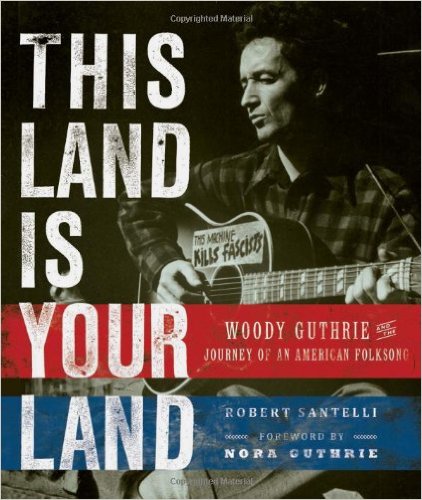

This Land Is Your Land: Woody Guthrie and the Journey of an American Folk Song

This Land Is Your Land: Woody Guthrie and the Journey of an American Folk Song

By Robert Santelli

Running Press

By Lynne Margolis

(May/June 2012/vol. 5 – Issue 3)

There’s barely a school kid alive who doesn’t know the words to “This Land is Your Land,” one of this nation’s most beloved, pride-inducing anthems. But if Woody Guthrie had popularized the song the way he originally wrote it, it’s a good bet that generations of voices would never have lifted together in spirited praise of redwood forests, gulfstream waters, golden valleys and diamond deserts.

The verses he cut off were his peeved response to Irving Berlin’s “God Bless America,” and they read:

As I was walkin’ — I saw a sign there

And that sign said — no trespassin’

But on the other side … it didn’t say nothin!

Now that side was made for you and me!

In the squares of the city — In the shadow of the steeple

Near the relief office — I see my people

And some are grumblin’ and some are wonderin’

If this land’s still made for you and me.

Regardless of which way one perceives the song — as a loving ode to our wonderful democracy or a communist sympathizer’s protest of the have-vs.-have-not status quo — it still has the capacity to move us, nearly 75 years after Guthrie first penned it.

That’s why Robert Santelli’s This Land Is Your Land: Woody Guthrie and the Journey of an American Folk Song, is a worthwhile read, not just for Guthrie students, but for anyone seeking insight into our current socio-political environment. Especially now, as we come scarily close to mirroring the days when Woody’s writings would have gotten him called before the House Un-American Activities Committee, had he not already started suffering the ravages of Huntington’s disease.

An historian and educator at heart, few people are better suited to spread the gospel of Guthrie than Santelli, who, as a teen, fell in love with the father of folk the way many do: via Bob Dylan. Later, he helped Woody’s daughter, Nora, establish the Woody Guthrie Archives before joining Cleveland’s Rock and Roll Hall of Fame & Museum, then becoming executive director of Seattle’s Experience Music Project and now, Los Angeles’ Grammy Museum.

Interviewed during South By Southwest, where he moderated a “Woody at 100” panel and co-hosted a centennial showcase, Santelli observed, “This country was founded on the music of social change. All you have to do is go back to the American Revolution and read about how young radicals wrote what were called broadsides — basically lyrics set to English beer-drinking songs — and sold those lyrics on street corners; they were very radicalized, pro-American, pro-revolutionary lyrics, and that helped sway public opinion during the American Revolution. So music has certainly played a role in the direction this country has taken from its origins.”

Guthrie may not have fathered the concept of using music to incite change. But it wasn’t until he began traveling the country, writing and singing songs about the disenfranchised, the mistreated and the underclasses, until he expanded his audience via radio and began selling albums as one of the Almanac Singers, that what we now consider folk music became known as a popular genre.

Though Santelli occasionally indulges in bits of dramatic license and could have used stronger editing (most grievous typo: Soul Asylum’s Dave Pirner referenced as Dave Primer), he engagingly turns the story of Guthrie’s song into a thorough examination of 20th-century American history. And despite his claim that the book is not a biography, it serves as a well-documented look at Guthrie’s life — and doesn’t shy away from noting flaws such as his womanizing and disregard for hygiene.

Nora Guthrie provides a wonderfully personal forward — including the revelation that, like most of us, she first learned the song via an elementary school songbook.

Thanks to Pete Seeger and latter-day troubadours from John Mellencamp to Jimmy LaFave, Ellis Paul and Tom Morello, many of us are finally familiar with all the verses. But even in its abbreviated form, it’s still one of America’s greatest songs. That’s the beauty of folk music: it’s meant to morph, to change as the times change — or need to.

No Comment