I’ve played with different people I would learn something else. And the same with songwriters. I’d go out and do those things with the Flatlanders, and then do things with the Four Horseman Tour with Lyle Lovett and Guy Clark and John Hiatt, and every time I’d get a little essence of a better way of approaching writing a song. It would kind of open up doors that might have been nailed shut years ago, and I’d open them back up and have a whole new lease on a different perspective on how to start a song or how to finish a song. So each part of it kind of leads up to the present day, and I’m always looking for another way to approach making something happen.

I mentioned your Letter to Laredo album a minute ago. You can hear some of the “essence” of that era on your latest album, Panhandle Rambler, on the tracks featuring [flamenco guitarist] Teye. It’s been a long time since you worked together. Have you stayed in touch with him all these years?

Yeah. In fact, two or three years ago we went out and played a few shows together. He’s not playing a whole lot; he’s building beautiful guitars that nobody can afford. But he’s always been a craftsman. I first ran into him back when I was kind of conceiving a record that kind of takes place on the Texas/Mexico border, and Teye happened to be at that spot at that time. And the Panhandle Rambler record kind of revisited that era, only with some new twists. There’s a whole different kind of a danger element out there now, like with the cartels and all on the border, so I kind of added that in to the Panhandle Rambler record.

It’s definitely changed a lot. I’m from El Paso, and it always seemed like a pretty dull place to grow up. But now you read about it or even hear it mentioned on like Breaking Bad, and it might as well be bordering Baghdad.

Yeah, I know. There’s been hundreds of people, maybe thousands killed right across the border there in the last 20 years. I remember a while back when Terry Allen had a wedding party in El Paso, and the main part of the party went over to Juarez after the dinner. And we kind of took over a bar there, and we wondered why there was not a soul in the place. It was right on the Avenue de Juarez, right through the middle of town, and it should have been packed — it was a Saturday night. But it was completely empty. So we kind of took it over, and we were there for a couple of hours and nobody came in. We asked the bartender, “What’s the matter? It’s Saturday night and nobody’s here.” And he told us about how there had been a killing a few weeks past that had killed dozens of people, and everybody was just staying in. I guess that was sometime in the ’90s, probably the late ’90s, and that was the first time that I realized we were living in a different world.

Y’all were just a bunch of dumb Texans who didn’t know better!

Yeah! We thought we had the whole place to ourselves, and actually we were probably lucky to get out of there alive.

It only came out last fall, but does Panhandle Rambler still feel new to you? Or is that already miles in your rearview?

You know, it’s still kinda new, because I’m still learning the songs! Sometimes I write the songs, and it takes me six months to learn ‘em. And my daughter just did a video for it. Her and her friends have a video company, and they did a video of one of the songs that’s going to be released at SXSW. It’s for “Don’t Roll Those Southern Eyes at Me.” I kinda gave them free reign to do anything they wanted to, and they got their friends together and … it’s real interesting to watch them put the whole thing together. I’m in it, but i’m not actually playing in it; I just have a little spot in it. They filmed most of it in Joshua Tree, California and downtown L.A.

For years and years, every time I’d get a chance to talk to you, I’d ask you when you were going to be finished with that “low-res” version of your long-lost Hi Res album. You finally put that out as B484 in 2014. And we also always talked about the novel you’d been working on forever, Reverb, which finally came out in 2014, too. So now that both of those projects are in the rear view, what’s been possessing you now?

Well, speaking of my daughter, I’ve got a record that I did for her as a Christmas present back when she was 2 or 3 years old. It’s basically a little lullaby album. I never released it because I just thought of it as a Christmas present. But I’ve got a lot of friends who are having kids, or their kids are having kids, and so I just thought … I’ve kind of passed it around over the years and just given it to friends who were bringing a new child into the world and wanted some songs to play. And then a lot of those people would come to me and say, “My kids like it, but a lot of the adults like it, too!” So I’m actually thinking about putting that out.

And I’ve got another record that is just about finished that I’ll probably put out in the fall. And I’ve got a spoken word record and also a spoken word version of the Reverb book that I’ve finished. So I’ve got five or six projects on the fire.

Typical.

Yeah, sounds about right!

Any idea what direction that new record will take?

I’m just recording songs and putting stuff together now, so I have no idea about that yet. I’m going to be working on it quite a bit this spring, so I’ll know more about it down the line. I don’t really set out doing a record thinking about what direction it’s going to go in; I basically just start out writing and then see as I write more songs, see which songs tell me which way to go. When we were doing the Flatlanders record, me and Butch were writing songs, and figured out that sometimes it’s really hard just to stay out of the way of the song. Sometimes you write a song and then you get in middle of it and start changing everything, and you screw it all up. So sometimes I have to just stay out of the way.

I didn’t get a chance to ask you about this back when Reverb came out, but given how so much of that was clearly based on your own experiences, how early in the writing process did you decide that you wanted to write it as fiction, instead of as a memoir?

Pretty soon. I’d probably written maybe a chapter or half a chapter, and I realized I could not write it as a biography or as something that had actually happened; I had to just take things that had happened and work around that. Because obviously you can’t tell dialog and remember everything from 30 years ago or something. And once I decided to do that, then all of a sudden I didn’t have to … everything didn’t have to be exactly right. The characters could be anybody. And that freed me up. I would have never been able to finish it if I hadn’t turned it into a fiction piece and been able to get in all different directions. That’s the only way I could have ever finished it.

The whole process of it was just an experiment anyway to see if I could do it. I never had a reason to do it, other than just wanting to tell the story of a certain perspective of the ’60s. Because it was a real interesting era, and it formed a lot of the way that I approached things from then on. And in all the interviews I’d ever done, I’d never told a certain side of the story about a lot of things that were true in it — like being busted on the very day that marijuana and psilocybin and mescaline all became illegal under Richard Nixon. They all became felonies. So things like that … I wanted to tell that story, because it kind of related to what’s still going on today, with kids getting thrown in jail for a little bit of pot. I know in my case they were looking at 20 years in Huntsville, and now there’s kids that are in jail that really shouldn’t be.

Speaking of policies and politics, how are you liking this year’s primary race?

[Laughs] Oh, man. It’s like Saturday Night Live seven nights a week for months and months on end. I’ve never seen anything quite so absurd as this election year. You couldn’t write an episode that was any more bizarre than what these last few months have been. I don’t know; I never thought I’d see how things unfolded like this year. So every day, I’m wondering what’s going to happen next.

What about the news that Obama’s going to be a keynote speaker at SXSW? You probably never thought you’d see something like that happen, either.

Oh is he coming? I think that’s wonderful. I have a feeling we’re going to miss Obama. As much as everybody has gotten on his case, I have a feeling we’re going to miss him when the new election year comes up. I’m just … Donald Trump has continually amazed me that he can stay on the forefront with all the lunatic things that he’s said. I really can’t believe it.

Did you see The Producers sketch that Jimmy Kimmel did with Nathan Lane and Matthew Broderick, where they pick Trump as the perfect candidate to fail in a money grabbing scheme and it all backfires?

[Laughs] No, I missed that. That’s really good.

You mentioned the Four Horsemen shows you used to do with Lyle Lovett, John Hiatt, and Guy Clark. Was there ever talk of doing a record together with those guys, back when Guy was in better health?

We had talked about that, but I guess the whole talk kind of veered off when Guy got to being where he couldn’t go out on the road anymore. And it was real hard for him to even get together to write songs, with me and Lyle living in Texas and John and Guy living in Nashville. Fortunately, we did record the whole show a couple of times. Lyle had all of his sound crew record three nights out in California. So maybe there’ll be a live record of it, and possibly a video, because they shot video on all that, too. But as far as sitting down and writing a new set of songs, I kind of doubt it. It would have been really be great to do that, though. I have the utmost admiration for all those guys, and they inspired me immensely.

And how about the Flatlanders? Anything coming up on that front?

Well, I actually think that we will do something, write some more stuff. I just don’t know when, because we’ve never had a schedule on when we would write a record — it’s always kind of come about with no reason whatsoever. That’s kind of the way we got together. But Butch and Jimmie came out for the Songwriters Hall of Fame thing and played a song with me that we wrote together, “Right Where I Belong.” And we kind of talked about getting together and putting a few songs together, so who knows. It’s been about three or four years [since the last record], and that’s been our time frame here lately. It’s a lot of fun to get all of us together and see which direction we go, because it’s never predictable.

You’ve got some dates coming up with Ruthie Foster and Paul Thorn. How did that come together?

It kind of started when the Flatlanders did a show up in Napa Valley, somewhere in Northern California, about three years ago, and we talked about going out and doing some more stuff, but we never could get it together with all the Flatlanders, all the details never worked out. But we ran into Ruthie Foster and thought, man that’d be great to have her — add kind of a blues element to the show. And we tried out a few shows last year to see how it would go, and it worked out pretty good, so now in the spring we’re going to do about 10 or so shows together. It’ll be a good time. I always enjoy going out and hearing other people’s songs when you’re on a stage together. It’s pretty intense.

Wrapping up here … You turned 69 in February. Is it catching up to you yet, or for the most part do you still feel loaded for bear?

Well, I had a little bad thing happen a couple of weeks ago, but I’m actually doing really good now. I’ve got a good tour schedule coming up, and — oh yeah, Sharon [Ely’s wife] just reminded me to mention that I’m doing a Prairie Home Companion deal with Garrison Keillor coming up in April. I’ve been on that show a number of times over the years, and Garrison’s about to move on so I’m going to do it one more time with him when they come down to do a taping in Austin. So there’s that and the shows with Paul and Ruthie and some other stuff, and of course I’m always working on new songs. So I’m thrilled that I’m this age and still able to make music. I never, ever expected that when I was growing up.

You’re still young! Give yourself another five years, and you can run for president, like Bernie.

[Laughs] Yeah, that Bernie Sanders … he’s a piece of work, man! He reminds me kind of the Flatlanders back in the ’70s. He’s got kind of the same ideas and the same kind of … I don’t know. He’s got that idealistic look into the future, and he’s a really smart guy, but I just don’t think that he would be elected. It’d be of like having Butch Hancock being elected governor of Texas. Kind of far out.

Well, Kinky Friedman gave it a run.

Yeah, Kinky! Is Kinky running for anything this year? That’s always fun.

I think he’s just running to his humidor these days.

Ha!

I want to close on a philosophical note. In the tribute video that was put together for your TXHSA Hall of Fame induction, at one point David McLarty referred to the Flatlanders as “a box of chocolates.” You never know what you’re getting with those, so if you’ll indulge me, what variety of chocolate would each of you be? Between you, Butch, and Jimmie, who’s packing nuts and who’s filled with that weird fruity nugget?

[Laughs] Boy howdy, that’s … wow. You know, I’d say … boy, that’s difficult. That’s too deep for me! I can’t picture the Flatlanders as a box of chocolates myself.

Are you guys more of a salty snack?

I would say that it was more kind of a vegetarian goulash.

Great article Richard!