Editor’s Note: In honor of the great but often under-sung, Houston-born singer-songwriter David Rodriguez, who passed away in the Netherlands a year ago this week, LoneStarMusicMagazine.com is proud to feature this appreciation by Tarleton State University professor Craig Clifford, co-editor (with Craig D. Hillis) of the new book, Pickers & Poets: The Ruthlessly Poetic Singer-Songwriters of Texas (Texas A&M University Press). Clifford’s eulogy for Rodriguez is adapted from his book chapter, “Too Weird for Kerrville, the Darker Side of Texas Music.” The essay originally appeared in Langdon Review of the Arts in Texas, Vol. 5 (2008-2009)

Editor’s Note: In honor of the great but often under-sung, Houston-born singer-songwriter David Rodriguez, who passed away in the Netherlands a year ago this week, LoneStarMusicMagazine.com is proud to feature this appreciation by Tarleton State University professor Craig Clifford, co-editor (with Craig D. Hillis) of the new book, Pickers & Poets: The Ruthlessly Poetic Singer-Songwriters of Texas (Texas A&M University Press). Clifford’s eulogy for Rodriguez is adapted from his book chapter, “Too Weird for Kerrville, the Darker Side of Texas Music.” The essay originally appeared in Langdon Review of the Arts in Texas, Vol. 5 (2008-2009)

David Rodriguez: Too Weird for Kerrville

By Craig Clifford

As David Rodriguez recounted it to me, Townes Van Zandt was banned for several years from the Kerrville Folk Festival because his music wasn’t “family entertainment.” And when Blaze Foley punched out Rod Kennedy at Emma Joe’s (or got punched out by Rod Kennedy for spitting on him, depending on which version of the story you trust), he too was given the Kerrville boot. According to Rodriguez, a group of Kerrville outcasts and their spiritual brethren started gathering at Taco Flats in Austin each year during the Kerrville Folk Festival to play their brand of Texas music. They called their festival “Too Weird for Kerrville.”

Exactly who was or wasn’t banned from Kerrville and what the reasons might have been I won’t try to pin down, but it certainly tells you something about the attitude of the person telling this story. David Rodriguez was too weird for Kerrville, and perhaps even too weird for his native Texas — there’s a negative to that, but there’s a positive as well.

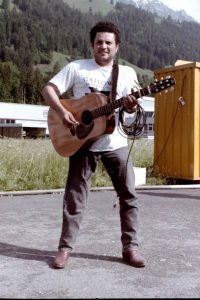

David Rodriguez died on Monday, October 26, 2015 in the Netherlands at the age of 63. Since I first met him in 1969, when we swapped sets in Austin coffeehouses, he was part friend and part nemesis. He was a charismatic personality with an endearingly mischievous smile that I am reminded of every time I see a photograph of his daughter, Carrie Rodriguez. He was also incredibly difficult to deal with at times. Because of that he sometimes sabotaged himself, burned his bridges, and alienated even his admirers. But he was a brilliant songwriter whose best songs stand alongside the best songs of Townes Van Zandt, Guy Clark, and the other great Texas folksingers who came of age in the coffeehouses of Austin and Houston in the late 1960s and early 1970s. Like the music of Townes Van Zandt, Rodriguez’s music is ruthlessly poetic in a way that is almost frightening to popular and commercial sensibilities. Unlike contemporary I-love-my-truck country, Rodriguez’s music takes us to places we’re not necessarily comfortable with.

David Rodriguez once wrote to me that Townes Van Zandt was a brilliant poet and, like Dylan, he copied or drew from the forms and language usage of old ballads from the British Isles and Ireland. It’s as though we were on a common path because I had grown up reading English poets from Sir Walter Scott to Dylan Thomas. So when I came into contact with guys like Townes (because there were others as well) it was like a homecoming.

Guy Clark and Townes Van Zandt supposedly would listen to recordings of Dylan Thomas reading his poetry and remark on how their lyrics paled by comparison. Like Clark and Van Zandt, Rodriguez was driven, even cursed, by the desire for the perfect song, and he judged his lyrics against the greatest poetry. He was too weird for Kerrville, not because he wanted to be a rebel, but because he was devoted first and foremost to his muse.

Like Van Zandt, Rodriguez was also steeped in the folk music of the British Isles, an interest that he developed in high school through his friendship with several girls from southeast Houston whose parents listened to the Weavers, the Kingston Trio, and Pete Seeger. In a 2008 email, he made these comments:

But the funny thing is the influence all those people had on my life. I mean where we grew up was certainly no “Meyerland.” It was a mix of just about everything you could imagine except black and brown. My family was the exception until around 1961, then one other Mexican family moved into the vicinity. And that was it. I remember when it happened because it was like someone putting a mirror to your face. Before then I really didn’t think of myself as different.

It was an unusual circumstance where I grew up. But all at once, about the age of sixteen, I fell into a circle of people, including Elizabeth Alpert, who turned me on to culture, liberal, beat American style. It was really through them that I got introduced into the Houston folk circuit finally ending up with meeting Townes and Guy Clark and a whole of bunch of other unnamed, unknown but equally important people to that scene.

In high school Rodriguez was a member of a folk club called the Wayfarers. When I met him in college, he was playing songs like “I Loved a Lass (She’s Gone to Be Wed to Another)” and “Rosemary Lane.” His finger-picking guitar on those songs — flat pick and two finger picks on his third and fourth fingers — was unequaled by any of the folk guitarists of that generation. Rodriguez’s contrapuntal guitar on “Rosemary Lane” made Bert Jansch’s version sound uninspired. When I met my future wife during my junior year in college, it turned out that she was one of those southeast Houston girls who had turned Rodriguez toward folk music, something of an irony for me since he introduced me to folk music when I met him during my freshman year of college.

***

When Lucinda Williams performed in Amsterdam in 2003, she remarked on David Rodriguez’s presence in the audience by saying: “I feel like I’m in the presence of genius because my friend David is here. Do you know him?” In an Austin poll conducted by Third Coast Music, David Rodriguez was voted best Texas songwriter for three consecutive years, 1992, 1993, and 1994. Lyle Lovett recorded Rodriguez’s “Ballad of the Snow Leopard and the Tanqueray Cowboy” for his tribute to fellow Texas songwriters, Step Inside This House. But much of Rodriguez’s music, outside of certain circles in Austin and Houston, has never made it onto the popular Texas or American music scene, and in 1994 Rodriguez abandoned his native Texas soil for good, heading off to Europe in the time-honored tradition of American expatriate artists looking for a home for their poetic spirits.

Stories abound about why Rodriguez never returned to his native country, most of them explaining why he couldn’t come back for various nefarious reasons. On the occasion of his death, however, what I think we should reflect on is the best part of him, the part that most defined him, his ruthlessly poetic music.

Rodriguez’s commentary on Texas — cultural, political, and poetic — is not of the warm and fuzzy variety, and it was inevitable that it would ruffle feathers. In part because of his Hispanic heritage and in part because of the bright light his mind seemed to shine on everything it came in contact with, his relationship to Texas was powerfully ambivalent. His music ranges from romantic lyricism steeped in the Texas of his youth to moving but profoundly disturbing indictments of social injustice, often in the same song. “The Other Texas” starts with a romantic encomium to his homeland:

She’s got lowlands just like Holland

She’s got mountains just like Spain

And all the sunshine of the summer

Western winds and eastern rain

Then it turns to “the other Texas”:

But drive your rent car across my hometown

To the streets the map don’t show

And you’ll see children with no future

That’s the Texas that I know

David Rodriguez songs are often overtly political. In fact, he spent a number of years as a political activist lawyer in Austin. He told me a few years ago that I should be careful about mentioning his name in certain circles in Austin because he still had enemies because of his activism. Whether that’s true or not, it tells you something about how Rodriguez understood himself. Occasionally his music crosses over from a poetic vision of things political to preachy political accusation, sometimes telling us what we’ve done wrong rather than getting us to see it by way of the seductive story or perfect turn of phrase. My relation to his songs as a performer has brought that home to me. Some of his songs I can’t see myself singing at all, like “Ballad of the Western Colonies,” a bit too much of a sermon for my taste: “As if it was something to be proud of, all the killing the cowboy done / How the boundaries were shaped with the barrel of a gun.” And some of his songs, like “The Third World” and “The True Cross,” I’ll put aside for being too much in the white-man-bad vein, then come back to them a few years later because the perspective they present, whether I “agree” with it or not, is so compelling.

This ambivalence in Rodriguez’s poetic mind resulted for the most part, not in political propaganda, but in art that forces us to rethink the way we look at ourselves and our place. Not unlike Faulkner’s relation to the South, loving it and hating it, Rodriguez’s relation to Texas was a beautiful but unsettling challenge. Rodriguez’s lyrics are the musical equivalent of what writers like Rolando Hinojosa have done in literature. They may in the end move us to action, but only because they get us to see things from a perspective that we would not ordinarily have.

But it’s important to note that Rodriguez’s perspective challenges but simultaneously strengthens our identity. Although Rodriguez left the United States in 1994 to live in the Netherlands, he never abandoned his Texas identity. Some of the political finger pointing makes an old gringo like me uneasy, occasionally even angry. Still I continue to find his music attractive because it talks about the same Texas that he and I grew up in during the 1950s and 1960s in Houston. His “Ballad of the Snow Leopard” (the title comes from the fact that he proposed to his first wife in front of the snow leopard cage at the Houston Zoo) is so rich in the images of my own childhood, of our own childhood, that the Hispanic and Anglo differences fade away in the vivid poetry of our “native borderland.” His music indicts the powerful and extols the powerless, but at the same time it unifies us in our humanness — or at least in our Texan-ness.

On A Winter Moon, his 2007 live CD done in Dordrecht in the Netherlands, Rodriguez brought back one of his most personal songs about his roots in Houston and Mexico, his family history, and his father’s death — “Hurricane.” To be sure, it includes a satiric condemnation of the unpoetic lives that most of us live:

And whatever it was they told him was worth this rat race

To this day I’m still not sure I understand

Except to keep your woman happy and the children all in school

And pay the doctor bills and pay the light bill too

In fact, it’s probably that kind of in-your-face condemnation that keeps Rodriguez’s music from “making it big.” But this song also evokes a passionate sense of place — and I recognize it as my place. I identify with this song as much as with any song ever written about Texas. The end of the song recounts the burial of his father:

And we laid him low in the same old southern grasslands

In his very own piece of this Texas coastal plain

Where you can almost smell the ocean

It’s just twenty miles away

I said, “You’ll like it here.”

And I could hear him sayin’

When the south wind blows in from the Gulf of Mexico

It makes me think about long ago, up on the bayou again

Son, you’d do well to live right and watch those ladies at midnight

When they start comin’ on like a hurricane

The only Texas burial scene I can think of with as much poetic power is the one at the end of Larry McMurtry’s Horseman, Pass By.

Racing Aimless, released almost two decades since Rodriguez had last set foot on Texas soil, leads off with a haunting elegy to his homeland, “Gulf Coast Plain”:

I was born on a Gulf Coast plain,

You can smell the saltwater in the rain

Land of the willow and the slow movin’ bayou

And the hurricane

And the album closes with an unedited version of “Yellow Rose of Texas.”

***

We can lament the fact that more of Rodriguez’s music hasn’t made it into the mainstream, that it hasn’t been given a wider and more popular recognition, that far lesser talents are the ones that tend to make it big. Or we can appreciate the sheer beauty of the songs and give thanks for the pathos and healing catharsis that Rodriguez’s ruthlessly poetic music offers to those who choose to listen.

David Rodriguez wasn’t cut out to be wildly popular — he had a more pressing calling. He made his choices from early on, and he stuck to those choices and paid prices for them. But I never saw any regret in him, and whatever mistakes he may have made in his life, he goes to his grave with his poetic integrity intact. That single-mindedness of purpose is a bit frightening to the rest of us — and certainly it can be a destructive force for those who get in its way — but what would life be without the poetry that comes out of it?

As I wonder whether David Rodriguez will be laid low in the Netherlands or in “his very own piece of this Texas coastal plain,” I think of the lines from Yeats that Larry McMurtry put to such good use: “Cast a cold eye / On life, on death. / Horseman, pass by!” Rest in peace, amigo.

“REQUIRED READING” ––

I am honored to be a part of this project. I’m proud of The Craigs (Clifford & Hillis) for their commitment to this project, as well as their ability to herd music writers through the process. Poets and Pickers is a Texas songwriting primer – required reading for every songwriter and Texas music aficionado.

I was at Emma Joe’s during that incident sitting with Rod Kennedy

Blaze was drunk and bad mouthing Rod and even me. Blaze then stood up from his table at least 20′ away and spit a large glob across the room aimed at Rod. Rod flew over there and the altercation began. Emmas had one employee who was reluctant to get involved . Several patrins separated them, lucky for Blaze.

Blaze was an obnoxious drunk.

Thanks for referencing the song, “The Other Texas,” by David Rodriguez. The track is from the album PROUD HEART, and was released in the U.S. by our label, Recovery Recordings in Houston, Texas, in 2006. Needless to say, it is still available in digital format and on CD, online, and where finer CDs, tapes and LPs are sold.