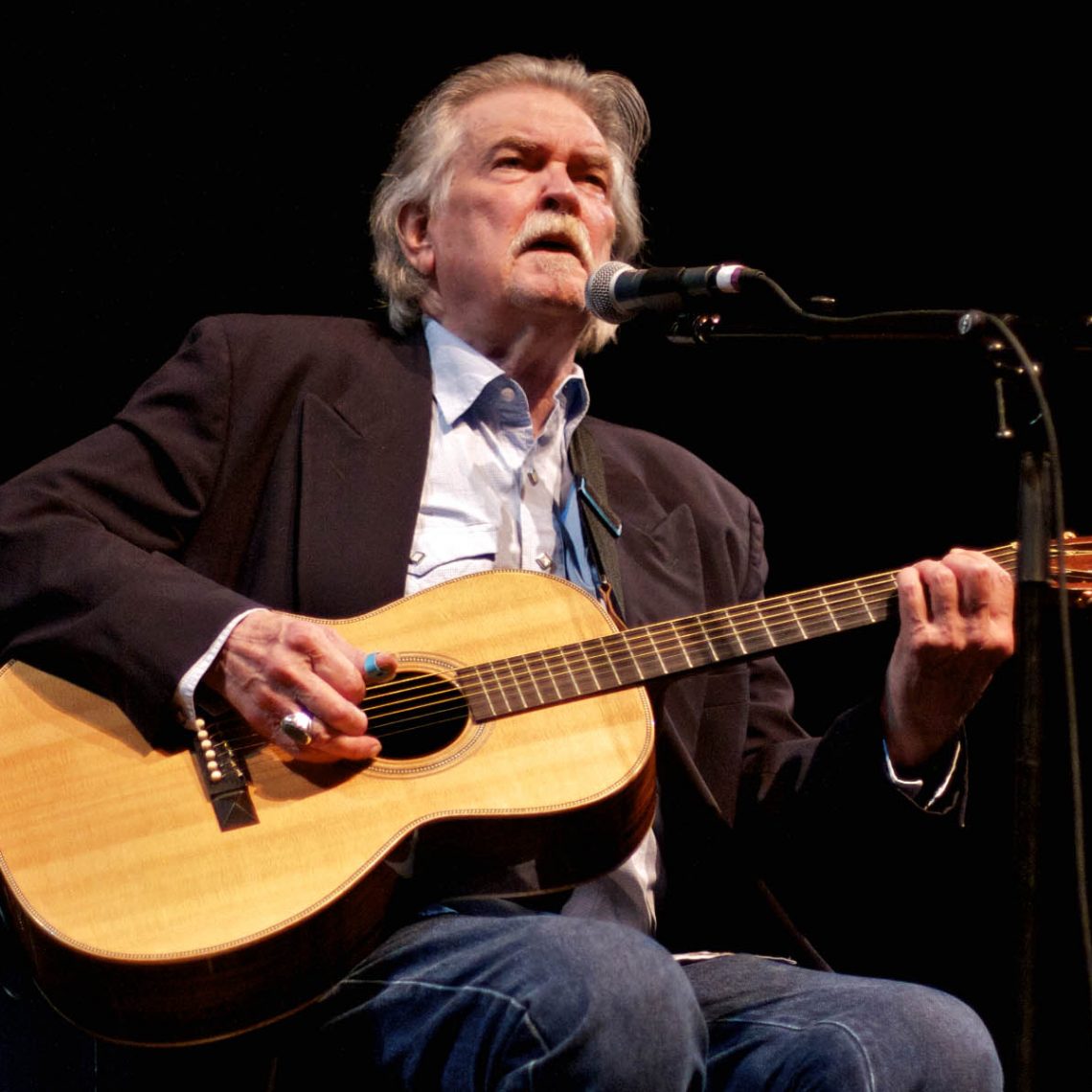

IBy Richard Skanse

Guy Clark, the dean of Texas songwriters, passed away early Tuesday morning in Nashville. He was 74. The legendary troubadour, who won his first Grammy (for Best Folk Album) for his last album, 2013’s My Favorite Picture of You, had been in failing health for months and had retired from active touring and performing not long after the 2012 death of his beloved wife Susanna (a painter and fellow songwriter herself).

Clark, who was born in the West Texas town of Monahans in 1941 but came of age on the Gulf Coast and in Houston, is survived by his son Travis from a previous marriage, two grandchildren, his sisters Caroline Clark Dugan and Jan Clark, and a lifetime’s worth of some of the finest songs ever written in Texas or Nashville, which he called home for more than four decades.

A handful of those songs preceded Clark himself into Texas legend. By the time Clark released his debut album in 1975, Jerry Jeff Walker — who Clark first crossed paths with on the Houston folk scene in the ’60s — had already made instant progressive country classics out of “That Old Time Feeling,” “L.A. Freeway,” “Desperados Waiting for a Train” and “Like a Coat From the Cold.” That made Clark’s own Old No. 1 — which featured his own versions of each of those songs along with such other benchmarks as “Texas, 1947,” “Rita Ballou” and “She Ain’t Going Nowhere” — a veritable “best of” collection in all but name. “She Ain’t Going Nowhere,” in fact, was the song Clark would often name — when pressed, if only to get past the topic — as his personal favorite. “Just because it was so cleanly written, so succinct and on the money to me,” he said in a 2006 interview. “It still is.”

But the words “cleanly written, so succinct and on the money” could just as easily be used to describe any song in the Clark cannon — from “Step Inside This House” (the very first song he ever wrote, which went unrecorded until Lyle Lovett rescued it from obscurity in 1998) to “My Favorite Picture of You,” the title track to his last album. (Jerry Jeff actually beat him to that one, too, recording the first version of it on 2011’s This One’s For Him: A Tribute to Guy Clark, the Americana Music Association “Album of the Year” winning multi-artist salute co-produced by Clark’s biographer, Tamara Saviano.) Clark himself didn’t record especially prolifically — he recorded just 13 studio albums over the span of 38 years — but his exacting standards made for a body of work that was comprised almost entirely of “keepers.” As impressive as the list of artists featured on This One’s For Him was (a veritable who’s who of Americana and Texas music all-stars, including Lovett, Willie Nelson, Joe Ely, Terry Allen, Kris Kristofferson, Rodney Crowell, Steve Earle, Robert Earl Keen, and many more), it was the track list alone that really said the most about Clark’s legacy: from signature favorites like “Dublin Blues,” “The Cape,” “Texas Cooking,” “Old Friends,” “Homegrown Tomatoes,” “The Randall Knife,” and “Stuff That Works” to even such later day gems as “The Dark,” “Hemingway’s Whiskey” and “The Guitar.”

The exquisite attention to detail implicit in every one of those songs — each word weighed, measured, and justified before being fitted into perfect place with a watchmaker’s precision — earned Clark the oft-overused handle of “Craftsman.” He wasn’t overly fond of the title, acknowledging in the aforementioned interview that while “there’s a certain amount of that [craftsmanship] in there,” there was also something about the word that implied, however unintentionally, that his writing was “by rote, instead of inspired. That it’s just … crafty.”

But nobody familiar with his songs — let alone the “craft” of songwriting in general — could have ever truly felt that way about his art. Clark may have famously written his songs down on graphing paper and fine tuned every phrase and melody with the same patient care that he put into the guitars he built and repaired his entire adult life, but the end result was never less than pure poetry, as deep and meaningful as any of the songs written by his infamous running buddy and friendly rival, Townes Van Zandt.

The key difference between the two, though, was that Clark’s songs never shrouded themselves in layers of mystery and metaphorical obfuscation. They were built to work, not to study and decode. But study them all songwriters should, and will, because that’s the kind of stuff you reach for when you aspire to write something real — and lasting.

No Comment