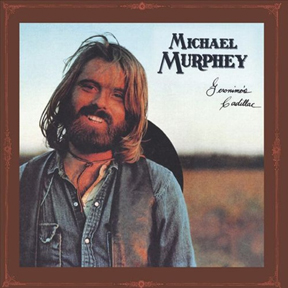

MICHAEL MURPHEY

Geronimo’s Cadillac

A&M Records

One of the greatest legends of Texas music isn’t a specific artist or band so much as it is a movement: the “Cosmic Cowboy” days of the 1970s, with its gravitational center in funkier-than-thou, cheaper-than-now Austin. More or less interchangeable with the “Outlaw Country” label that subsequent generations still aspire to carry on, it wove the adventurous spirit of hippie-friendly rock ’n’ roll into the rootsy sounds of country music and the enduring mythology of the American West. The magnetic pull of it shook burned-out drifter Jerry Jeff Walker (formerly Ron Crosby) out of his post-“Mr. Bojangles” Key West haze, boomeranged a successful but disillusioned songwriter named Willie Nelson back home from Nashville, and just as significantly — although his legacy hasn’t gotten as much ink in recent years — spurred a lonesome L.A. cowboy named Michael Murphey to get back to his Texas roots and make the most ambitious music of what would be a multifaceted and fairly fascinating career.

Younger listeners might think of Murphey, if they’re familiar with him at all, as the guy with the unwavering commitment to the niche of traditional-minded Western cowboy music since around 1990. Slightly older ones might remember his easygoing mainstream country hits from the ’80s (he edged out George Strait for the Academy of Country Music’s Best New Male Vocalist in 1982), and just about everyone has likely heard his 1975 crossover hit “Wildfire.” But even before that, Murphey had been something of a mover and shaker, finding his footing as a youngster playing Texas folk clubs with folks whose path he’d cross again like Steven Fromholz and Ray Wylie Hubbard. Shortly thereafter he’d followed Michael Nesmith — a buddy and sometime bandmate — to Los Angeles; when Nesmith lucked into a membership with the TV show/band project the Monkees, Murphey’s song “What Am I Doing Hangin’ Round?” popped up on their successful fourth album. Big acts of the day like Bobbie Gentry and Flatt & Scruggs cut the young Texan’s tunes too, and Kenny Rogers recorded a whole album’s worth of Murphey songs (The Ballad of Calico) somewhere along his own path between pop and country music. Murphy also co-fronted a short-lived band called the Lewis & Clarke Expedition, but his career as a performer had yet to catch up to his progress as a songwriter.

But then, in a couple of watershed years, Michael Murphey moved back to Texas, doubled down on the threads of Western mythos running through his music, caught the ear of legendary producer Bob Johnston and took a break from his busy Lone Star State gig schedule to record his proper debut: 1972’s Geronimo’s Cadillac. All at once, it was a culmination of years of behind-the-scenes creative striving and a stunning, fully-realized debut from a shaggily handsome kid who suddenly jumped to the forefront of a whole new subgenre that was taking over the state and echoing across the country one beer-soaked, grass-smoke-tinged gig at a time.

First off, there’s that title track. Much like Clint Eastwood and others did on film around the same time, Murphey wasn’t afraid to ask some hard questions about American progress and treatment of the marginalized. Whatever poetic license led him to plumb the metaphors in the U.S. government’s conciliatory gesture of gifting the defeated Apache chief with a luxury car was indelibly matched by the soaring, wide-open harmonies and acoustic country-rock framing the rangy, gritty tenor of his youth. “They took his land and they won’t give it back/Gave Geronimo a Cadillac,” he wailed, somewhere between angry and bemused and heartbroken. The memorable breakdowns towards the end of the song — thumping guitar licks suggesting some kind of tribal rhythm — might have raised some PC eyebrows nowadays, but the song was hailed by Native American activists in its heyday and remains one of the most beloved anthems of the whole “progressive country” era. Even to the historically disinclined, “Geronimo’s Cadillac” was the most distinctive tune on an album full of rustic yet ambitious killers, and a calling card for not only an exciting new artist but a whole scene of recklessly intelligent musicians.

The rest of the album is pretty low on anger, political or otherwise, and overall it was more in tune with the mellow, earthy, then-recent folk rock of folks like The Band or the Grateful Dead than Murphey’s more country-rooted contemporaries like, say, Waylon Jennings or Billy Joe Shaver. Like many a fine album, it’s sonically varied and cohesive all at once, sticking to a vision but ingeniously changing up the angles. There’s bluesy, barbed-wire guitars on “Natchez Trace” and piano balladry on “Calico Silver,” and they both stand as evidence of Murphey’s knack for giving his songs a sense of history and geography. Occasionally the tempo kicks up — the gospel-fired “Harbor For My Soul” or the guitar-driven dynamics of “Crackup in Las Cruces,” for example — but even on the unhurried likes of “Waking Up” or “Boy From the Country,” the impassioned focus of Murphey’s vocals lend an intensity that kicks it all a gear higher than the easy-listening/folk hybrids that were coming into fashion around the time. Even his revisit of “What Am I Doing Hangin’ Round,” pleasant enough in the hands of the Monkees several years prior, takes on a lonesome life of its own amidst the chugging jangle of the acoustic guitars.

On Geronimo’s Cadillac, Murphey sounds like a man who could scarcely wait one more day to commit his own songs to record, singing his first round of solo material as if it were his last. He would show some career flexibility in the decades to come — even modifying his name to “Michael Martin Murphey” to avoid confusion with a well-known actor when his career drifted back to Hollywood — but the singular commitment to what was becoming a whole new genre around 1972 is still breathtaking to hear. Back then, the man best known nowadays for his old-school cowboy records was a new kind of cowboy, riding ahead of the herd on a whole new plain. — MIKE ETHAN MESSICK

No Comment